A long time ago, I thought Paul Heyman's Extreme Championship Wrestling was cutting-edge. Or, to be more precise, I thought it was wrestling that involved a lot of cutting with edged implements, much like the action I’d grown up with in the American South (Jim Crockett Promotions' Starrcade '85, for example, saw wrestlers bleeding in nearly every single match on the card... and manager J.J. Dillon somehow got it twice). However, I never viewed the ECW as must-see TV, because even back then, I recognized that the matches suffered from a dearth of storytelling and that most of the performers were little more than untrained, jorts-clad stuntmen seeking to hit as many high spots as possible.

A list of botched maneuvers and nausea-inducing razorblade jobs from the promotion's pay-per-views and house shows could fill thousands of pages. Nevertheless, it was this ECW "hardcore" style, adopted by Vince McMahon's WWE in an attempt to win the ratings war against WCW, that came to characterize the sport's Attitude Era. And it was the story of Tommy Dreamer (Tom Laughlin) that best exemplified what the ECW was all about: taking your pain like a man.

"We don't have those pretty blue mats around the ring," ECW announcer Joey Styles would frequently tell viewers, reminding them that his federation's wrestlers-cum-masochists weren't receiving the slightest bit of relief from their agonies. The old rule in wrestling had been to make the punishment look real while reducing its impact as much as possible; the ECW approach was to have the performers look as ridiculous as possible while performing moves that could only hurt themselves (quick question: if you were fighting someone, would you use a moonsault or a shooting-star press to defeat them?). The wrestlers might not know a wrist-lock from a wristwatch, but man, these guys could really fall on their asses.

Previously, having a great bleeder like Dusty Rhodes "gig" his forehead with a small piece of a safety razor was sufficient to sell a match to the fans. It looked good on account of the copious amounts of blood that the performer would spill, but it was still relatively safe (emphasis on relatively; the scores of men who contracted Hepatitis C during the 1960s and '70s might beg to differ). Now, however, "getting color" was just an apéritif. Unforgiving Philly and New Jersey fans would boo the wrestlers out of the building if the main event didn't involve dozens of pratfalls and neck-breaking tumbles. In fact, even if the main event did involve those things, but they were performed poorly, the raucous ECW crowds would treat the wrestlers to a chorus of "You fucked up!" and "Boring!" chants.

Tommy Dreamer, who’d been trained by longtime WWE jobber-to-the-stars Johnny Rodz, entered ECW working a naive babyface gimmick. He wore green wrestling tights with suspenders and possessed, at least by the standards of other ECW workers, a well-maintained physique. Although he feuded with various bad guys during his time in the promotion, Dreamer's overall story arc remained consistent: to gain the respect of the bloodthirsty fans, he was willing to absorb massive amounts of punishment.

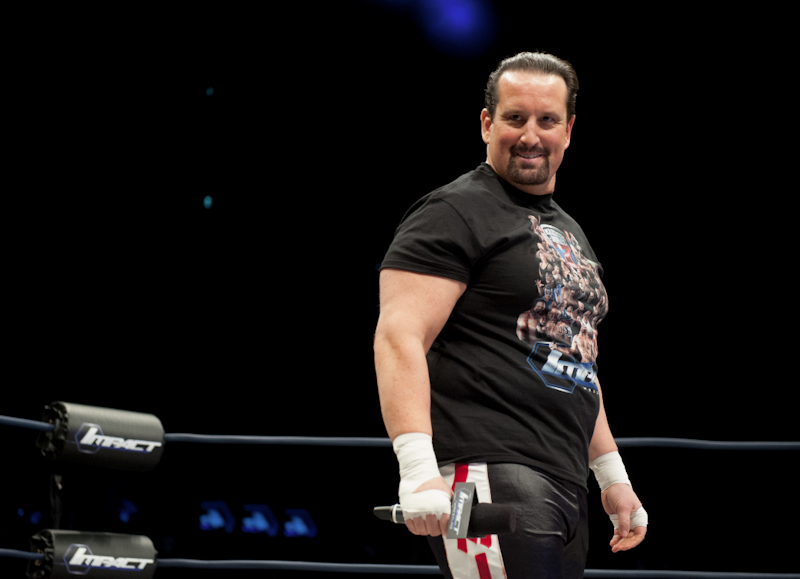

Until the ECW's bitter end, Dreamer's role consisted of losing violent matches to top opponents. He was brutalized with a "Singapore Cane" during a career-making bout against beer-drinking kick-and-punch specialist Sandman (Jim Fullington), and endured beating after beating from his "kayfabe" arch-rival Raven (Scott Levy). By the time the federation closed, he was a minor legend, a bump-taker and bleeder so respected that he managed to parlay his eight years in that promotion into another decade of midcard work in TNA and WWE.

I was only a sporadic viewer of ECW programming, both because it wasn't easily accessible in Raleigh, NC, and was usually pretty hard to watch. But the sight of Dreamer taking those cane shots "hardway" from the Sandman and pleading, apropos Kevin Bacon exclaiming “Thank you, sir, may I have another?” in Animal House... that I saw, and that stuck with me. When, I wonder, did Dreamer realize that this was what it would take to make it to the top?

"Hardcore Legend" Mick Foley's first book, the eminently readable Have a Nice Day!, offers a glimpse into the mind of a competent athlete (in Foley’s case, a lacrosse goalie who was pursued by a number of Division I schools) who realized that his athletic skills would only carry him so far. For Foley, the wrestling equivalent of snuff pornography would punch his ticket to the big time. Over the course of five memoirs, he grapples with the consequences of this approach, with the toll exacted on his body, and with a desire to discourage other would-be Dude Loves from leaping off their rooftops while simultaneously finding plenty of opportunities to praise his own body-mutilating work.

Foley's ambivalence is understandable. Even after decades of trying to disentangle masculinity and violence—after decades of top-down, educator-approved socialization that condemns physical violence and urges a "safety first" approach under all circumstances—a certain subset of hyper-masculine men continue to take inordinate pleasure in their scars. Absorbing damage may not be preferable to dishing it out, but "taking it like a man" serves notice to other men that even if you happen to be someone worth trifling with, you're not someone who would ever cower in fear.

I've endured my fair share of mental and physical beatings. And I'll admit, there's something intoxicating about taking the beating of a lifetime. In a certain sense, surviving one of these is preferable to dealing with the thousand annoying micro-aggressions that comprise a single day. The beating itself is dramatic and initially quite painful, but as Mick Foley notes in his discussion of his classic death matches with Terry Funk, once the numbness and adrenaline kick in, the next few steps are surprisingly easy. For a while, you're operating solely on instinct, which means that all conscious, chronic stresses have been banished from the mind, and for a few days or weeks after that, you're focusing on recovering and "rebuilding." You have a temporary plan of action, a fleeting sense of purpose, and when it's all said and done, you'll even have a war story to share with others.

Yet in a curious way, craving the beating of a lifetime is sort of cowardly. Absorbing punishment to prove you're a man, which was how Tommy Dreamer won the hearts and minds of the ECW faithful, seems the easy way out. While it's undeniably heroic to be martyred in the service of advancing a legitimate cause, actually seeking out martyrdom for its own sake, as was the case with some enthusiastic early Christians in the waning days of the Roman Empire, might be a less courageous act than merely dealing with your problems as they arise.

I'm not saying it isn't "manly," at least in one woefully outdated sense of that term, to withstand ultra-violence. I wouldn't want to eat a bunch of cane shots from a reckless opponent who was by many accounts inebriated a good percentage of the time. But perhaps the Tommy Dreamer narrative could've been constructed differently: perhaps he could've "gotten over" with the fans by means of exciting interviews, psychologically riveting but safe wrestling, and careful packaging and promotion on the part of Paul Heyman. It wouldn't have been as visceral, but it might’ve left him feeling more fulfilled, much as how learning to tolerate life's vicissitudes with equanimity rather than via violent outbursts improves the lives of those who cultivate that skill. Dreamer would assuredly be walking around a little better than he does right now, at any rate.