Sitting in a Manhattan diner one morning, a cold winter wind whipped its way around an empty street corner. Trash and papers jump the curb. Sipping a cup of coffee, the temporary absence of people captured a lonely feeling. Unfolding memories evoke a sense of calmness. Even though it’s early in the day, the setting suggests Edward Hopper’s sublime masterwork Nighthawks. For those unfamiliar with the painting, it’s a penetrating reflection on modern isolation.

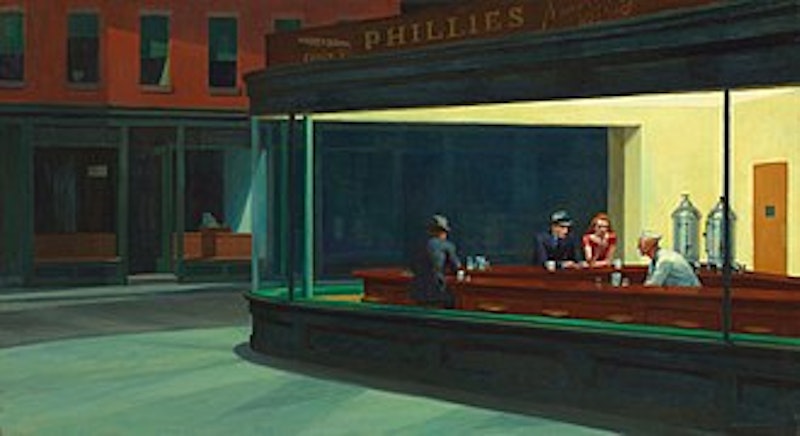

As World War II raged on during the early 1940s, in New York City widespread commercial fluorescent lighting just came into use. The setting is an all-night coffee shop, reminiscent of the historic triangular Flatiron Building with its large glass window. Four solitary patrons are framed in garish light. A brooding femme fatale dressed in red and mysterious men sit quietly. Outside in the darkness captures the tranquility of solitude, the wartime blacked-out metropolitan rooftop silence is broken by the constant frightening wail of air raid sirens.

There’s dispute over the diner’s original location. Some reports indicate the former home of Cafe de Bruxelles S-shaped bar, while others swear it was located around Mulry Square on 10th St. and Greenwich Ave. Speculation judging from Hopper’s preliminary pencil sketches, Nighthawks may be a composite image.

Hopper completed the final oil painting on January 21st, 1942. The priceless masterpiece sold quickly for $3000 then and now resides in The Art Institute of Chicago. Upon death, Hopper bequeathed nearly 3000 artistic materials to the Whitney’s permanent collection. For further discussions about Hopper’s work, Gail Levin offers her expertise in the biography Edward Hopper: An Intimate Portrait.

Back to our busy, no-nonsense diner with a “Sit anywhere you want.” waitress. She blissfully scurried back and forth across a blue linoleum floor. Two tattered counter stools stood alone; the third invisible stool was missing. Lined up hanging behind the counter, dull yellow menu signage listed specials. The diner clock ticks. This weatherworn ambience stands as a symbol of the past. Socking away our now forgotten pennies, the rules of destiny apply. Under a constant threat of closure, this place too will eventually succumb to the wrecking ball, be demolished and vanish into the unforeseeable future; washed away by the tides of progress. I stopped visiting for a while, but not because of a lack of affection for a greasy spoon. One day, I paid a higher price for a meal with an afternoon of digestive distress. Inexpensive restaurants are rare today, nobody bats an eye over a $20 breakfast special.

Stirring a coffee refill marked The Golden Girls arrival. Seated across at a Formica tabletop, a trio of anxious female tourists ready for a day of shopping or a possible Broadway matinee. Finishing my sandwich, I looked up for a moment. Running through my mind, a life insurance commercial that targets old folks airing every night during the six p.m. news; Jonathan Lawson’s overplayed Colonial Penn Life ad where the actresses talk endlessly about still using mom’s old coffee pot.

Nighthawks’ moments are often brief. My visit also served as a reminder of a Sunday afternoon a few years ago with the late Peter Koper and friends: an Edward Hopper studio tour. Hopper and his wife Josephine, lived frugally and worked at 3 Washington Square North from 1913-1967. The studio’s located on the eastern end of a row of Greek Revival townhouses in Greenwich Village. Here’s where the couple maintained a tumultuous 43-years-long relationship.

The building owned by NYU, saw Hopper fight eviction at one point saying, “The University is supposed to be an educational institution, in sympathy with the arts. Is this the way to show it?” Cementing his efforts to stay, Hopper won an appeal in 1946. This is where Hopper effortlessly dipped his brushes with deft gestures and created Nighthawks. Characterized by melancholic realism, charged in an atmosphere of loneliness, the painting stands as cherished hallmark of American culture.

With window views overlooking Washington Square Park, the humble fourth-floor space is preserved in pristine shape, keeping its cultural integrity. Ceiling skylights (which Hopper didn’t black-out during the War) brighten the time capsule. Filling the room, his easel and an etching press. No original paintings are kept here. Imagine, over six-foot tall, sullen Hopper carrying buckets of coal to his stove, up four flights of stairs until his very end in 1967. As an acknowledgment, NYU placed a commemorative plaque in front of the building.

How would Hopper feel about Nighthawks undergoing a present-day A.I. makeover? Look no further than “Visual Poems: Edward Hopper Nighthawks: The Silent Conspiracy at 2 AM.” The video tribute gives the painting a compelling modern-day context. The complex nature of human solitude falls between dream and reality. Algorithms analyzed imagery credited to Hopper and birthed a hybrid reality. It’s impossible to unsee the newborn offspring.

The negative aspects of today’s A.I. models come as no surprise to anyone who’s been paying attention. Bearing in mind, humans have a unique ability to apply artistic processes to convey truth, even when portraying falsehoods. Looking back, it’s challenging imagining Hopper’s thinking. If nothing else from what I’ve read, he could be brutal at times, possibly, somewhere along these lines:

“Lights going out and a kick in the balls.”