The amateur creators of ”Dial H For Hero" represented a fascinating cross section of early-1980s fandom: diehard collectors, elementary school kids, outsider artists, famous sci-fi writer Harlan Ellison, and a handful of soon-to-be pro-level creators, including Queens, NY’s Stephen DeStefano. Impressed by the “Dial H” contributions he made to Adventure Comics 483, a few years later DC began running the artist’s “Nick O. Tyme” one-pagers in New Talent Showcase (an interesting title made up entirely of debut stories from artists and writers who were just turning pro). Shortly after that, the company picked up DeStefano’s series ‘Mazing Man, one of the few mainstream 1980s titles to match the innovation of “Dial H” in its nuanced portrayal of comic book culture. Steve Mattsson was another aspiring pro whose career got a boost thanks to his “Dial H”work.

Writer Marv Wolfman and DC’s editorial staff decided early on that—unless there was an overwhelmingly positive fan reaction to one character or another—there’d be no repeat appearance for any of the reader-generated superheroes and villains. “Dial H For Hero” was an instant hit that inspired a tsunami of mail from fans and potential contributors. As a result, many times the letters pages of Adventure and Superboy included reminders of the no-repeat policy. With all involved aware of their character's temporal nature, the amateurs were inspired to push their imaginations. If their transient super entities were going to make an impact they’d have to be a thousand times weirder and more ridiculous than any of the established creations who benefitted from serialized appearances.

There’s no quick summary for this grand mass of inventive splendor. Each one of these characters reflected different kinds of morality, social circumstances, fantasy, and heroism. Here are the most memorable and outlandish moments of “Dial H For Hero”:

Adventure Comics 483 & 484: After five issues that only hinted at the feature’s wildest possibilities, these two kick open the floodgates with ideas blazing. Vicky and Chris transform into a bevy of wacked out heroes including Zeep The Living Sponge, a lovable orange, nose-less humanoid whose powers mainly consist of bouncing frantically; he’s got big red monochrome eyes and facial features like a trippy alien bumper sticker. Zeep was a DeStefano character and the artist’s first professionally published work. Other notables include symbiotic-energy blasting egalitarians Black & White (created by 13-year-old Wayne Hastings of Cantoment, Florida), and the Greco-Roman hero The Gladiator (created by a committee of kids from Farmingham Hills, Michigan: Jeff Zonder, age 11, Erica Zonder, age 10, Josh Gubkin, age 10, and Jenny Gubkin, age 7).

The super villains in these issues are just as special. Wildebeest (created by 15-year-old John Herbert from Wynantskill, NY) is an unscrupulous big game poacher whose tricky arsenal rivals that of any Batman villain; there’s no doubt environmentalist concerns gave birth to this globetrotting techno-thug. The Pupil (co-created by Bruce Smith, age 19, Monmouth, Or. and Steve Mattsson, age 17, Portland, OR.) is a floating robotic eyeball wearing a graduation cap; its technical construction resembles that of the helmet worn by 1960s fanzine hero The Eye. Finally, there’s Mr. Negative (created by Rudolph Minger of Hollywood, CA), a bitter, grizzled, homeless super villain who stomps around in a filthy trench coat hypnotizing people with his telepathic bad attitude thus injecting suicidal thoughts into the mass consciousness of Fairfax’s predominantly well adjusted population.

With the visceral art of Carmine Infantino, Marv Wolfman’s distinct sense of emotional complexity shines in a sympathetic story arc involving bully character Brad Mann (he is to Chris King what Flash Thompson was to Spider Man alter ego Peter Parker). Exploring the pathos at the root of all bullying, Adventure 484 finds Mann running away from home to escape domestic drama that arises from his parents’ divorce. Things gets crazier when he becomes homeless and seeks refuge with surly teen-street gang The Vipers.

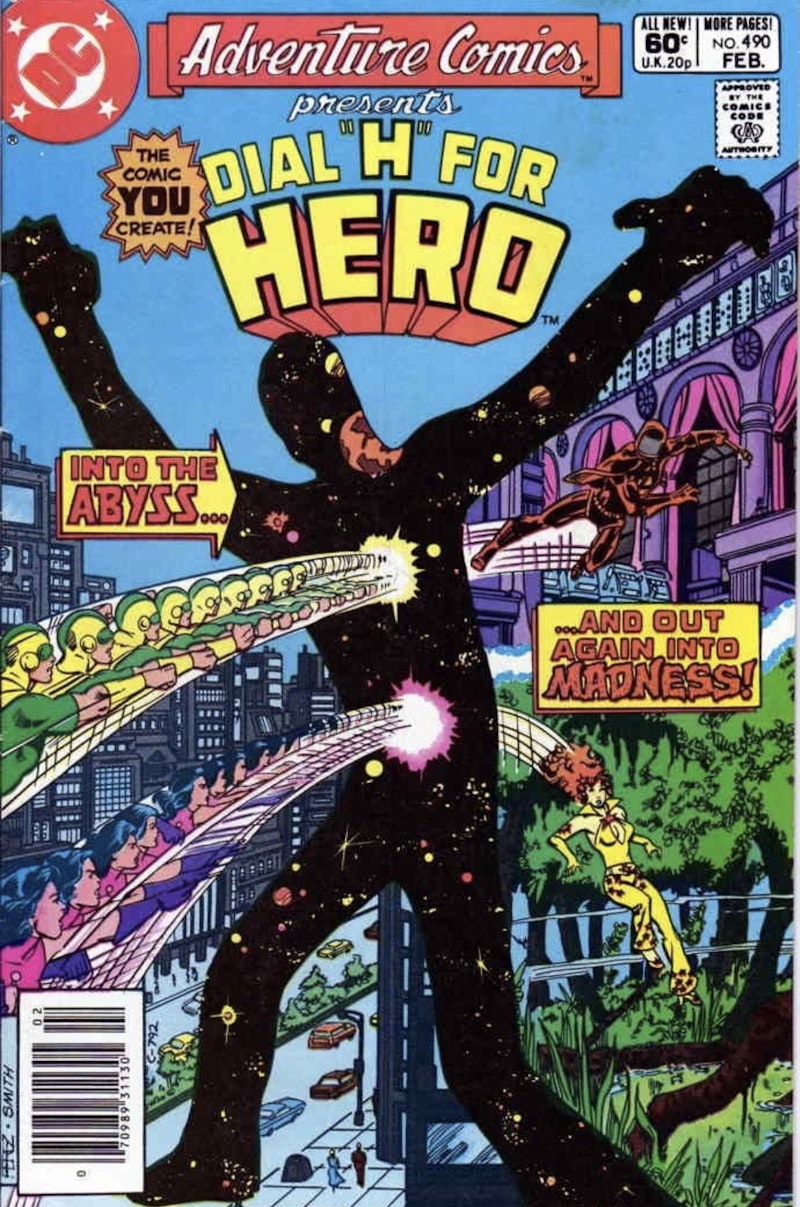

Adventure Comics 490: The three-part “Into The Abyss” saga ran in this issue. It was the final “Dial H” tale to appear in Adventure and the first written by the pro-creative team that featured scripter Bob Rozakis and plotter E. Nelson Bridwell. It’s the quintessential “Dial H” epic, a chaotic convergence entering around the rapid fire appropriation of 20 different fan-generated superheroes and villains making this into one of the most dizzying, dynamic, and surprisingly non-violent spectacles ever jammed into a single comic book. Mind-blowing efforts from two different art teams (Infantino & Legion Of Super Heroes’ Larry Mahlstedt in parts 1 & 3; Howard Bender & obscure fantasy art master Rodin Rodriguez in part 2) push the energy of this mini-epic into the stratosphere.

The New Adventures Of Superboy 37: It was weird to find a character created by a committee of little kids, but that was nothing compared to the aggregate who came up with Jimmy Gymnastic. Miss Niefield’s fourth grade class from Garden City, NY collectively invented this high-flying acrobatic jock hero (Chris King’s alter ego for most of this installment). Jimmy’s weapon of choice was a pole-vaulting pole, he zoomed around on roller skates, wore a bike helmet, dark-tinted ski goggles, knee pads, and his chest was emblazoned with a big “JG” in team letters printed on a bright orange/powder blue unitard. It looks like this guy crashed into the budget bin at a sporting goods store then stumbled out wearing whatever was left stuck to him.

The villain in this story—The Firecracker, created Larry King of Morrisville, Vermont—is a greedy demolitions expert who blows a hole into a Fairfax comic bookstore to steal rare back issues. Here’s a scheme that could only come at the birth of mainstream fandom, a time when early copies of Amazing Spider Man, Batman, and Superman were making headlines as they began to command four- and five-figure prices.

This was the first significant short form “Dial H” story. Art was handled by veteran inker Joe Giella and Howard Bender, a penciller whose iconic style was a powerful element of DC’s 80’s horror and sci-fi titles. Bender would remain the primary“Dial H” artist until the series concluded in Superboy 49.

The New Adventures Of Superboy 42-49: The 1980s “Dial H For Hero” finished with its most unconventional story arc. This included a sorcerous climax and two of its strangest characters:Chris King dials up a mute, non-human Q-Bert homage called Fuzz-Ball (created by Bob Mercer of St. Josephsburg, Newfoundland, Canada) while Vicky King becomes Raggedy Doll, a telepathic toy clad in French braids, a yellow/green mini-skirt, go-go boots, and fishnet stockings (created by Steven E. Talbert of Ohio’s Wright-Patterson Air Force Base).

The New Adventures Of Superboy 53: Fan letters for “Dial H” poured in for months after Superboy 49. Most contained predictable expressions of disappointment regarding the cancellation, but a letter from amateur creator Steve Mattsson published in Superboy 53 was more than a eulogy. Before gaining fame as a writer and colorist at Marvel and DC, and as a member of Dark Horse Comics’ early talent pool, Mattsson conducted a series of independent Dial H For Hero workshop events at the House Of Fantasy comic shop in the Portland suburb Gresham, Oregon. His efforts got special attention from DC’s editorial staff, including Len Wein (creator of Swamp Thing), Mike Barr (Batman and The Outsiders, Detective Comics), and “Dial H” writer/DC managing editor Bob Rozakis. These influential pros would help Mattsson make the move from enthusiastic fan to fulltime freelancer.

Corralling some of comicdom’s most original and eccentric amateur talents, Mattsson guided his crew of young hopefuls onto create 13 “Dial H” character submissions, all of which made it into print throughout the early-80s. He frequently eschewed formal co-creator credit and gave the spotlight to the workshops’ less experienced participants. He’d written to DC as a way to highlight his involvement and the significant impact that the workshops had on the feature’s ever-expanding hero roster. Mattson and his workshops proved that “Dial H For Hero” was a watershed moment marking fandom’s transformation from a disposable fad into a passionate communal outburst of imagination.