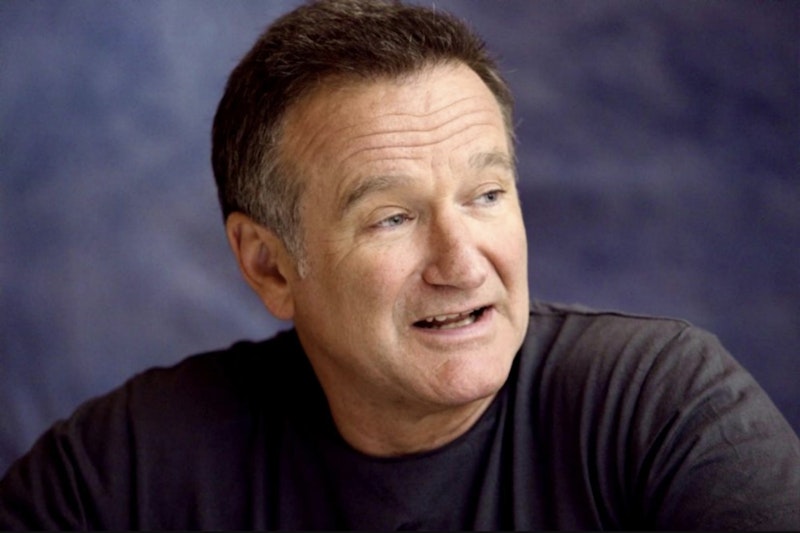

Nine years ago, we watched Robin Williams laugh himself to death. Or at least we watched as he laughed about the demons that tormented him during his life. He could giggle and gibe about being an alcoholic and a drug addict, as he did to middling effect in his 2010 comedy special Weapons of Self Destruction, while nevertheless continuing to struggle with alcoholism and drug addiction.

After Williams took his life and the requisite outpouring of grief had swept social media, a handful of acquaintances chided their followers for concerning themselves with the plight of a rich white man. In 2014, this was akin to being a little bit of a contrarian; today it’s fairly de rigueur, a sharing of shibboleths one guesses that others guess they want to hear. At the time—and now—my thoughts about Williams’ passing had nothing to do with his race or socioeconomic status. I was concerned with something else entirely: here was yet another person, benumbed by years of self-deprecating laughter, who’d shuffled off this mortal coil.

When I realized this, it almost broke my heart. Almost. “Buried another one,” my 75-year-old father—who died a few months later—joked during a phone conversation that took place shortly after Williams’ passing in early-August. I recall laughing weakly when he said this, because that was the only bond the two of us had left: morbid chuckles at some other unfortunate soul’s expense.

Biting absurdist comedy has always resonated with me. I cut my teeth on The Kids in the Hall, came of age with Mr. Show, and in the early-2010s sampled the various imitators following in the wake of these troupes (Tim & Eric, the now suicide-depleted The Whitest Kids U Know, et al.). For this refined sensibility I can thank my father, since he’d spent much of my youth stripping me bare, removing whatever traces of innocence or naivete he found. Once that ordeal had concluded, I could look back on it and laugh.

I laughed about it because I couldn’t do anything else. I couldn’t change it, I couldn’t redeem it, I couldn’t justify it. I could merely take solace in the fact that life was a joke. A somewhat funny joke, even if it was at my expense.

To be honest: I never thought that Williams was a great comedian. Passable, certainly, but his manic antics had a forced and somewhat artificial quality lacking in contemporaries—and fellow troubled souls—Andy Kaufman and Richard Pryor, who, while funnier than Williams, also weren’t as good as everyone now feels obliged to say they are. However, Williams far surpassed them as an actor, most notably when he was given an open-ended role in which to lose himself, as was the case in The Fisher King and The World According to Garp.

In blockbuster comedies, Williams’ jackhammer-subtle humor proved an impediment, a barrier between him and the audience that disappeared when he was allowed to discover himself underneath Popeye prosthetics or a world-weary therapist’s beard. The jokes in his comedy specials are delivered in a staccato manner that alienates even as it amuses, which is perhaps the point: he was hiding behind laughter because he had nowhere else to go.

I can’t speculate about why Williams was sad or why he felt impelled to be funny; that page-filling armchair psychoanalysis is best left to veteran feature writers hurrying to meet legacy-media word counts for their ever-scarcer print commissions. And Williams’ youth, at least in summary, sounds like a bed of roses compared to the lives of many others. But how can we measure pain, besides knowing it when we see it? When I caught glimpses of him in the years preceding his death, I saw a proud man who was gradually shriveling up and fading away. His physique, wrestler-solid in his prime, looked worn and small in a late-life appearance on the since-canceled FX sitcom Louie.

Spread across several decades, jokes-at-your-own-expense will exact a heavy toll. Part of my own maturation consisted of recognizing that not everything is a laughing matter; many aspects of life are sacred, or nearly so. As a parent, it’s easy to lapse into cheap Hallmark sentimentality, but bare existence, for all of its challenges and miseries, represents something greater than a series of “I’m eating from the dirty diaper again, boys” gags on shitposter @dril’s timeline.

In those moments when Williams was acting—the Juilliard prodigy in his element—he showed us a glimpse who he really was. The rest of the time, he kept us distracted, kept the fish-in-a-barrel guffaws rolling in like so many waves against the seashore. I know how easy and comforting that is: I did the same thing, albeit to far less acclaim, throughout most of my misspent, misremembered youth. If the people around me never discovered who I was, I thought, maybe I wouldn’t have to look too deeply at myself, either.

Robin Williams would’ve been better off as some sort of self-serious “method” thespian, a Daniel Day-Lewis or Joaquin Phoenix type willing to approach death in the service of his roles instead of choosing it in lieu of his actual life. When you see someone doing what they’re supposed to do, it’s splendid. But much of the time, we remain determined to hide from who we are, with lame humor serving as the perfect camouflage. Williams the reluctant comedian left this orb too soon—a cold, hard fact of life that’s anything but a laughing matter.