No one owes you anything for having a niche interest. The mainstream should make room for its subcultures: the outsiders, iconoclasts and geeks who exist on the margins. At the same time, those on the margins should recognize, relish and respect the place they occupy. Let the mainstream be the mainstream, and don’t spoil what makes your scene unique. As every aspiring fashion designer knows, once your product makes the leap from the boutique market to the big-box stores, it’s hard to maintain the same level of quality and specialization.

In our era of self-commodification and personal branding, every subculture has become subject to the logic of the influencer. No creative legacy or self-contained scene is too precious or sacred to leave alone, free from the strip-mining logic of “monetization.” Every work of art must “evolve” and refashioned into a “creative property,” superimposed onto the wider culture to become suffocating, inescapable and ubiquitous. Knowledge about this art has become yet another social tool you can leverage against others. It’s a superficial pose you can adopt and drop at your own convenience.

This explains why so many writers who focus on music, film or gaming have spent the last 10 years effortlessly cycling through various branded selves: the disagreeable know-it-all, the irony-poisoned shitposter, and the rose-emoji-clad extremist. The personal brands change, but they all insist on wearing your favorite music style, film series or novel as a mask. And so long as these cultural cenobites have the guts of your passion smeared all over their bodies, they’ll tell you the right and wrong ways to enjoy yourself.

Beyond the cynical logic of value extraction, I don’t get why people do this. All I’ve ever wanted was to carve out my own space and operate freely without trying to bother or change anyone else. I learned from unhappy years in middle school how much I hated the fake, gossip-ridden hell of group conformity and blind loyalty to cliques. From high school onward I took my friends à la carte—my birthday parties may as well have been a UN summit of social groups. I felt comfortable sitting at almost any lunch table, feeling I had at least a couple things in common with each type of person, while chilling out on the stuff that may have divided us.

I pursued what I genuinely enjoyed and became invested in them: history, a few gaming series, literature, and above all, music. And by music, I mean metal, grunge, punk, and hardcore. If you shared these interests with me, I’d probably annoy you into being my friend. If not, that was cool, I left you alone. Hell, even my athletic interests—skiing and martial arts—guaranteed that I didn’t need to bother anyone. I never saw the point of inflicting my passions on people. Why go through the trouble of alienating people? Why make the effort to become “that guy?”

The few times I was “that guy” felt awful. For the first few years I went to concerts, I stuck mostly to punk and hardcore shows in my state, and then worked with some friends in my hometown to build our own scene from scratch. Participating in an underground scene can give you a sense of commitment and loyalty to certain ethics and standards.

One day, I was hanging out in the center of town and saw an unsuspecting kid outside the movie theater wearing a New Found Glory shirt. I lectured him about how pop-punk was for posers who should get it together and listen to some “real punk” instead. But instead of returning my hostility, he was taken aback. The dude swore that he liked all the “true” stuff too.

I’d successfully intimidated a stranger about his taste in music. But I didn’t get any satisfaction out of this. All I felt was pity for him and shame for myself. Why couldn’t I just say, “Yo dude, that’s cool you’re into those guys, you ever check out The Descendants?” The joke was on me anyway. Even in the mid-2000s, the most basic online research would’ve shown that New Found Glory has roots in the hardcore scene, and their bassist was the singer on the first Shai Hulud album. And while Jordan’s vocals still aren’t my thing, I’ll crank “My Friend’s Over You” like every other nostalgic Millennial.

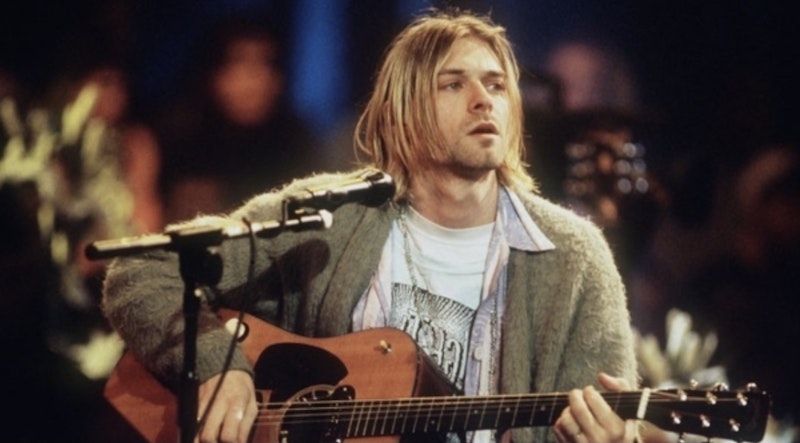

I knew what it was like on the receiving end of this attitude as well. I was cool with the jam band kids in my class, but one of them just wouldn’t shut up about how much he hated punk. He knew I was a huge Nirvana fan as well and loved to give me grief about that. “All they do is play power chords! That’s not real talent!” One time, we were at my neighbor’s house watching a video of Phish engaged in one of their endless, meandering jam sessions. “SEE! TREY has real talent, Kurt Cobain is NOT good at guitar!” That’s right, if you get some “real talent,” you can churn out an ersatz rehashing of the Grateful Dead night after miserable night. I remain unconvinced.

It’s always a mix of snobbery and ignorance. The hardcore guy I met who said that Nirvana’s acoustic stuff was when they turned into crap and that Nevermind was the last hard thing they ever did (I had to remind him that In Utero existed). The Gen-Xer who scorns any punk after the late-70s, but couldn’t name a ‘77 band other than the Sex Pistols. The metal frontman who gets on stage and insults the band who just played, “Enough of that hardcore bullshit!” even though the two scenes have been linked since the early-1980s.

After you file away the specific features, it all reduces to someone yelling at you: “I’m different and you need to recognize how that makes me special… and then you need to become more like me!” It’s the logic that went into the insane initiative in the UK several years back to add “goths” as a category protected by hate crime legislation. It’s the logic of someone who insists on being on the margins, but isn’t secure enough to be comfortable there.

Back in 2008, I was once talking to the cashiers at St. Mark’s Comics. That was my first mistake. My second was to bring up how excited I was about The Dark Knight. The response I got from one pudgy associate was “I don’t know much about it, but I know it’s going to suck.” His reasoning was Batman Begins’ apparent infidelity to the comics. I registered the only response I could think of: “But it’s a movie, you have to make it compelling for a moviegoing audience.” I then made the third mistake of talking about how much I loved the first two X-Men films, to which they scoffed: “Those are awful too, they’re basically just Wolverine movies.”

Guess what, genius? As the people at Red Letter Media have explained, stories that take place within a fantasy, superhero, or science-fiction setting often need a relatable character the audience can identify with. Wolverine is someone we can envision sitting next to us at the bar. He’s in on the joke with us, but still has claws and sick healing powers. Absent a character like this, the world built by the story can seem alienating or even laughable, as we’re less apt to feel invested in it and suspend our disbelief. Fealty to the comics might satisfy your sense of superiority over others, but it won’t always make for a good film.

You know what else is great about those early X-Men movies, along with Blade and the Sam Rami Spiderman movies (you know Marvel movies not in the MCU itself). Plotlines have consequences. Violence results in blood, pain and suffering. People die and don’t come back. These movies have problems, but you still get the feeling they exist as earnest creative efforts, rather than ballast to prop-up other CGI-soaked “tentpole properties.” They don’t just feature someone getting their stomach slashed with a knife and have zero blood to show for it (like in the new Black Widow film).

But great news, nerds, you won! We’re stuck in one giant locker with you, forever! You’ve remade the world of cinema in your image. Hardly anything is financially viable if it isn’t marketed to 10-year-old children (and 45-year-old children). Your precious world of fantasy and adventure has been fully integrated into trade shows, corporate sponsorships, geopolitics and even identity politics. You’re the mainstream now.

It’s cool when your little world gets its moment. But after some time, it’s good to settle into a steady rotation in the outer reaches of that solar system. Star Wars gave us three great blockbuster movies so many people loved (myself included), but then it went away and we could enjoy it for the place it occupied. And to get back to music, it’s cool that Metallica’s black album went diamond, or that death metal had its major label breakthrough moment in the early-90s. These moments of mainstream notoriety help feed niche and underground scenes with new blood and extend their lifespan to new generations.

However, we need to bring a sense of balance to subcultural production. To be a geek or nerd is to be interested in something to the point of encyclopedic knowledge and obsession. There’ssomething weird and odd about it, as it’s typically not something tied to basic survival or financial stability. This is why it’s easy to make fun of, because it’s a little absurd. It recalls Oscar Wilde’s formulation about art as being “quite useless.” But this is also what makes it special.

There’s a genuine thrill in being among your fellow obsessives. In those settings, I can go on all day about the platonic ideal of black metal. Or how the use of noise-gating and compression ruined most metalcore after 2008. I’ll tell you how I despise jam bands, ska and folk punk, or how 90 percent of post-grunge is featureless, derivative garbage. But outside of those settings, if you like that stuff that’s cool. We can talk about the weather, food, pets, home improvement, or whatever you want. Suit yourself, I’m easy.

George Orwell’s 1984 is a nightmare vision of his own political ideas rendered as a totalitarian dictatorship. I wouldn’t want my taste in art and music to become the mainstream consensus. Having a niche interest doesn’t give you special purchase on respect and authority, aside from the purchases you make as a consumer. Victory in that case becomes its own defeat.