Comics weren’t a huge part of my childhood. Newspapers were outdated by the mid-2000s, and most of my entertainment came in other forms than the “funnies” section. But when I was given a Calvin and Hobbes collection, I couldn’t get enough of it. The strip was already long retired, but it never felt dated. I read every book, loved every character, and they stuck with me even after I moved on to reading novels.

2020 marks a double anniversary for the series: the 35th anniversary of its beginning, and the 25th anniversary of its end. I recently reread Calvin and Hobbes in its entirety, to see how I felt about it as an adult. I loved it even more.

The depth of storytelling and variety of ideas is amazing. Bill Watterson conveys so much without words. In many panels, the characters’ expressions show the story. Watterson often plays with time jumps: he displays just enough to understand events and characters’ reactions while leaving out just enough for us to wonder what happened between the gaps. We share Calvin’s perceptions and emotions while seeing the world through the lens of his imagination.

Calvin should be insufferable to readers with his immature antics. He’s constantly pestering Susie, making Ms. Wormwood’s job difficult, and distressing his parents’ lives by destroying furniture, sculpting deranged and twisted snow creations, flooding bathrooms, and flunking his classes. But because of this mischievousness, we love him more. His vocabulary is impressively, impossibly large, and the philosophical moments are also memorable. Calvin ponders life, love, war, God, Santa Claus, morality, the universe, cookies and tigers. Hobbes sarcastically grounds his thoughts back to earth:

The range of his contradictory thoughts and behaviors make Calvin feel real like a real kid, not a caricature. He struggles with many of the same things we all do: the pull between wanting personal freedoms and control over his life, while also absolving himself of responsibility when things go awry:

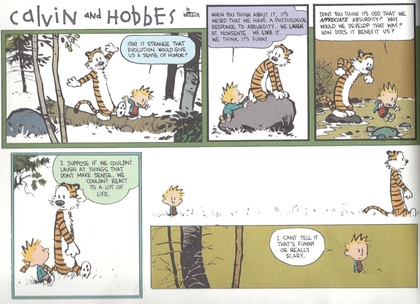

He’s sometimes frozen by cynicism and existentialism, wondering why we go to all the troubles we do when things fall apart in the end anyway:

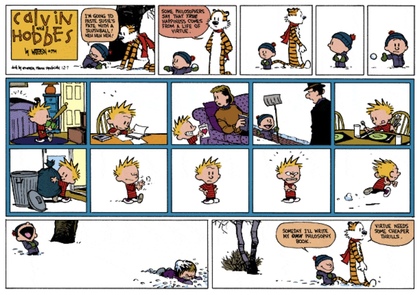

He hates school for its one-size-fits-all, sit-down-and-shut-up dogma. He struggles with his place in life, wanting to both jump ahead to the future and live blissfully in the present. He teases his parents for their adult responsibilities while desperately clinging onto his own youth. He can’t figure out if he wants to be good (especially when Santa’s presents are on the line) or give into his mischievous temptations:

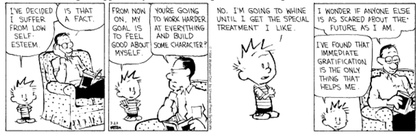

He longs to be famous and successful for his great works and accomplishments, yet is content to sit around waiting for opportunity to find him in glorious, instant gratification:

Calvin also has that talent many kids seem to share: a blunt way of describing things the way they appear to him, free of the constructs we adults impose and the things we take for granted without hardly a thought as to why:

Calvin feels like so much more than just a two-dimensional drawing. The supporting cast is excellent, especially when they make fun of Calvin. I used to roll my eyes at Calvin’s dad for his monologues and adages about building character, but now I notice he has some of the more prescient lines in the series:

As Watterson earned creative freedom, the strips got better through the years—more elaborate storylines, varied pranks, diverse scenes and locations, and a wider glimpse into Calvin’s imagination. This is reflected in Watterson breaking the mold of the traditional comic strip format. The dailies became more than just four panels, but often one, two, three, or more. Sunday strips especially became dynamic and memorably unique, intensely detailed scenes with more vibrant colors and different panel arrangements.

The series never sold out. Watterson fought against numerous merchandizing, television, and movie deals. In denying any adaptations, Watterson granted readers the freedom to imagine our own voices for all of the characters. Calvin and Hobbes successfully fended off the commercialization it so expertly critiques—it lives on because of its own merit, not because we’re constantly reminded of its existence through t-shirts, annual holiday specials, and the back covers of cereal boxes.

Nostalgia is a powerful, and I worried that I wouldn’t enjoy the series as much as an adult. But rereading it taught me more lessons in humor and philosophy and revealed a greater depth to the strip. Somehow, Watterson was able to enthrall millions of fans while stretching the boundaries of the comic strip as a medium. Reflecting on it, he said, “Punchlines come and go, but something in the friendship between Calvin and Hobbes seems to hold a small piece of truth. Expressing something real and honest is, for me, the joy and the importance of cartooning.”

The joy of Calvin and Hobbes springs from how real the characters feel. We see ourselves in them, both as children in the past and adults today. I like to think the characters Watterson drew into life are still out there somewhere, going for wagon rides and daydreaming in math class and pelting each other with snowballs.