Often seen as inaugurating television’s second golden age, David Chase’s The Sopranos was less the promise than the fulfillment of that brief moment when television seemed capable of delivering on the level of film. The Sopranos isn’t a show so much as one long, great American movie. And it’s our story in a way The Godfather isn’t.

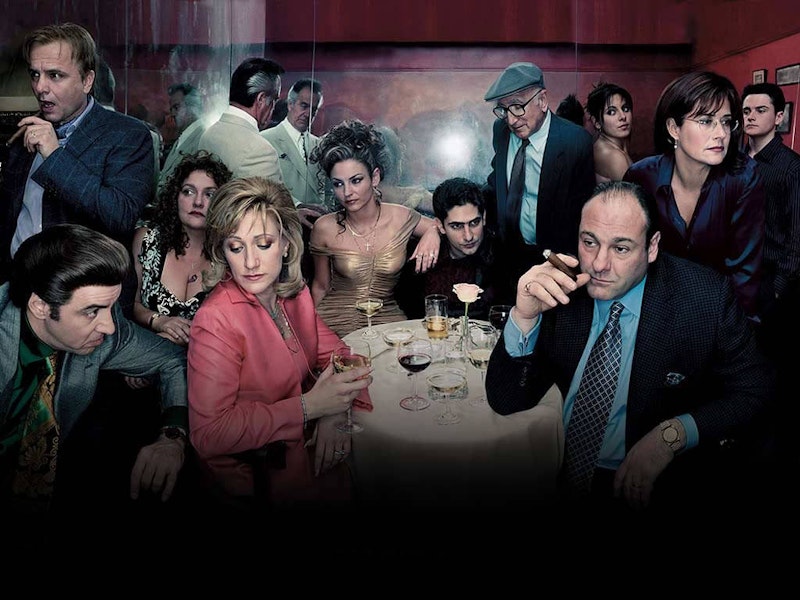

The tragicomic story of a New Jersey mob family headed by Anthony Soprano (James Gandolfini), The Sopranos is also a sophisticated moral tale. This explains the oft-noted similarity to Scorsese’s oeuvre, but The Sopranos has more black comedy and far less Christian guilt than any of Scorsese’s movies (in the structure of the story, that is—within the story there is plenty, beginning most obviously with wife Carmela). In Goodfellas, for instance, or The Wolf of Wall Street, Scorsese only allows himself to dive into exuberant amoral humor because he knows that a moral ending will follow. Henry Hill in Goodfellas faces the consequence he most fears: he becomes nobody. And similarly, in Wolf, the main characters get what they deserve.

In Scorsese’s movies, we’re presented with a thoroughly moral universe in which sins are punished—or should be. But the world of The Sopranos has little of this. While plenty of characters die, their deaths are rarely understood as moral recompense for their actions. They die because of the high probability of death in their business, because they miscalculated at a crucial time, because they angered a higher-up in the paramilitary structure of their organization, or because they betrayed that organization. Those who prosper do so largely because they make better decisions than those who fail. The set of virtues is decidedly pre-Christian.

The purpose of the show isn’t to present and condemn sinners or “sociopaths,” but rather to present an alternate morality—one in many ways taken over from what remained of ancient Rome in the 19th century and still essentially pre-modern Italy. There’s a joke that appears several times throughout the series. Tony’s daughter Meadow is trying to intellectualize the mafia as coming from “the poverty of the Mezzogiorno,” where alternate methods of law and problem-solving prevailed. There’s something funny about the pompous way she presents her theory, and it plays well for laughs. But she’s also hit on something not altogether false. Regardless of protestations of Catholicism, the mafia’s structured around an essentially Roman concept of virtue: courage, manliness, discipline. There’s little room for the Christian virtues of humility and temperance. Some of the rewarding tension in the show comes from the fact Carmella (Edie Falco) tries desperately to have it both ways: she wants to be a good Catholic, but she needs to be a good mafia wife. It’s only in later seasons that she becomes painfully aware of the impossibility of being both.

Consider here the death of Christopher Moltisanti, Tony Soprano’s nephew and heir apparent. After repeatedly relapsing into heroin addiction and lying to his uncle about it, Christopher crashes a car with Tony (and an empty baby seat) in it. Tony, exasperated by the junkie that his beloved nephew has become, refuses to help him out of the car, and instead plugs up his nose so that he suffocates on his own blood. And yet, the audience can’t feel entirely alienated from Tony even here. We’ve followed the same saga of Moltisanti’s drug addiction—as well as his laziness and ineffectualness. Can we blame Tony for what he does? He’s dead weight, a failure, and a disgrace—and a danger to his family.

A similarly surprising assessment comes with The Wolf of Wall Street. We’re forced to conclude that even if the drug-addled, party animal stockbroker is not the highest human type, he’s nonetheless better than most of the options in society. Would we rather spend a week at Stratton Oakmont, snorting blow and tossing midgets in reckless abandon, or in some woke classroom, preening ourselves on our moral virtue and soberly discussing new gender forms and white privilege?

Likewise, in The Sopranos: isn’t it better to take than to buy into the dull farce of the American dream? The question remains: a free man, in the ancient world, was one who controlled his own time. Better to be free and in jeopardy than to be a work-worn Prufrock. Here the self-understanding of the mafia in The Godfather and The Sopranos is one: we refuse to work for crumbs, to be the imported laboring class of this county; we’re going to take what we want.

The Sopranos is also worth watching because it’s funny. The very idea of a mafia don going to a psychiatrist is hilarious. Some of the best scenes are those built around the quiet unfolding discussions between Tony and Doctor Jennifer Melfi (Lorraine Bracco). The intimacy that develops in her office is hinted to be in many ways deeper than what Tony shares with anyone else in his life. Their conversations risk all because they present true motivations and desires, and it’s only because of this risk—which sometimes goes horribly wrong—that both doctor and patient approach the truth about themselves and their lives.

Another thing the show does so well is to present the audience with a comparison for every claim it makes implicitly. We see Tony’s crew busting out a store to collect a debt. This seems cruel, but then we see what led the owner to such a pass. And in many ways we’re more revolted by him than by the men who pick apart the carrion of his life. Chase and his collaborators force us to ask an important question here: can we even conceive of a world without organized crime? After all, if there will always be “degenerate gamblers” and drug addicts, won’t there also always be someone to profit off them by providing what they crave?

Another example: throughout the series we see Tony and Carmella struggling for self-understanding. At times it’s painful, and often very funny. We laugh at them. But if this were the whole point, we’d see, for comparison, a class of psychologists who have a deeper self-awareness and better lives. But is this what we see? Instead, we’re presented with Tony’s own analyst who steps in and out of a marriage, and ultimately abandons her patient when he needs her most and after assurances that this is something she’d never do. And why does she do it? Essentially because she can’t stand being mocked by her fellow analysts—a company of self-satisfied yuppies with sticks up their asses.

Crucially, when Melfi decides to “terminate the treatment” she uses a study as the excuse—but a careful viewer will remember that she acknowledged and dismissed the claims of that, or a similar, study early on in the series. She’s therefore self-deceived in order to justify her desertion of Tony Soprano. (Consider also the laughable caricature of a self-important therapist played perfectly by Peter Bogdanovich).

The gangsters don't seem so bad! Some are stupid, most are uneducated (Hesh an exception), but no more so than Americans in general. What Chase satirizes in the show is frequently modern America itself, not the mob specifically. The virtues they live by are preferable to late-20th/early-21st century America. They take genuine joy in life, in their own strength. They’re not whittled down by moralistic blather. Like the brokers in Wolf, they’re a breath of fresh air by comparison.

The foolish, weak, and pretentious ex-husband of Dr. Melfi might be the best example of this kind of comparatively base, hypocritical and unlikeable alternative to the Soprano crew. In an early episode he lectures her: “Call him a patient? The man’s a criminal, Jennifer. And after a while, you’re going to get beyond psychotherapy with its cheesy moral relativism—finally you’re going to get to good and evil, and he's evil.” With this speech, Chase sets up the way his show will be read by many critics and viewers; but it’s clear in context that we’re supposed to be at a minimum very skeptical of the claim contained in it.

The Sopranos also bears repeated viewings because it’s a show about America’s decline. It’s captivating because it’s straightforward about the all-important realization that our best days are behind us. Tony says exactly these words in the pilot episode of the series. And while he means this about the mob, Dr. Melfi immediately adds “a lot of people feel that way”—i.e., about America.

But the show doesn’t browbeat its audience with any of these issues—like the lesser The Wire or even Breaking Bad. It plays with them. We accept the fact of American decline and yet enjoy the jokes. We’re also fascinated by the way the characters play their hands. Tony, for instance, repeats this awareness of what his own time lacks throughout the show, yet he also delights, even revels in the life he has chosen. One of the best scenes in the series takes place before Christopher’s death, when the two of them stumble upon a crew of lesser criminals ripping off wine from a restaurant. Drunkenly, exuberantly mocking them, the Sopranos rob the robbers, and then get drunk on their wine. It’s as good as a scene out of Petronius or Rabelais.