Percy Shelley’s line that poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world is usually taken to mean that poets introduce and articulate ideas which go on to shape the world as a whole. And by that standard you wonder if you can call Dennis Joseph O’Neil a poet. O’Neil was a super-hero comic book writer who died in early June, and to look at his career is to see work that’s had a major cultural impact.

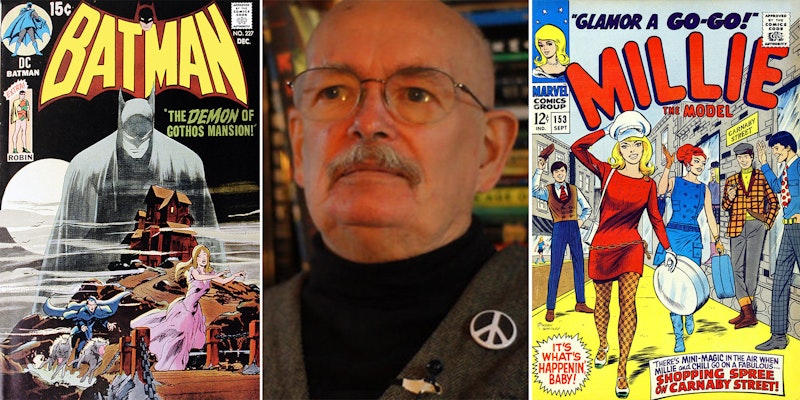

O’Neil was for a long time best known for the Green Lantern/Green Arrow series in the early-1970s, which covered social and political issues with a frankness then new in mainstream super-hero comics. He was also known for reshaping the character of Batman, notably creating (with artist Neal Adams) master villain Ra’s al Ghul, later a major character in Christopher Nolan’s Batman Begins.

At Marvel, a multi-year run on Iron Man saw the creation (with artist Luke McDonnell) of industrialist Obadiah Stane, AKA the Iron Monger, who a couple of decades later would be the main villain of the first Iron Man movie and key to the entire Marvel Cinematic Universe. O’Neil also briefly worked on the development of a comic based on a line of shape-changing toy robots, for which he created the name Optimus Prime. And, as an editor on Daredevil, he gave young artist Frank Miller the chance to write the book.

Born in 1939, O’Neil turned to comics after serving in the Navy and then working as a teacher and journalist. An article about comics led to a brief stint at Marvel, after which he moved on to Charlton Comics and then DC, where he wrote Wonder Woman and Justice League before taking over the poor-selling Green Lantern title with artist Neal Adams.

He added the low-powered Green Arrow to the book as a left-wing foil and conscience to the more conservative Lantern, and the two hard-travelling heroes went on a road trip across America. They stumbled into adventures that involved themes ripped from the headlines: overpopulation, drug abuse, environmental degradation, and the corruption of big business. The book helped show a new generation of writers entering the field how much was possible.

O’Neil was also writing Batman and Detective Comics at about the same time, frequently with art by Adams. He consciously tried to steer the tone of the books away from the recent popular TV show, and toward what he viewed as the darker, pulpier roots of the character. In so doing, he set the tone for how Batman would be seen for decades. Runs by Steve Englehart and Marshall Rogers later in the 1970s and by Frank Miller in the 80s would expand on O’Neil’s approach to the character—as would Tim Burton’s two Batman movies, the Paul Dini/Bruce Timm animated TV show, and the Christopher Nolan films.

In 1980, O’Neil was hired back at Marvel as an editor and writer. His most notable work was a long run on Iron Man (mostly drawn by Luke McDonnell) that expanded on a previous storyline in which Tony Stark battled alcohol addiction. O’Neil’s said he’d struggled with alcohol himself, and he drew from that experience to turn Stark’s alcoholism into a multi-year storyline that culminated in issue 200.

Returning to DC later in the 80s, he produced what’s arguably his strongest work as a writer, a three-year run on The Question with artist Denys Cowan. All O’Neil’s strengths came together in this book, using a pulp mystery-man to present philosophical and artistic themes, with ideas integrated into adventure-story plots.

O’Neil also returned to Batman, this time primarily as an editor. While he wrote a few stories—notably the first arc in the anthology series Legends of the Dark Knight—he mainly guided the other creators who shaped the character’s development from 1986 to 2000. He oversaw the death of one Robin and the introduction of another, as well as extended storylines in which Batman was crippled (Knightfall) and Gotham City was struck by an earthquake cutting it off from the outside world (No Man’s Land).

O’Neil described himself as a commercial writer, shunning anything that smacked of high art. He was a conscious and conscientious craftsman, and when you read his work you can see him refining his writing over the years: dialogue grows terser, plotting sharper. Yet he also had beliefs that guided him, a political worldview. In an interview in the late-70s he said, “It was part of my agreement with DC that I will not be asked to write a story glorifying war because I don’t believe that war is ever a good thing and I would not feel comfortable with a military hero.” As it happened, he’d go on to edit G.I. Joe for Marvel a few years later; but he insisted that the book didn’t glorify war.

O’Neil tended to break down the heroes he wrote about. In his early days at DC he de-powered Wonder Woman and Superman in his brief runs writing those characters. Under O’Neil Tony Stark lost his Iron Man armor. The first issue of The Question saw the hero beaten to the point of death, from which he returned as a very different character.

Most famously, O’Neil had Batman turn away from high-fantasy camp to brooding pulp thrills, and then in the 1990s as editor oversaw a storyline in which his back was broken. That was part of an extended arc designed to show who Batman was, and why Bruce Wayne in particular worked as Batman in a way other characters wouldn’t. Here as elsewhere, trials and tribulations define character. And, in the long run, O’Neil rebuilt his characters, stronger for their victories.

O’Neil was representative of a generation of comics creators, who imagined characters and stories that became essential to the mass media and the dream-life of millions. Too many of them remain less famous than their creations. Someone like Dennis O’Neil can’t be called a poet. But there was something of the unacknowledged legislator in him.