If all of us were to rediscover our old history notebooks, I’d venture that a fair portion of them would have margins filled with awkward sketches catalyzed by background, sanitized professorial droning of weaponry, death, and all of those other delightful things that come along with the theatrics of war. I’ve always been charmed by the pure weirdness and astuteness of juvenile creative expression, and the wisdom of the unconscious.

Is it just as charming when it comes from people who are well past their teenage years—or is it just bad art?

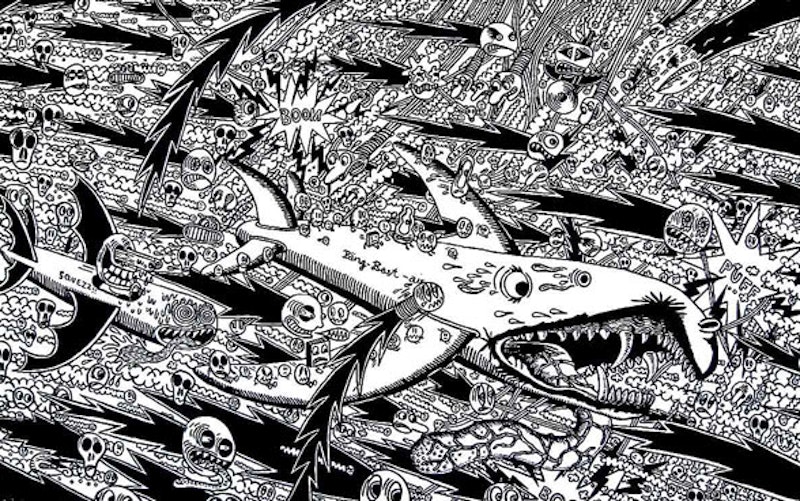

Bastokalypse, by M. S. Bastian and Isabelle L., is either an epic paean to the apocalypse, or a hugely self-indulgent mess. Uniquely presented as a continual scroll that measures 43 feet in length (and about one foot tall), Bastokalypse is described as a series of 32 wordless “graphic novels.” Each graphic novel is a black and white canvas that merges seamlessly into the next canvas—and every one of them visually describes some aspect of the end of the world. The concept itself is stunning, and the accordion-fold book itself is a smart and accurate presentation of something meant to operate continually, like many older Japanese narrative paintings. The original showing of these works in full size measured around 168 feet long, a presence which likely had more of a visceral impact.

Bastian operates under the art brut school of composition and aesthetics, frequently calling upon such horribly overused clichés as Mickey Mouse, Ronald McDonald and Gumby, as well as an unapologetic disregard for everything but gross over-complexity.

Bastokalypse itself is a sprawling, tangled series of drawings that look as if they were predominantly inspired by Rat Fink and The Nightmare Before Christmas. None of them actually express skilled draftsmanship, or beauty, or even a sense of ugliness. They just kind of are, all crammed into this expanse, but still battling for enough room to breathe. The impression of obsession and frenzy within the image seems forced, even if this work encompasses the efforts of a full decade.

As art observers, we have a contentious relationship with the “artistic scrawl,” and typically react with statements that discuss which of our pets or children could create comparable works. Many of us don’t really bother to explore the intent behind a work if it immediately strikes us as ugly, and that’s fine. It’s a line that the artist has to draw between creating for oneself or creating for an audience. If the artist chooses the latter, it’s necessary to build in a point of accessibility. It doesn’t have to be an obvious one, but without it, it’s like building a house without a door. Of course, excessive accessibility and an appeal to the lowest common denominator is just as cheap as including no access at all.

The back of the piece is a prolonged essay about apocalyptic imagery, accompanied by a number of visual references which Bastokalypse obviously borrows heavily from. The fact that an enormous scholarly essay exists to justify what’s happening on the face of the work makes the whole deal a little hard to swallow.

Bastian has said in multiple interviews that he is “confused” about life, and that his work is an attempt to understand life and himself. As a viewer, I’m not sure where we fit into his explorations, or who among us might have 63 feet of contiguous space to attempt to dive into it all as it’s meant to be explored. It’s a noble attempt at greatness, and it’s apparent that the artists have reached some kind of catharsis, but I’m left feeling detached from it all. I’m not one to flippantly dismiss 10 years of concentrated effort, but I’m not enough of an art snob to pretend that I really get it either. I keep on searching for one really good, really insightful drawing in this hellish Where’s Waldo, and I’m coming up empty-handed.