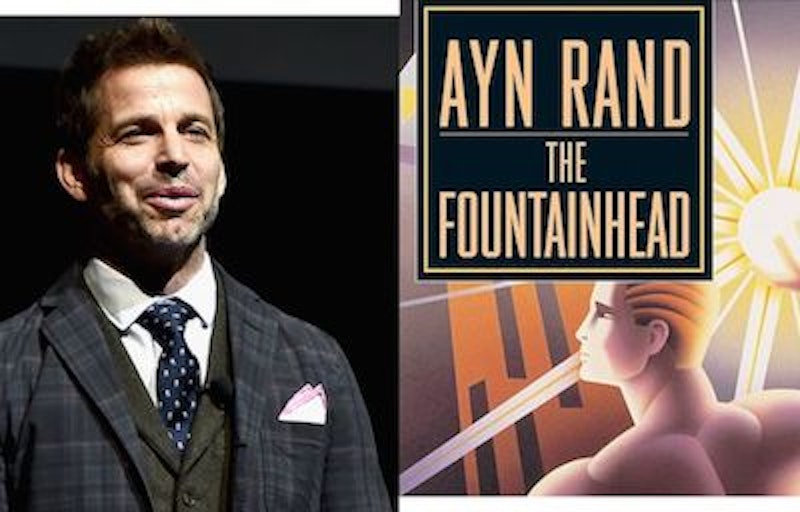

Director Zack Snyder says his next project is an adaptation of Ayn Rand’s novel The Fountainhead. That’s all he said, very briefly, on social media, so believe it when you see it. But consider the possibilities.

He may have gotten the current DC Comics film universe off to a shaky start, cranking out three of its five entries so far, but he’s basically competent and understands the current era’s push toward interconnected film universes. Why not have him launch a whole “Randverse” of big-budget Ayn adaptations stretching on for years?

He might not be well suited to subtlety—the DC Comics films have been called ponderous—but that could work well with Rand’s larger-than-life, operatic characters. When I saw Snyder’s visually bold adaptation of Frank Miller’s comic book 300 (about Greek vs. Persian warriors), one of my first thoughts was that he was the sort of person who should be adapting Rand, not the (well-meaning but doomed) people who were then planning an anemic, realistic, low-budget film trilogy based on Rand’s novel Atlas Shrugged. Rand jaws should be lantern-jaws, Rand speeches should be epic speeches, and Rand skyscrapers should be dizzying almost to the point of defying physics.

Fittingly, I saw the 300 movie with an expatriate Russian woman, who loved it. It was all the freedom-fighting she’d come to this country to embrace combined with the superhuman propaganda-poster aesthetic she’d been born into, which is roughly immigrant Rand’s own story.

The hypothetical cinematic Randverse needn’t literally involve works all set in the same fictional universe—Rand’s characters don’t recur from novel to novel—but the films could have recurring stylistic elements, occasional recurring actors, and obviously recurring political/philosophical themes, sort of like Stephen King or Tyler Perry adaptations.

I’m not promising I’d love these movies even if they're done well. Ayn Rand’s philosophy has two main components, egoism and strong property rights, and I agree only with the latter. Strong property rights keep government at bay, which is crucial to human flourishing, but egoism can sometimes just lead to all those stories about Rand fans being self-absorbed jerks.

The more devoted Rand fans would love to characterize any Rand-doubter such as me as an unprincipled hippie, but she’s the one who’s a no-good communist by my standards. Not only did she want a centralized government-run justice system (albeit a small, inexpensive one that does little beyond protect property rights), whereas I do not, she made the same mistake as nearly everyone across the political spectrum: thinking that altruism and pro-government sentiment are correlated.

Marxists are wrong to think it’s warm-hearted and self-sacrificing to want government to exist, wrong to think it’s callous to want laissez-faire capitalism. Ayn Rand is also wrong to think it’s gooey and self-sacrificing to want government to exist and flinty and self-centered to want it gone. Marx, Rand, and everyone in between—such as the so-called Bleeding Heart Libertarians—who encourage the ultimate lie that laissez-faire is cruel and government is compassion, are all in essence pushing for the same socialistic, Dickens-reading, humanity-disparaging model of the world, and I oppose it.

In short: Don’t be an egomaniac. Be kind. Get rid of all government.

The Fountainhead, unlike Atlas Shrugged, really can’t be counted on, by my standards, to get across a solid anti-government message. The Fountainhead is about an architect with so much artistic integrity that he doesn’t listen to haters (which is fine but a story any leftist artist could tell, really), whereas Atlas is actually about a big government regulating the economy to death. To a full-fledged Randian, it’s two aspects of the same fundamental story, but I’m not so sure.

I think you can absorb Fountainhead and merely learn to be pushy, not necessarily be drawn to any subtle policy debates—such as, say, whether the nationalist government of Italy should start producing its own currency or whether the UK government is wrong to put Tommy Robinson in jail for reporting on court proceedings related to Muslim rape gangs (or for that matter to forbid reporting on more elite, government-tied pedophile rings there, as they have).

Fountainhead, in other words, is about one percent policy and 99 percent attitude, a bit like Jordan Peterson or the fight-craving crowd of Millennial males I saw at a Chuck Palahniuk reading a decade and a half ago, who probably went on to become alt-right types a few years later. Fountainhead is not a work whose climactic courtroom scene necessarily leaves one craving, say, an independent judiciary.

I wouldn’t count on Snyder being nuanced enough to worry about non-“attitude” philosophical issues, either. We know him mainly from adapting the work of others, be it left-anarchist Alan Moore’s grim superheroes in Watchmen or the ancient warriors of somewhat Rand-admiring yet vaguely fascistic comics creator Frank Miller. The main thing we’ve probably learned from those adaptations is that neither Snyder nor Miller really understands the kind-hearted idealism of Superman, though they get the darker, more cynical appeal of Batman.

That may not bode well for depicting Rand characters as warm and human—but again, I’m not entirely convinced Rand’s characters deserve to be seen as warm and human, even though I’m rooting for them against the government.

Snyder’s most personal, most original film was not great, and strangely enough, it felt more cobbled-together and artificial than his adaptations: Sucker Punch, an iteration of the increasingly-popular (and creepy) Hollywood theme of teens tortured in mental-hospital-like facilities until their traumatized minds literally escape to alternate realities. Is Hollywood trying to tell us something about what goes on there? We’ve all heard the conspiracy theories by now, you know. Or perhaps this is just how self-hating Hollywood people see the real role of entertainment in a twisted, escapist society?

Whatever it is that makes that theme appeal to the makers of sci-fi, “young adult” fiction, and superhero films lately, by next summer, for example, it appears we’ll have seen five X-Men movies in a row that depict manipulative, occult, molester-like organizations kidnapping teens or young adults and toying with their minds (X-Men: Apocalypse, Logan, Deadpool 2, Dark Phoenix, and New Mutants). It wasn’t always this dark in the comics. Will it be this dark in Snyder’s hypothetical Randverse? That could get very Nietzschean and Germanic and scary.

Like 300 and Palahniuk’s Fight Club, it might at the same time end up being oddly gay, though, not that there’s anything wrong with that. When not doing films, Snyder has also directed rock videos for effete Islam convert Peter Murphy and effete Islam critic Morrissey.

But hey, no political or cultural faction should be expected to resolve every detailed policy issue right out of the gate. Equality and traditionalism, favorite impulses of the left and right, can certainly be vague attitudes as well. Maybe it’s all right for the libertarian impulse to take amorphous, expressive form sometimes instead of spelling out a detailed definition of “externality,” “contract,” or “estoppel.” I’m sure back when (egomaniac and non-libertarian) Angelina Jolie wanted to star in a production of Atlas Shrugged by (Ukrainian) Vadim Perelman, director of House of Sand and Fog, they weren’t motivated by a fascination with marginal tax rates.

I keep hoping all our culture’s strange twists and turns will lead back one of these days to a serious debate over how big the government should be, not endless debates over who’s a jerk.

—Todd Seavey is the author of Libertarianism for Beginners and is on Twitter at @ToddSeavey.