In a recent Splice article, fellow contributor Chris Beck shared his thoughts on intersectional feminism, and the threat he believes it poses to intellectual discourse, journalistic integrity, and women’s safety. Beck’s initial definition, “the core of intersectional feminism is the belief that oppressed people know more about life in general,” is simply wrong.

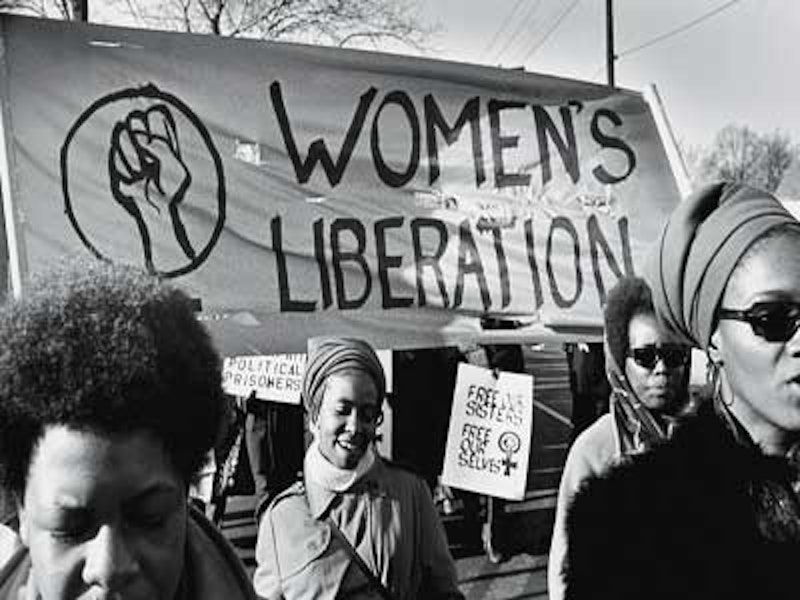

The true core of intersectional feminism is the unique discriminations faced by women of color because they’re at the intersection of race and gender. The term gained traction in the 1980s, based on the work of legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw while she was studying DeGraffenreid vs. General Motors. In this case, a group of black women in Detroit sued General Motors for employment discrimination, arguing “compound discrimination”—that they were being discriminated against for being both black and female. The court ruled that the presence of black men on the assembly line and white women in the secretarial pool didn’t amount to discrimination against black women. In her analysis, Crenshaw concluded, “…intersectionality was basically a metaphor to say they’ve got race discrimination coming from one direction, they’ve got gender discrimination coming from another direction and they’re colliding in their lives in ways that we really don’t anticipate and understand. So intersectionality is basically meant to help people think about the fact that discrimination can happen on the basis of several different factors at the same time. We need to have a language and an ability to see it in order to address it.”

While Crenshaw has welcomed the expanded definition of intersectionality to include lesbians, transgender women, the disabled, and various religious denominations, she has been consistent in keeping equal rights protections, usually from a legal standpoint, as the foundation of her work. In the 90s, sociologist Patricia Hill Collins filtered the expanded definition of intersectionality through Marxist feminism, and this, I believe, is what got us on the path to the unpleasant sort of feminism Beck is describing.

All social movements are prone to having a contingent of control freaks, especially feminism. In the suffragette era, there was an overlap with the temperance movement that led to prohibition. In the 1980s, there were the anti-porn feminists like Andrea Dworkin, who at their most extreme found a way to describe all sex between men and women to be of dubious consent. We have a new generation of control freaks, but I’m not clear about what they really want.

I find Beck’s subsequent argument regarding the focus on privilege creating an amoral worldview to be a strange one. I’ve already written my own piece on campus rape and journalism, but in the year since, I’ve noticed more of the discussion to be about “Jackie” and Emma Sulkowitz, and less about the reporters who failed in their diligence. There are guidelines in how to interview rape victims and report on sexual violence; the particular breakdowns came from the authors of those stories frontloading the articles with their own agendas, and also letting their subjects take control of the interviews to the point of interfering with the writers’ corroboration.

In Beck’s assessment of Western feminists ignoring the plight of women in Muslim majority countries, I think he’s more right than wrong, but I don’t think he’s getting the whole story. I actually like his using the anti-apartheid movement as a basis of comparison, if only because it gives me a straightforward basis of comparison. With apartheid, we were looking at one set of laws in the country of South Africa, and that was it. There are 50 Muslim majority countries, which means they all have their own set of laws. The good news is that there are feminist organizations in the Middle East like Sisters in Islam, and there are feminist organizations in the West like Women Under Siege reporting on a lot of what women are facing in the third world, or the Feminist Majority, that broke the story in the 1990s of how women are treated under the Taliban. Global human rights organizations like Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International do have a focus on women’s rights abuses, and the United Nations has UN Women to research and provide humanitarian aid to women around the world. The State Department has an Office of Global Women’s Issues to also research and provide humanitarian aid to women around the world.

The downside is that Beck is accurate in how blind too many American feminists are to women, not just in the Middle East, but in much of the developing world. One of the weirder things I’ve come across is when writers who are from the Muslim world, like Ayaan Hirsi Ali or Mona Eltahawy speak out on their experiences, they’re accused of fostering racism or colonialism. I think white American feminists are so wound up about racism and cultural relativism that they’re afraid to dish out constructive criticism even when it’s warranted. The end result is that this willful ignorance is putting women in peril.

While Beck cited the New Year’s Eve attacks on women in Cologne, Germany, there’s a broader argument to be made in regard to globalization. As people travel, migrate, and work all over the world, it's worth examining the effects of the gendered policies of Muslim countries. I’m referring to instances where women from Australia and Norway were jailed for adultery when they tried to report being raped when they worked in the United Arab Emirates. Western countries that’ve seen large influxes of Muslim immigrants now have OB/GYN scrambling to learn how to treat patients who have suffered female genital mutilation. Local social workers are also struggling to deal with young girls who have grown up in the West, who, just before hitting puberty, are sent back to the Old World on holiday, and return home victims of FGM. I think one of the better solutions has been Norway sending incoming immigrants to be educated about local laws and customs upon arrival.

Beck isn’t the first person I’ve seen take issue with Laurie Penny’s infamous tweet, but as a fellow white woman, I interpreted her words differently. People are usually raped by people they know, and people are usually best acquainted with members of their own race. Yet the rape that people tend to be the most concerned about is when white women are raped by black or brown men; violence perpetrated against women of color is too often overlooked. The absolute worst case scenario was the Emmanuel Church massacre last year, when white supremacist Dylann Roof said, “You are raping our women and taking over the country” as he shot nine black people at their Bible study. Another example that correlates with what Penny was referring to would be the Central Park Jogger case, where a white woman was brutally raped and beaten, and five young black men went to prison for what turned out to be the crime of one Hispanic man.

Beck’s “useful fools” observation is interesting, and probably not terribly different from a thought I’d had while watching hours of footage related to the protests following Milo Yiannopoulos’ speaking tour, in particular his joint appearance with Steven Crowder and Christina Hoff Sommers at UMass/Amherst. While watching the way they were heckled, I was reminded of the Two Minutes Hate scene in Nineteen Eighty-Four, where the citizens of a tyrannical dystopia are allowed some reprieve to go to the cinema and expel their anguish at the triggering images appear on the screen. The inevitable question is why so many young people are behaving like they live in a tyrannical dystopia when they don’t. I think the answer lies in the genuine problems they’re facing, like wage stagnation and the burden of student debt, and the mainstreaming of the idea that capitalism is the root of all evil. The end result becomes people believing they’re more oppressed than they are.

I don’t think intersectional feminism is the problem—at least not the original ideas espoused by Crenshaw. The real culprits are Marxists, control freaks who are eager to police language and mundane behavior, and a generation that has been discouraged from thinking critically, therefore reducing the movement to buzzwords and talking points. What bothers me is that feminism has been dragged away from a genuine sense of pragmatism, out of step with women’s everyday lives. I don’t dispute that white American women have it better than any group of women in history, but a few bugs in the system remain. The Equal Rights Amendment was never ratified, and I believe that following through on that would give more muscle to anti-discrimination laws, which would benefit all women.