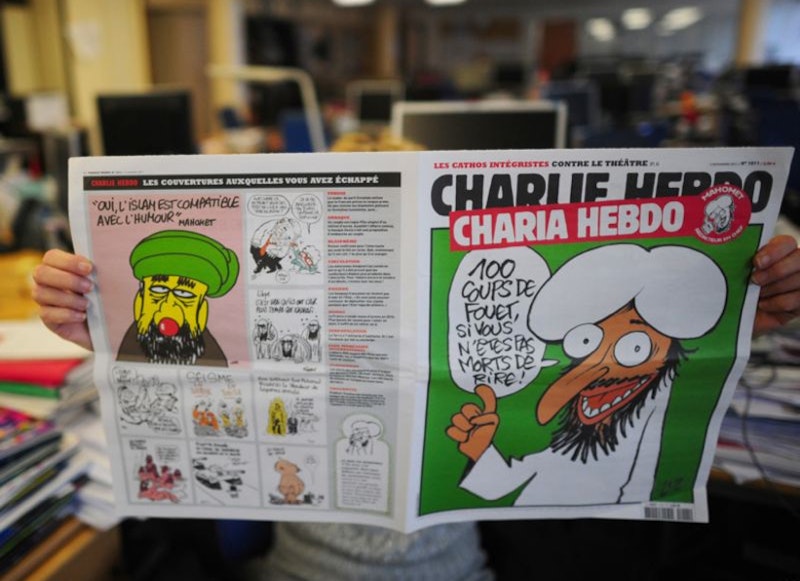

Stéphane Charbonnier wrote and drew the cartoon that turned me against Charlie Hebdo. It's tough to describe bigotry. We're used to seeing the disguised versions, the derivatives, and the raw product makes our eyes pop. But Charbonnier (his pen name was “Charb”) did it in every panel. He couldn't draw a Muslim who didn't look like a cretin with a banana plant hanging off his face. Or a Jew without a banana plant, this one slightly finned at the tip. Paging through Google, wondering at what I saw, I reached my turning point with a cartoon that had this word balloon: “1 million de rabais sur les 6, en échange de la Palestine!” Which means: “1 million off the six, in exchange for Palestine!” What six million? Well, this was a cover drawing, and the magazine's logo had been changed for the occasion, to Shoah Hebdo. And the character speaking was the Jew, who not only has a banana nose but payos and a black hat.

Nothing was off limits for Charlie Hebdo. That's good. But what you do when you go off limits—well, that counts. Charbonnier and his crew titillated readers with risqué pictures. These were attached to comments that—the political ones, anyway—appear to have been pretty inane. The pictures were more the point. The set-up resembles those stories reprinted in Heavy Metal, the ones that show young women ruminating in translated French while they search for their clothes. Jules Wolinski, another victim of the Paris massacre, did a cartoon offering the public-spirited view that the defense of Islam didn't depend on miserable losers like the terrorists. This truism was addressed to a banana-nosed creature with a turban. Now, you could take out the public-spirited sentiment and leave the banana nose, and you'd still have a Charlie Hebdo cartoon. They did that many, many times. But take out the banana nose? That was the bread and butter.

Charlie Hebdo attacked everybody, we're told. Pretty much. Because sometimes the titillation took the form of blaspheming things that the reader's grandparents cared about, such as Jesus and Mary. And sometimes it took the form of dumping on people for not being like the magazine's typical reader, for not being the usual kind of French. For being a Muslim or a Jew. Blasphemy and bigotry can give people a fun little thrill. The first doesn't matter to me, except insofar as I hate to see people's feelings get hurt over foolishness. But the second is very dicey, and the magazine's track record looks bad. They played for low stakes and made obvious moves. If you can't attack Israel without saying it's like the Nazis, you might as well give up.

But Charb and the rest are martyrs, and that's all most people want to know. We've forgotten that bigotry remains bigotry even if somebody has been shot. Anybody who points at the thing and says what it is, just follows the evidence of their eye and brain, gets marked as soft on terrorism. You're like the person who wants to know what the rape victim had on. Oh well. The thing about clichés is that they're never there when you need them. “I deplore what you say, but I'll defend to the death your right to say it.” That was always a good one, but now it's gone into hiding. I wish it would speak up.

What do we do with bigotry? We deplore it. And then, if some killers come around, we defend it. Because the next set of killers might kill somebody else, punish some other opinion. A crime like the Charlie Hebdo massacre lays a whole society open to attack. Even if your individual views don't bring retaliation, free agents with guns get to decide the limits of public debate. That's intolerable, and it’s the issue above issues when discussing the terrorist attack on cartoonists and office staff. But the other issues are still there. With all the attention being lavished on number one, we can spare some time for first things. Such as: defending and approving are not the same. Defending and deploring go together too. In fact, that combination is what marks off a liberal society. Find it and you're living someplace where people are free.

We are all Charlie. Too bad, but that's the way it is.