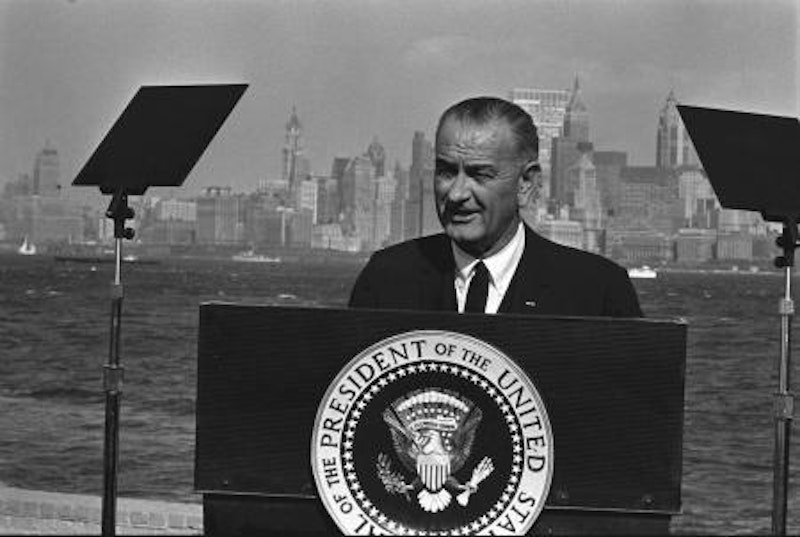

Each time an installment of Robert Caro’s masterful biography of Lyndon Baines Johnson drops in on the reading public, about once every dozen years or so, the question comes up: Why can’t succeeding presidents be as forceful and effective as LBJ was. And the answer is, after reading the fourth volume in the continuing series, that even Johnson probably couldn’t be as successful today as he was nearly a half century ago.

LBJ hasn’t or wouldn’t change. But times have. They involve a complex dystopia of money, special interests, the electronic news era, increased diversity, polarization and, above all, the disappearance of the towering figures, Democrats and Republicans alike, who served the nation alongside Johnson to produce a rush of truly remarkable legislation.

Even the idealized John F. Kennedy, remembered more for style than substance, fades in the shadows of Johnson’s accomplishments. Johnson, did, however, achieve much by building on Kennedy’s legacy and memory as well as those associated with the slain president.

What’s more, the political demographics as well as population shifts have changed almost unrecognizably over the past 50 years, in part because of the landmark civil rights legislation that Johnson enacted and foresaw as a politically divisive force but plunged ahead anyway. In those days, Republicans were the legendary liberal giants while the South was solidly conservative and Democratic. Today the reverse is true: The South is a regional Republican outpost and Democrats, for the most part, have planted their flag and staked their claim on the liberal (progressive, for the timid) side of the scorched earth. The two coasts are blue and everything in between is red.

Johnson’s 1964 civil rights legislation and the voting rights laws of 1965, along with Richard Nixon’s 1968 campaign’s “Southern strategy,” launched the upside-down conversion that, ironically, began with Republican Barry Goldwater in 1964 but was accelerated by Democrats on the side of civil rights. Goldwater would be ill at ease in today’s rigidly right-flank Republican party as would Johnson with today’s Democrats. It was Johnson, a Texas southerner by birth but a Roosevelt New Dealer by conviction, who said that he would push for civil rights legislation but warned that if it were enacted Democrats would never again carry the south.

Johnson was a force of nature by dint of his physical presence and his intimidating personality. He had that special touch, similar to that of Bill Clinton, of making everyone he needed actually feel needed, saying whatever needed to be said to accommodate the occasion or the person.

LBJ had a genius for “feel,” that is, an unerring instinct for what was needed by the people at any given time during his bracket of history and a certain direction on how to accomplish that goal. Who else would be so audacious as to declare a war on something as amorphous as poverty? But it is doubtful that Johnson’s hollering, haranguing, in-your-face lapel-grabbing and scatological cajoling would work in today’s media hothouse. Stephen Colbert, Jon Stewart and the late-night comics would create a laughable cartoon of Johnson’s lavatory hell-raising.

Johnson’s partners in the cloakrooms of Congress were not so much the ranking Southern Democrats whose interest was more in military spending more than in improving the lives of blacks. His helpmates were the Republican leaders of Congress—Sen. Everett Dirksen (R-IL) and Charles Halleck (R-IN) who helped to guide the civil rights bills through their hostile chambers. By contrast, today’s GOP leaders, Sen. Mitch McConnell (KY) and Rep. John Boehner (OH), along with the weasel-y Rep. Eric Cantor (R-VA), have one goal in mind—block everything President Obama attempts in order to blotch his record and destroy his presidency.

Johnson had the help, too, of the great urban Democratic leaders of the era—Mayor Richard Daley of Chicago, Gov. David Lawrence of Pennsylvania and Mayor William Green of Philadelphia—whose political machinery helped ease the way in elections as well as to help rally reluctant lawmakers on Capital Hill when key legislation was at stake. The big-city political machines are deader than Pterodactyls.

Nor did Johnson have to contend with the obscene amounts of money that are fertilizing today’s political campaigns, due mainly to the Supreme Court’s Citizens United decision which allows the free flow of unidentified funds into anonymous Super PACs and non-profit organizations. This year, for example, may produce two presidential campaigns spending a billion dollars each that are identified and equal amounts that are not.

To be sure, Johnson had his share of campaign money, as did Kennedy before him, much of it from Texas and from labor unions which have traditionally been among the largest contributors to Democratic campaigns. At the time, businesses were severely limited in their contributions to campaigns until the finance reforms that followed Watergate and established political action committees. Unions, since the Johnson era, have lost much of their membership and their clout.

The America of today is more of a mosaic of nations than the melting pot of Johnson’s era, due mainly to the immigration reforms of the 1960s that were sponsored by Sen. Edward M. Kennedy (D-MA). They slammed the door shut on Europe and opened it wide to Asia, the Middle East and Latin American countries, giving America a new coloration and new populations competing for recognition while striving to preserve their ethnic identities. The cohort of blacks and Latinos will soon overtake whites as the majority population in America.

Johnson had only to deal with whites and blacks. Obama must consider Muslims, Latinos (legal and illegal), Asians of many derivations, mid-Easterners with different languages and customs, political escapees from Africa and arrivals from nations that many Americans can’t even pronounce. The Cuban settlement in Florida, for example, is practically a nation unto itself. To wit: In times of international crisis, America is 9-1-1 to the world. Johnson had only Vietnam to contend with and it eventually drove him from office. And at the war’s end, hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese refugees were re-settled in the U.S. at the direction of Richard M. Nixon.

Special interests dominate the politics of Washington today. Their private preserve is the tax code, a 13,000-page collection of angles, loopholes and exemptions. In Johnson’s day, among the favorite baubles were the oil depletion allowance and the peanut import quotas. In fact, Johnson was able to rally reluctant Southern legislators to enact Medicare by raising the peanut import quota which was favorable to southern farmers. By today’s standards of lobbying for changes in the tax code, Johnson’s legerdemain was penny-ante. Most Republicans in Congress (and a few Democrats) seem to owe their allegiance not to the Constitution but to Grover Norquist and his anti-tax loyalty oath.

Second to the tax code are regulatory agencies, especially those monitoring pollution. Businesses and businessmen, such as the ubiquitous billionaire Koch brothers—as well as Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney and his vice presidential running-mate, Rep. Paul Ryan (R-WI)—want to unleash business to its robber baron ways by eliminating as many regulations and citizen protections as possible.

In the Johnson era, there were few, if any, environmental regulations. They only began to appear in the 1970s under Nixon and have spread rapidly since, one reason, among others, why American businesses choose to locate overseas. They can pollute other countries unchecked and unpunished and let the toxic clouds drift over the oceans to America.

Johnson, like presidents before and after him, loathed the press when it was dominated by newspapers. He’d often stomp through the press cabin on Air Force One and scowl at reporters whose work he resented and occasionally pinch a favored female reporter on her derrière, who’d squeal, “Oh, Mr. President!” At one ceremonial event attended by reporters, Johnson singled out The Baltimore Sun’s legendary Washington bureau chief, Phillip Potter. “Phil, you’re the only one who didn’t screw up today.” So there is a question of how Johnson would accept the new electronic era and the great bottomless maw of the 24-hour news cycle, the bullhorn of talk radio and the endless chase of Twitter-y gossip-as-news.

Johnson might be uncomfortable in the political and social environment of 2012. But not only was he a master of the legislative process but he was also skillful at rapid adjustments to situational politics, playing the emotional scale from grovel to grandeur. The broader question is: Could the electorate and the Congress of 2012 accept his overpowering style of governance. It is doubtful that he could budge today’s ideologues on the right.

Johnson, despite his accomplishments, made the major mistake of escalating the war in Viet Nam which Kennedy started. A favorite chant of anti-war demonstrators was, “Hey, hey, LBJ, how many kids have you killed today?”

He was challenged in 1968 by an anti-war candidate, Sen. Eugene McCarthy (D-MN), who ran second to Johnson in New Hampshire and scared Johnson out of the presidential race with a surprisingly strong showing. When the going got tough Johnson cut and ran.

The Democratic nomination eventually fell to Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey (D-MN), a former senator and one of the dominant liberal figures of the era. Johnson undercut the candidacy of his own vice president because Humphrey refused to endorse Johnson’s war in Vietnam. Johnson got even in that bittersweet way of his. He gave the nation the riots in Chicago and Nixon as president. Every president is an agent of his times and a misfit in others.

—Frank A. DeFilippo was a White House correspondent for the Hearst Newspapers in 1968 during the final year of Lyndon Baines Johnson’s presidency.