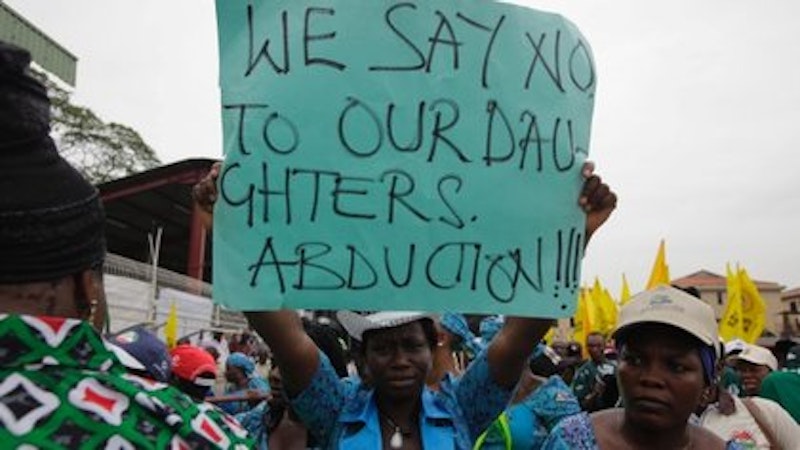

Two weeks ago, Islamic militants abducted more than 200 girls from a high school in northeastern Nigeria. The dramatic kidnapping, and the subsequent protests by Nigerians against their governments' inadequate response, has received a fair bit of coverage in the Western press (for example, here, here and here). Still, a number of commenters have complained that the story has not received enough attention. "Perhaps if the girls were on a ferry in Korea, a jet liner in the Indian Ocean, in the owner's box at a Clippers basketball game, or if they were white, we'd care more," Xeni Jardin wrote at Boing Boing, noting that at the time of her piece The New York Times had published only one reported story about the incident. Mary Elizabeth Williams at Salon speculated that the story might be "too remote" and added "Maybe it’s just that what goes on in a corner of Nigeria, however horrendous, doesn’t… make for sufficient page views and ratings."

The argument here is fairly straightforward: the Nigerian kidnapping is a major and traumatic news story. It's the sort of thing that, if the circumstances were right, could provoke a major media feeding frenzy in the West. The fact that it hasn't seems linked to American insularity and prejudice—to the fact that Nigeria is far away, that it’s not a major center of economic or strategic interest, and (as Jardin suggests) that the victims are black. As Williams acknowledges, America paying more attention to the kidnapping wouldn't necessarily "bring those girls back." But, she says, it might "put more pressure on the government to increase its efforts to find them." And, Williams argues, it might be a comfort to the parents "that they are not alone in their anger and pain."

It’s presumptuous to argue that people who have lost their children are going to be paying close attention to the frequency of headlines in the United States. Nigerian media is (as you'd expect) all over the story. Are our voices really so much more important than their voices that victims will get some sort of comfort from us that they aren't getting from their immediate neighbors?

Articles begging for more coverage of Nigeria also overlook a major truth of geopolitics: American empathy is really, really dangerous. American attention kills people. When U.S. news media and politicians start talking about how oppressed and desperate you are, people around the world know that it's time to duck and cover, because the bombs will be incoming.

Iraq remains the obvious case in point. Much of the argument for the 2003 invasion was based on empathy and on our supposed sympathy for the people who lived under Saddam Hussein's regime. Christopher Hitchens, for example, wrote that he supported the war because he was "a prisoner of what I actually do know about the permanent hell, and the permanent threat, of the Saddam regime"—a formulation which rhetorically placed him in emotional solidarity with those actually imprisoned and tortured by Hussein. Along the same line, David Horowitz back in 2004 praised the invasion of Iraq on humanitarian grounds. "In four years, George Bush has liberated nearly 50 million people in two Islamic countries. He has stopped the filling of mass graves and closed down the torture chambers of an oppressive regime. He has encouraged the Iraqis and the people of Afghanistan to begin a political process that give them rights they have not enjoyed in 5,000 years. How can one not support this war?" We invade because we care. We marched into Iraq in no small part because we empathized with those who were suffering in that country.

And what's the result of all that empathy? Violence in Iraq this month was worse than it has been since 2008; bombings and attacks meant to disrupt elections have killed 881 civilians, 52 policemen, and 76 soldiers. Overall, since the beginning of the war in 2003, Iraqbodycount estimates there have been somewhere in the neighborhood of 135,000 documented deaths. Others put the total at more than 500,000. American empathy certainly wasn't the only cause of those casualties—we also justified the invasion on the grounds of national interest and our own fear. But sympathy for the victims of Saddam was one important way we mobilized support for invasion. If people in the U.S. had managed not to care about Iraqis, many of those Iraqis wouldn't have died.

When people argue that we should pay more attention to Nigeria, or wherever, it’s worth thinking about what "more attention" has meant for people in Iraq, in Afghanistan, in Libya, and even in that supposed iconic humanitarian success Kosovo. If American news media really began covering the Nigerian kidnapping, what would that mean practically? Would we have John McCain making belligerent speeches about how we are all Nigerians? Would there be bluster and ultimatums and vague talk about military options being on the table? If the kidnapping were something Americans really cared about, that would mean that politicians would care about it too—and when American politicians really care, they often start reaching for their arsenal.

Empathy in world affairs is often presented as a good in itself; we should care about people in distant places because caring about people is what good people do. Putting ourselves in other's shoes advances the cause of peace and human rights—in theory. In practice, making decisions for people on the other side of the world based on a not-especially-informed estimate doesn’t always work out so well. To paraphrase Ronald Reagan, the most frightening words in the world are often, "We're the United States, and we care deeply about you." Our empathy is a threat. From that perspective, the greatest gift we can offer Nigeria, and the rest of the world, is our indifference.

—Follow Noah Berlatsky on Twitter: @hoodedu