Everyone has opinions.

According to the definition in my online dictionary, an opinion is:

- a belief or judgment that rests on grounds insufficient to produce complete certainty.

- a personal view, attitude, or appraisal.

The dictionary also helpfully provides a quote, from Friedrich Nietzsche: "One sticks to an opinion because he prides himself on having come to it on his own, and another because he has taken great pains to learn it and is proud to have grasped it: and so both do so out of vanity."

The word is from the Latin opinan, to think. An opinion is a thought, but not one based on fact. People will give their opinions freely without necessarily knowing the source. They think the source is in their own head. It is their opinion. They own it, like a piece of property. But when you question them, you discover they can’t tell you how they arrived at their opinion. They can’t tell you where it comes from, or the facts behind their opinion. Very often what facts they can cite are wrong.

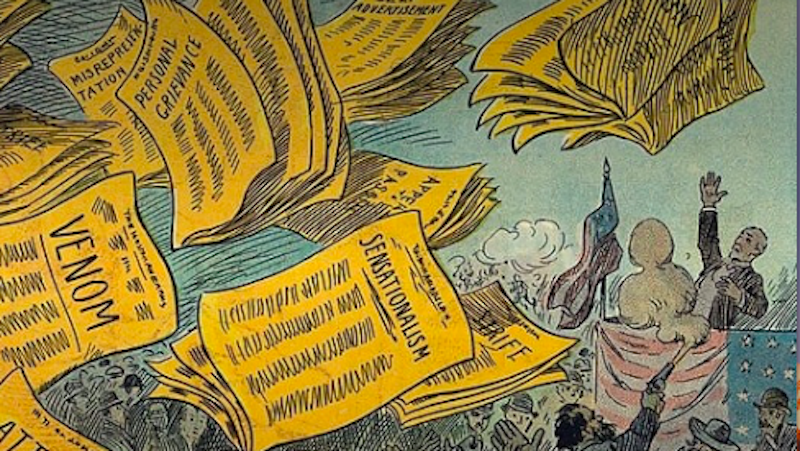

What’s more, you soon learn that almost everyone you speak to on any one topic has exactly the same opinion. The same thought exists in everyone’s head. So everyone has an opinion, everyone thinks it’s their opinion, and yet they share the opinion with everyone else. This is what’s referred to as Public Opinion.It’s like a virus: the mind-flu. Only it’s not an airborne virus which you catch when someone sneezes, it’s a thought-borne virus which you catch by listening to other people’s opinions. The problem with opinions is that, once having arrived at them, we think we know all there is about a situation, and that no further thought is required. We’re all guilty, progressives as well as conservatives.

People in the Public Relations Industry refer to themselves as “opinion makers.” They work through people they call opinion leaders. Opinion leaders are those who are able to influence other people in their thinking. Their job is to implant opinions into other people’s heads. The pioneer of the modern Public Relations Industry, Edward Bernays, said: "If we understand the mechanisms and motives of the group mind, it is now possible to control and regiment the masses according to our will without their knowing it... In almost every act of our daily lives, whether in the sphere of politics or business, in our social conduct or our ethical thinking, we are dominated by the relatively small number of persons ... who understand the mental processes and social patterns of the masses. It is they who pull the wires which control the public mind."

Even the term “public relations” is a public relations exercise. What Bernays meant was propaganda, but he recognized that the word had negative connotations, so invented the term “public relations” to cover it. An early success for Bernays’ newly conceived industry was a campaign to persuade women to smoke. This was in the 1920s. Bernays hired women to join in the Easter Sunday Parade of March 31, 1929, smoking what he called their “torches of freedom.” There was already a great social movement towards women’s emancipation but, by this managed public display, Bernays was able to link it to the idea of cigarette smoking. Smoking in public was interpreted as an act of personal and political emancipation.

You can see from this example that the industry is opportunistic and clever. The movement toward women’s emancipation already existed. Bernays’ achievement was to link this to a specific product. It was to take a thought that already existed and to turn it to commercial ends. Cigarettes became a symbol of individual emancipation. Women adopted the symbol en masse without realizing that they were being manipulated.

There’s an irony here. The more general an idea becomes, the more people will adopt it for themselves. The mass media’s success is that it makes an appeal to the individual. People use certain products to display their individuality. You hear people talking about their movies, their music, their food, their lifestyle, as if they really belonged to them. Advertisements for hair gel, for example, emphasize individuality. Individuality is contrasted with regimentation, while the product is used by millions of people. Millions of people all wearing the same hair gel, all doing so to be unique.

Likewise, people wear their opinions like hair gel. It’s a statement of individuality. I’m this kind of person, I’m that kind of person. We divide ourselves into tribes using our opinions. Once we discover what a person’s opinions are then we think we can assess them. We can dismiss or embrace them on the basis of their opinions. We don’t have to listen to them anymore. We check their opinions against our own to judge them. We’re like football supporters at a match, wearing our opinions like scarves around our necks to show which side we’re on.

The same techniques used to sell us hair gel or lifestyle options are also used to sell us war. Humans aren’t rational creatures. We don’t make judgments based on fact or reason. Rather we can be manipulated by emotion. The news is spun to create certain narratives. Sometimes the good guys turn into the bad guys, as in Iraq, where Saddam Hussein, once an ally, became an enemy overnight. Sometimes the bad guys turn into good guys, as Germany did after World War II, or Japan.

An example can be found during the first Gulf War of 1990-’91. It’s highly unlikely that Saddam Hussein would’ve undertaken the invasion of Kuwait without the permission of his United States allies, and documentary evidence from the time suggests this was true. The Iraqi president called the US ambassador April Glaspie to a meeting on July 25th, 1990, a few days before the invasion. He stated the reasons for his dispute with Kuwait and asked what the US response would be. The ambassador replied: “I have a direct instruction from the President to seek better relations with Iraq,” adding that: “We have no opinion on the Arab-Arab conflicts, like your border disagreement with Kuwait.” Saddam took this as tacit permission for his planned invasion and went ahead with it.

After the invasion the Kuwaiti government in exile hired a public relations firm, Hill & Knowlton, to handle their case before the American public. An organization was set up, Citizens for a Free Kuwait, which had its headquarters in the Kuwaiti embassy. A campaign was started to win public support for US involvement in a counter operation to take back Kuwait. This is where the famous Nayirah testimony came in.

Nayirah was a 15-year-old girl who appeared before United States Congressional Human Rights Caucus on October 10, 1990. She gave tearful testimony before the caucus, citing claims of atrocities by Iraqi soldiers. She said she volunteered to work in a hospital and that Iraqi soldiers had come in with guns to steal the equipment and that they’d taken babies out of the incubators and left them on the cold floor to die. It was an important piece of evidence and was repeated by news outlets throughout the world. There’s no doubt that it played a large part in swinging public opinion in favor of the war.

President Bush repeated the story at least 10 times in the following weeks. But it wasn’t true. “Nayirah” was the daughter of the Kuwaiti ambassador to the US, which wasn’t revealed at the time. She didn’t speak under oath and was undoubtedly coached in her testimony. The story had been concocted from various unconfirmed reports and given spectacular force by the acting abilities of a well-spoken, fluent 15-year-old. The technique is known as atrocity propaganda, and is as old as the propaganda system itself.

This is just one known case where a public relations firm has been involved in selling a war. It almost certainly happens, in some form or another, before every prospective war. Call it “public relations,” “propaganda” or “psy-ops,” it all amounts to the same thing: the manipulation of the narrative in order to justify aggressive action.

Every war needs a story. In Afghanistan in 2001 it was the presence on Afghan soil of Osama bin Laden, widely blamed for the 9/11 attacks. Before the Second Gulf War of 2003 it was Weapons of Mass Destruction. In Libya in 2011 it was reports of an impending massacre of civilians in the port city of Benghazi. No matter how often this process is repeated, we’re always convinced the story will turn out to be true. The use of advertising techniques, the repetition of simple three-word slogans and the assurance that this is an entirely new product, is enough to sway the public mind into acceptance of yet another war that is against its own best interests.