It all went by so quickly, but it was 500 years ago this year that Catholic saint Thomas More foisted the socialist notion of a Utopia upon us in his property-denouncing, freedom-bashing work by that title, one that has deformed politics ever since.

They’ll sometimes tell you in school that it was an anti-utopian novel, but that’s nonsense. It has a classic flimsy framing device for putting the whole idea at a safe arm’s length—you could get arrested for being too blatant in those days—but despite the conceit of the description of Utopia being offered by a traveling stranger, you can tell the author was in love with the idea.

Central planning, which ought to make free people recoil as much as the mention of kidnapping does, still warms the hearts of academics, activists, and politicians everywhere. And there are other ways to damage civilization. Humanity tries most of them eventually.

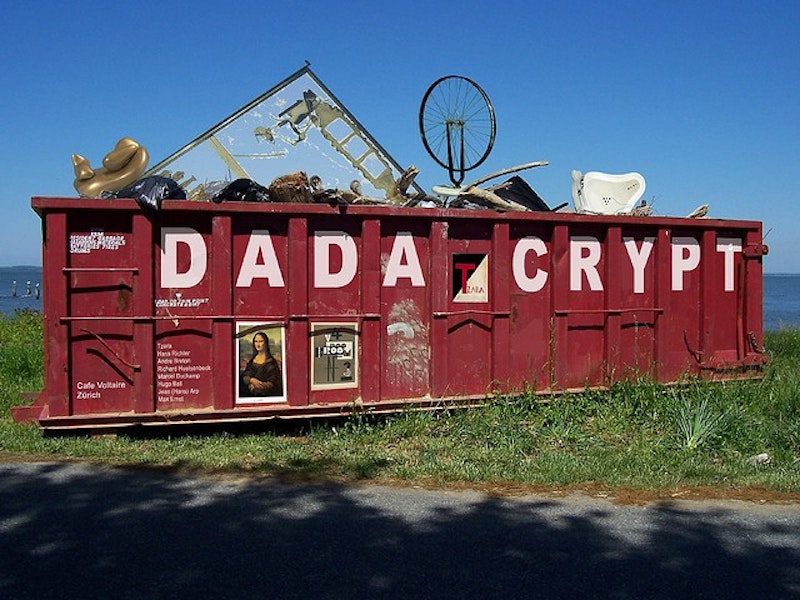

This year also marks the 100th anniversary (depending on how you mark the starting point) of the chaos-loving, logic-shredding, disorder-loving art movement known as Dadaism. You have to have some respect for Dadaism, which not only did a fine job of showing how absurd the purported rationality of early 20th-century society really was but provided a prophetic glimpse of the cut-and-paste, mash-up world of online comedy and neon plazas in which we now dwell.

Still, don’t take political advice from Dadaists. Most were far left and dreamt of putting into action fantasies such as Andre Breton’s antisocial dream of wandering into a crowd firing a pistol, an artist’s version of becoming the Joker.

I think we can all understand the opposing attractions of Utopia and Dada, Apollo and Dionysus, order and chaos—or in my mind when I was a child, perhaps Sam the Eagle and his fellow Muppet Gonzo, succeeded in college by the tension between utilitarianism and Nietzsche. Perhaps Kermit was the proper balance for kids, and libertarianism like that described in my book was the resolution I sought between collective utility and individual will.

But in the broader culture, both impulses are still with us. Just in the past few days, I witnessed downtown artists performing a scene from a reimagined version of Alfred Jarry’s absurdist play Ubu Roi and heard an uptown realtor explain that regulations forbid him even to tell apartment-seekers whether their prospective neighborhoods are high-crime or low-crime areas. Sane living—and happiness for most people—happens somewhere in between these unhinged and un-free extremes, now as it was in centuries past.

—Todd Seavey is the author of Libertarianism for Beginners.