President Donald Trump temporarily succeeded in barring CNN showboater Jim Acosta from the White House, which sparked furious cries that the First Amendment was under siege. He’s threatened to change libel laws to restrict media reporting on him, which is just talk, and personally mocked and attacked numerous members of the press. The President’s often called the single greatest threat to the First Amendment the nation’s ever faced. But the truth is that, while he’s an authoritarian by nature, he doesn’t doesn’t have the power to change media behavior in any significant way.

Trump’s not the first president to flog the media. In 1807, Thomas Jefferson, who’d championed the free press before he became president, wrote, “Nothing can now be believed which is seen in a newspaper. Truth itself becomes suspicious by being put into that polluted vehicle.” Compare that to Trump’s tweet, “FAKE NEWS media… makes up stories and 'sources.'” Jefferson had newspaper editors prosecuted for sedition, and his predecessor in office, John Adams, signed the Aliens and Sedition Acts that limited freedom of speech and of the press. Franklin D. Roosevelt, hero to liberals, once gave a reporter a dunce hat and told him to sit in the corner. At a press conference, he handed the Nazi Iron Cross to a reporter and asked him to award it to the New York Daily News’ John O’Donnell. Another liberal deity, Barack Obama, leaned heavily on the Espionage Act, leaving office with a dismal record on press freedom and access.

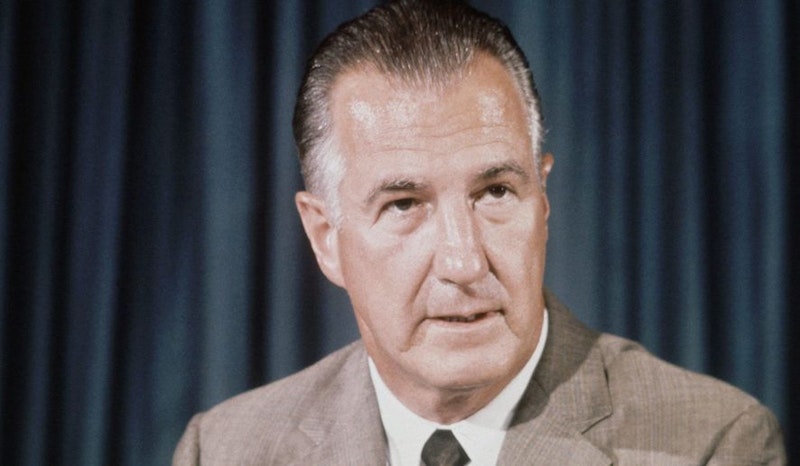

Richard Nixon, more than any other American president, was able to shape the behavior of the press, often via his “blunt instrument,” Vice President Spiro Agnew, who ventured forth into battle armed with incendiary speeches written by Pat Buchanan and William Safire, and vetted by Nixon. At the time, the media was generally considered to be neutral and trustworthy, but Nixon, who’d complained about the media for decades, sought to change that perception. They were hammering him daily on the Vietnam War, and picking apart his televised speeches with post-speech analysis, so he decided to go on the offensive. Agnew would speak of a dangerous concentration of power in the hands of a small group of privileged, unelected people. The views of this “tiny minority,” as he put it, “do not represent the views of America.”

Agnew’s series of alliterative addresses (e.g.” “hopeless, hysterical, hypochondriacs of history") aimed at the “silent majority,” began in Des Moines in 1969, where he gave a Buchanan-crafted speech that may be the most famous and influential speech ever made by a vice president. He spoke of the wide gap between how most people had received Nixon’s latest speech and the way the networks, with their “tiny and closed fraternity of privileged men,” analyzed it. His criticism of the media, he insisted, was not a call for censorship. As he saw it, the censorship was taking place inside the media—pro-Nixon views were being suppressed. To fix this, he called for democratic media reform.

Former President Lyndon Johnson told Agnew that it was unwise to take on the media, as it was a futile battle, but Middle America, which was sick of what’s now called “media bias,” ate it up. They flooded the White House and the networks with telegrams. While Agnew’s now commonly called one of the worst VPs in history, by the end of that year he was the third-most-admired man in the nation, trailing only Billy Graham and Nixon.

The Agnew strategy worked. The Vice President appeared on the cover of Time and Life magazines. Media corporations took stock of themselves. The New York Times, not used to being slammed by a high-level politician, decided to implement an op-ed page to incorporate diverse voices into its pages. Ironically, William Safire ended up appearing in it for 33 years. For a while at least, the networks stopped doing their “instant analysis” of presidential addresses that so irked Nixon. NBC News sent two reporters out on the road to do reporting from the heartland. Local news stations started looking for more soft news to replace critical analysis of the Nixon administration, beginning a trend that’s still currently in place.

Try as he might, Donald Trump can’t make the media respond to his charges of “fake news.” He faces an entirely different media landscape that’s already been immunized against such trash talk. When Agnew started doing it, with such colorful insults as “nattering nabobs of negativism,” he was breaking new ground, which gave his words impact. Decades later, after cable news and the Internet have contributed to devastating the media’s credibility, Trump’s merely reinforcing what his base already felt. While Agnew’s stinging criticism resonated outside of “movement” conservative circles on the Republican side, Trump’s barbs have little effect outside his base. The fact that Fox News often resembles state news doesn’t help him make his case of media bias against him either. Nixon and Agnew had no such cheerleaders in the media to watch their backs.

Agnew was a run-of-the-mill shakedown politician who took envelopes of cash in the White House, but he had the memorable words of Safire and Buchanan to drive his points home. Trump’s a grifter with a limited vocabulary who can barely string two coherent sentences together, rendering him unable to make subtle, nuanced critiques that could provoke thoughtful responses from the media. Try to imagine him saying what Agnew said: “A raised eyebrow, an inflection of the voice, a caustic remark dropped in the middle of a broadcast can raise doubts in a million minds about the veracity of a public official or the wisdom of a governmental policy.”

Spiro Agnew was an early prototype of Trump, something that’s mostly forgotten now. He was a harbinger of the modern Republican Party who knew how to appeal to non-college-educated, rural, white Americans long before Trump unveiled his particular form of nationalism/populism. Trump can mess around with Jim Acosta and talk about fake news, but Agnew already did the heavy lifting for him. He’d be pleased to see what his efforts have produced.