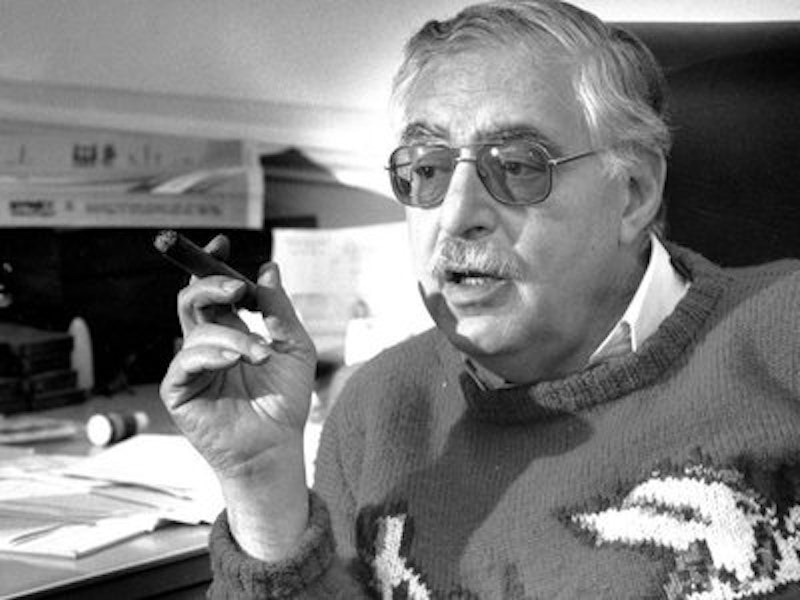

If the late world-renowned political consultant Joseph Napolitan were asked to offer one piece of advice to Donald Trump it’d be: “It’s impossible to be the candidate and campaign manager at the same time and the person who tries will fail at both.” That prophetic wisdom was among the primal lessons, tucked with 99 others, that Napolitan accumulated in his more than half century of counseling the mighty and the middling, from John F. Kennedy in 1960 to lowly city council candidates, in the dark and sometimes amoral art of winning elections. It is also the cause of Trump’s rapid decline and fall.

Napolitan assembled his selected lessons in a book, The Election Game, and in a kind of memo-to-self titled 100 Things I Have Learned in 30 Years of Political Consulting. They’re as much universal truths as political observations. First, let’s posit that Napolitan practically invented modern political consulting. If Machiavelli was the world’s first political consultant, Napolitan was surely the second. And next, for clarity’s sake, Napolitan wouldn’t be advising Trump because, as he’d stated often enough, “I only work for Democrats I like.”

But to keep the point and the argument flowing, Trump’s singular mistake has been to believe that he can manage himself. Trump’s a walking dilemma: scripted he pleases party leaders; unscripted he delights his supporters but displease party leaders and other rational beings. The result is campaign chaos. Trump doesn’t know what he’s doing or saying. Even more offensive is that Trump’s not very clever, though he may think he is.

That plays into Napolitan’s second lesson. “The right strategy can survive a mediocre campaign, but even a brilliant campaign is likely to fail if the strategy is wrong.” Trump has been unable to segue from his heady primary election performance in which he vanquished 16 rivals in what were basically local street fights, to the general election which is about big-picture issues and the main prize itself. He seems incapable of recognizing the difference. Simply put, Trump has no strategy. He has no campaign, either, except a private jet to get him from here to there. Which leads into one of Napolitan’s next droplets of wisdom: “The size of the crowds bears little relationship to the vote.” Trump regularly draws impressive crowds to his rallies, many loyal supporters, some just plain curious and others to protest. But getting those same crowds to the polls in November is another matter and another applied strategy that requires coordinated get-out-the-vote drives conducted by ground troops and phone banks along with mass media motivation. Social media alone won’t do the job. Trump has displayed none of those basic strategies. As an object lesson, Napolitan reflects back to the 1968 Nixon-Humphrey campaign: “One day Nixon toured Philadelphia; the crowds were enormous. Humphrey went through a few days later; the crowds were small. Humphrey won Philadelphia by 100,000 votes.” Moral: Attracting crowds is not the same as turning out the vote.

Another Napolitan memo point concerns polls. “Polls are essential but don’t be fooled by them,” counsels lesson number four. “The only practical reason to take a political poll is to obtain information that will help you win the election.” That was the political wisdom before the media got into the polling business and polls were strictly internal campaign documents. Today’s media polls seem more like self-fulfilling prophesies. Trump and Hillary Clinton were about even in the polls at the conclusion of the two national conventions. And now, at least a half dozen polls show Clinton opening sizeable leads of anywhere from 10-15 points. That’s much more than a post-convention bounce. And the widening gap is attributable largely to Trump’s mouth. Even the Libertarian candidate, Gary Johnson, has jumped to 12 percent, three points shy of the 15 percent he needs to qualify for the debates. And if that happens, the election becomes an entirely different equation.

Trump’s real troubles began when he picked a senseless fight with the Muslim parents of deceased Army Capt. Humayun Khan which dragged out for more than a week. Trump added to the fury when he refused to say he supported House Speaker Paul Ryan and Sen. John McCain in their campaigns for reelection (under pressure, Trump later relented and endorsed the two). Trump’s mistake with Khizr and Ghazala Khan, parents of the dead Army captain, was that if he felt compelled to say something he said the wrong thing. Khizr spoke at the Democratic National Convention and as a Muslim denounced Trump’s anti-immigration policy. Trump, in turn, attacked Khizr and criticized Ghazala for remaining silent by her husband’s side. Ghazala responded with an op-ed in The Washington Post and both husband and wife made themselves widely available for interviews and television talk shows. The fact that is being overlooked is that the Khans allowed themselves to become entangled in the political process, and if Trump had attacked Clinton for exploiting grieving parents to advance her political cause there never would have been an issue. Trump has no understanding of nuance.

Another of Napolitan’s timely lessons is: “Never underestimate the importance of a divided party.” The Republican party was divided three ways—establishment, evangelicals and tea party—even before Trump became a candidate and it’s even more divided now that Trump’s the nominee. Napolitan eerily recalls a campaign he worked on in the Dominican Republic where the “intraparty rift was so fierce that President Jorge Blanco himself voted against his own party’s candidate for president… and many supporters worked for the main opposition candidate.” For Trump, the news is similar and accelerating almost daily as Capital Letter Republicans are announcing their desertions and defections, in many cases to Clinton. And the alarm within the GOP is that Clinton is such a vulnerable candidate. (The Clinton campaign, as reported, is trying to drive a wedge into the already fractured GOP. They’ve launched a charm offensive to win over Republicans to accept Clinton as a plausible alternative for those who reject Trump as an unacceptable representative of their party.)

Lesson No. 19 in Napolitan’s tutorial is: “Make sure your candidate understands the issues.” Simply put, before this campaign is over, fact-checkers will have run out of Pinocchios because of the huge number they have awarded Trump for all of his falsehoods and misrepresentations. Trump’s most recent: His statement of fact that he actually saw film footage, shot by the Iranian government, of pallets of cash totaling $400 million being off-loaded from an unmarked plane at the release of American hostages. No one has found evidence that such a film exists. Trump later backed down, a rarity.

Lesson No. 27 is simply stated by Napolitan: “Try not to self-destruct.” Napolitan cites the example of Walter Mondale in 1984 promising that if he were elected he’d raise taxes. “Candidates manage to shoot themselves in the foot with astonishing regularity,” Napolitan says. If Napolitan were alive today (he died in 2013) he’d be muttering that about Trump almost daily. Build a wall partitioning Mexico? Deport 11 million Hispanics? Tear up trade agreements? Dismantle NATO? Ban Muslims? Napolitan would think not. To be fair, though, Trump for the last few days has tried to stick to a scripted message and remain on point. No telling how long that forced discipline will last.

And finally, lesson No. 30: “Youi may be able to polish a candidate but you really can’t change him.” Napolitan states: “I’ve seen candidates who have improved (and some who have gotten worse) in the course of campaigning, but I’ve never been involved with a candidate who really changed very much.” Trump has proven that he is an immovable object. The party has tried. His children have tried. His friends and supporters have tried. But Trump is his own man, his own brand, his own impenetrable universe. Trump’s campaign performance is reminiscent of the poem Invictus, “I am the master of my fate; I am the captain of my soul.” And the poet who wrote it, William Ernest Henley, committed suicide to prove his point.

Note: For anyone who’s interested in the entire document, Joseph Napolitan’s 100 things I have learned in 30 years as a political consultant is available online by tapping in “Napolitan’s Campaign Lessons.”