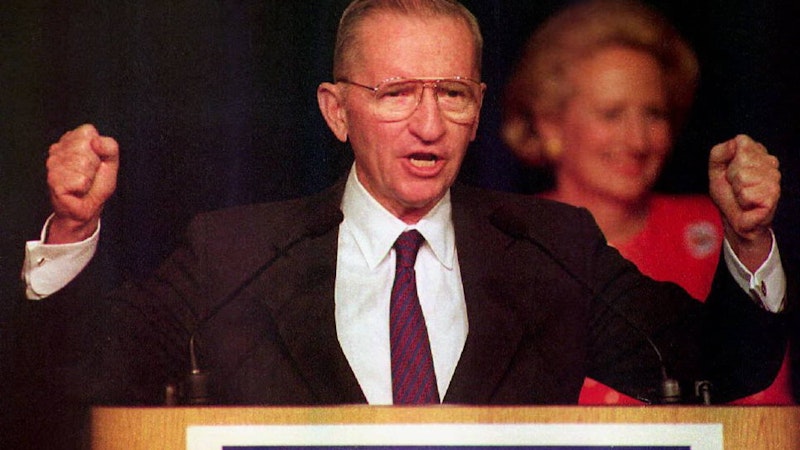

I was nonplussed to read an article in Politico stating: “Hours after announcing he wouldn’t endorse Donald Trump for president, Mike Pence huddled privately in Dallas with Texas moneymen such as former presidential candidate Ross Perot and the billionaire conservative Harlan Crow.” I double-checked that Perot was dead, then tweeted that point to Politico, which soon ran a correction noting that Pence had met with Ross Perot, Jr., which I’d suspected was the case when I’d seen the mistake.

As a fact-checker, I notice errors, a tendency not limited to work. I watched The Goering Catalog, a Magellan TV documentary about Hermann Goering’s looting of European art during World War II, a topic with which I’ve no particular familiarity (I once got on a jury in an art-world lawsuit based on my perceived lack of knowledge of art history). The film’s interesting, but I was disappointed to hear the narrator say that Adolf Hitler “appointed himself Chancellor” in January 1933, because, as makers of a documentary about Nazis should know, Weimar Republic President Paul von Hindenburg appointed him.

“There are Four Postelection Scenarios, and Not One Is Good,” a piece in The New Republic by Brynne Tannehill, tells us: “If Biden wins the election but Republicans maintain control of the House of Representatives, it is very likely that Speaker Mike Johnson will refuse to certify the election, invoking the Twelfth Amendment to decide the election.” One problem with this is there’ll be no “Speaker Mike Johnson” in January 2025 unless he wins a vote in the House for that position then, even if he manages to hold onto the job through the 2024 election, which isn’t assured. Moreover, the Speaker, whoever it is, can’t just “refuse to certify the election,” but would need action by both houses of Congress, made harder by a 2022 law tightening the process for objecting to states’ electoral-vote slates. Scenario-building is an approach I value, but it shouldn’t boil down to multiple worst-case scenarios.

I thought I’d made an error in my recent piece “Varieties of Evil” in stating that the leader of an online cult “is a 17-year-old Texan who was recently sentenced to 80 years in prison,” as had been reported in The Washington Post and elsewhere; my subsequent search through an inmate database showed him with a 20-year sentence, which the Texas Department of Corrections restated in an email. However, after subsequent discussions in which I contacted a Washington Post reporter, it turned out the 80-year sentence was correct (he was convicted on multiple counts, some running consecutively). For a while, I was wondering if Texas might mistakenly release the prisoner 60 years early, but now his inmate page shows his full sentence going to 2102. (I did err in suggesting he’s currently 17, his age when sentenced.)

Recently I tried to explain Hawking radiation to a quiz-bowl team I coach at my son’s school. I drew a diagram on a whiteboard showing a particle-antiparticle pair forming at the periphery of a black hole, with one particle sucked in and the other radiating outward. This is what I’d recalled from Stephen Hawking’s explanation of the phenomenon in A Brief History of Time. I saw an online article asserting that Hawking had misstated his own theory, giving a popular version that distorted what he’d published in technical papers. Next I saw an article in Nature that restated Hawking’s explanation as I’d originally understood it. The bottom line is, I don’t know what to believe about Hawking radiation.

In assessing the credibility of people, publications and organizations, I give weight to their willingness to acknowledge error or uncertainty. Carl Sagan emphasized that inclination as well: “One of the reasons for its success is that science has a built-in, error-correcting machinery at its very heart. Some may consider this an overbroad characterization, but to me every time we exercise self-criticism, every time we test our ideas against the outside world, we are doing science. When we are self-indulgent and uncritical, when we confuse hopes and facts, we slide into pseudoscience and superstition.”

The error-correcting machinery, however, is itself imperfect, or at least may take time to click into gear. In an excellent piece in The Atlantic, Tom Nichols, who has focused on defending experts against populists, discusses “When Experts Fail,” including missteps during the pandemic. He opens with an acknowledgement of his own: “When I first started writing about the public’s hostility toward expertise and established knowledge more than a decade ago, I predicted that any number of crises—including a pandemic—might be the moment that snaps the public back to its senses. I was wrong.”

—Follow Kenneth Silber on Threads: @kennethsilber