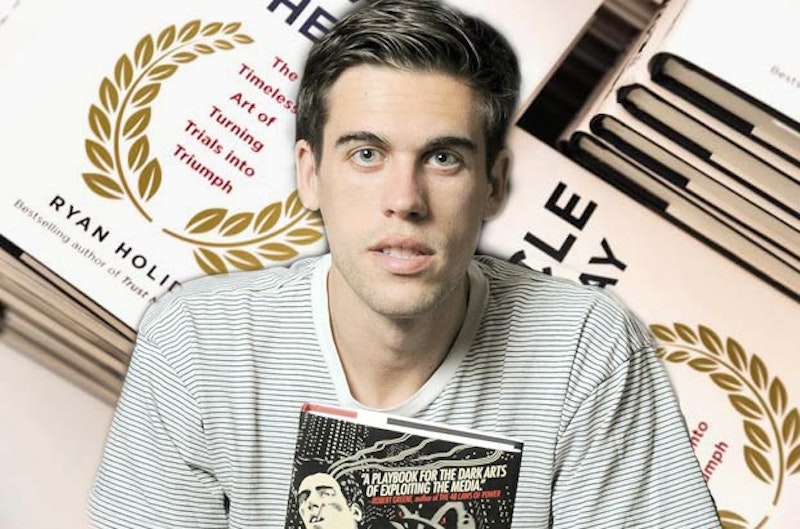

Ryan Holiday has been called a modern marketing genius, but in his own words, he is a “media manipulator.” If David Ogilvy is known as the father of advertising because of his meticulous research into consumer habits, then Holiday’s trademark is knowing how to tame the blogosphere. In his 2012 book, Trust Me, I’m Lying: Confessions of a Media Manipulator, he spells out how much brazen dishonesty one can get away with, and how it nearly ate him alive. Holiday wrote this as a quest for redemption, admitting in the introduction, “I am, to put it bluntly, a media manipulator—I’m paid to deceive. My job is to lie to the media so they can lie to you.” Holiday goes on to make the case that if cable news having 24 hours to fill has driven its standards downward, then the Internet’s infinite space is filled with bullshit. From lazy writers who copy verbatim from press releases to agenda-driven ideologues who latch onto anything to sell their narrative, it’s easy to spot how our fake news problem emerged. Beyond marketing and journalism, he also delves into the ways less scrupulous media manipulators can destroy people’s lives.

Holiday describes what he does as “trading up the chain.” He begins by seeking out smaller blogs desperate for a tip, which becomes a source story for a larger blog, which in turn becomes a story at mainstream media outlets: “Create the perception that the meme already exists and all the reporter… is doing is popularizing it. They rarely look past the first impressions.”

Blogs are desperate for clicks. By zeroing in on the most salacious aspects of a story, it’s a convenient way to drive traffic and not only get people to read the story but to see the ads supporting the blog. Holiday goes on to talk about how he’d also drive clicks by creating several pseudonyms and leave crazy comments all over the place, inciting people to respond, which would get them looking at the ads more than once.

In remembering that a click is a click, negative attention is still attention. Appealing to people’s anger is easy. In fact, “the most powerful predictor of what spreads online is anger.” If there’s one thing that I realized reading Holiday’s book, it’s that feminists are incredibly easy marks for marketing outrage and anger, and Jezebel, in particular, shows up repeatedly. Some of the more vivid plays come out during his tenure as marketing director for American Apparel, and promoting writer Tucker Max. Max’s tales of hard partying and promiscuity were sold as manifestos of decadence, and one of his most notorious marketing stunts was an attempt to donate to Planned Parenthood on the condition that they name a clinic after him. (They declined.) American Apparel’s back-to-basics style was sold with ads that went heavy on barely legal models (and occasional porn stars) posing suggestively in various states of undress. These stunts were tailor-made to stoke the feminist outrage machine, and they repeatedly fell for it, creating a blueprint for provocateurs to come.

To Holiday’s credit, he is bipartisan in his attacks, and doesn’t even spare Hollywood gossip blogs from his exposure. His Manipulator Hall of Fame includes Andrew Breitbart, Irin Carmon, James O’Keefe, Arianna Huffington, Nikki Finke, Henry Blodget, Michael Arrington, and Nick Denton, with entire chapters devoted to a few of these characters. Holiday cites an incident with Carmon that affected him directly, when she misinterpreted a recall of American Apparel’s nail polish, which eventually drove the manufacturer out of business. He describes Breitbart as able to manipulate “without the guilt,” which led to the selectively-edited video that cost former Department of Agriculture rural director Shirley Sherrod her job.

One of the things Holiday goes after is how some blogs pay their writers on a per-click model, which only encouraged them to crank out more sensational posts and save the fact-checking for only when they were forced to issue a correction. Holiday calls this model of post first, fact-check later “iterative journalism,” and credibly argues that it has brought us back to the age of yellow journalism. Among the parallels are hysterical headlines that overhype the content, overuse of pictures, fraudulent interviews, grandiose support for pet causes, and too many anonymous sources. Citing his research, he says, “Knowing the trademarks of yellow journalism from this era made it possible for me to know how to give blogs what they ‘want’ in this era.” The problem for journalists is that there really isn’t very much that’s newsworthy, but in order to drive clicks, spectacles need to be constantly invented. A recent example is MSNBC overhyping Rachel Maddow’s access to some basic information in Donald Trump’s 2005 tax return. It turned out to be one of Maddow’s highest-rated shows, in addition to the hours of Twitter attention the non-event received.

One of the more depressing aspects of iterative journalism is that corrections rarely have any effect. To go back to the nail polish story, the problem was that the glass bottles were too delicate, and broke under the stores’ halogen lights. When Jezebel ran the story about the recall, they assumed the breakage was because of toxic components, and didn’t contact Holiday until after posting. While they posted Holiday’s lengthy explanation, it was only with “updated” attached to the headline. The snowball effect resulted in the small, family-owned Long Island factory that American Apparel worked with to make the nail polish going out of business. In the ensuing lawsuits, the conclusion was that the recall issues could’ve been resolved if Jezebel hadn’t interfered. Holiday describes another shady practice as “the online shakedown.” It’s really a new version of extortion, and it’s a PR nightmare. While the demands are less overt, the implicit demand is that celebrities and companies had better play nice with bloggers (and possibly hackers) or else. Even Barack Obama knew the game: “If you take these blogs seriously, they’ll take you seriously.” Holiday describes the result as a culture of fear, where PR is as much about managing online nastiness as it is about promotion. For companies, consumer-oriented blogs have a particular sting, from people looking to weasel free stuff out of them, to wronged customers out for revenge. Some companies have begun running drills in the event of an outbreak of slander. Holiday argues that the paranoia is warranted, given an incident where a bogus post on Engadget briefly knocked down Apple’s stock price. Most companies, or people, can’t afford that kind of hit.

There were a few moments where I, as a writer, found myself feeling defensive. One was Holiday’s dissection of the “link economy,” where he accuses bloggers of, instead of using links for the intended purpose of citation, using links to pass the buck on their own half-assed research. In a section that breaks down buzzwords, I think he’s too cynical about writers using phrases like “according to...” and “said So-and-So.” Writers have to accurately cite their sources, we don’t like accusations of libel or plagiarism.

What keeps the blogs in business, despite all of their nonsense, is that we like the ego gratification of feeling smarter than the people who inform us. It’s a pity, since most readers haven’t cultivated the necessary skills to read past their own judgments. As Holiday explains, “Suppressing one’s instinct to interpret and speculate, until the totality of evidence arrives, is a skill that detectives and doctors train for years to develop. This is not something us regular humans are good at; in fact, we’re wired to do the opposite.”

I recommend Trust Me, I’m Lying to young people in particular. As the bad habits of the blogosphere bleed into mainstream journalism, I’m concerned that we may reach a point where we no longer know what honest media looks like. When everything is speculation, rumor, and half-truths, it becomes easy for charlatans and tyrants to ascend to power.