Usually, I rather enjoy Leon Wieseltier’s biweekly essays in The New Republic: there may be just another 100 people (plus Maureen Dowd) who agree, but I find his ponderous, mid- to late-20th century prose a welcome diversion from most of the stenography that passes for journalism in this modern world. Wieseltier is purposely provocative, and if his musings are out of synch with the current TNR, well, that hasn’t really changed since his literary editorship began there in 1983.

But Wieseltier’s Aug. 23 column “A Saint in the City," a blistering attack on New Yorker editor David Remnick for the sin of writing a 75,000 word profile of Bruce Springsteen a few weeks back is so off the mark I can only guess that world-weary Leon gave the article a mere glance. At least, that’s the charitable view. Accusing Remnick of contributing to the “literature of fandom,” and making “panting observation[s]” about the 62-year-old multimillionaire/populist rock star, Wieseltier proves his unworthiness of such criticism by claiming that The New Yorker story “could have been written by the record company.”

It’s an unfair condemnation. I agree with Wieseltier that Springsteen’s decline “has been obvious for decades,” and with the exception of two or three songs on his post-9/11 album The Rising, the last Springsteen song I’ve liked was “Lucky Town,” which was released in 1992. And so I approached Remnick’s short book-length profile with trepidation: he’s a wonderful writer and editor, but his hagiography of Barack Obama (The Bridge, Knopf) in 2010 was a rough read, and also a bit unseemly since his magazine was, and is, an enthusiastic booster of the President. Yet the article, “We Are Alive: Bruce Springsteen at Sixty-Two,” is not the pap turned out by Rolling Stone or similar publications that still worship at the veteran performer’s New Jersey mansion.

In fact, I’m not even sure Springsteen was all that crazy about Remnick’s exhaustively-researched profile—he interviewed countless past and present associates of the entertainer, traveled overseas to watch the man play, and details the miserable childhood of “The Boss” and his 30 years of seeing a shrink. In addition, Remnick writes about Springsteen’s ruthless style of management—he’s quick to fire people, with little or no remorse—and has his subject admit that he loves living “high on the hog.” This is not another recitation of Springsteen’s greatest hits: thankfully, hardly any of the man’s hundreds of songs are even mentioned, much less analyzed. Rather, it’s a story about aging: Remnick writes about the countless number of Springsteen’s friends and colleagues who’ve died—whether naturally or the result of substance abuse—and has his interviewee all but admit that time is running short, an unpleasant reality. Yes, Springsteen is fastidious about his health, working out and living fairly abstemiously (he’s supposedly never taken drugs), but as anyone of his age knows, he’s just one doctor’s diagnosis away from the last exit.

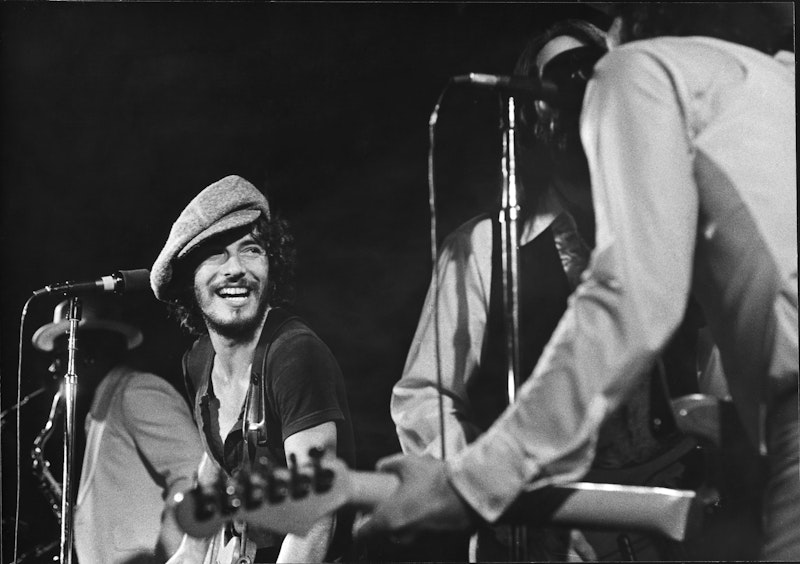

Like Remnick and Wieseltier, I saw Springsteen early in his career. In my case, it was pre-Born to Run: knocked out by his ’73 record The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle, I went to two concerts in early ’75, when you could arrive at the small venue on the night of the show and get a great seat. Remnick accidentally saw him earlier than that, when he and his friends inexplicably went to a Chicago show and Springsteen was the opening act; Wieseltier was present at two of his now-legendary Bottom Line shows in August of ’75.

I’ve had no desire to see Springsteen since, even though I thoroughly enjoyed songs (and still do) like “Atlantic City,” “Brilliant Disguise” and “Promised Land.” Oh, and here’s a Wieseltier whopper: “There is a bliss that only the sounds of one’s youth can provide. (For me, it’s been downhill since Dion.)” Please. Leon is 60, and unless he was truly and forever blissed out by “Teenager in Love” at the age of seven, that’s unnecessary hyperbole; I could claim it’s been “downhill” for me since Buddy Holly was killed, but it wouldn’t be true.

Wieseltier is correct, in his conclusion, that Springsteen is a safe icon, as “protest songs become entertainment for the rich, and Springsteen the idol of the elite.” And he had me chuckling by saying that Springsteen is now “Howard Zinn with a guitar.” Nevertheless, it’s unfair to slam Remnick as a groupie: a fan, certainly, but his absorbing profile is akin to Martin Scorsese’s documentary about Bob Dylan, No Direction Home. (Even if, in that case, Dylan was really the director, with Scorsese brought on for a bit extra star power.)

Wieseltier isn’t the only critic to mock Remnick for “We Are Alive,” but he’s still flat-out wrong.