He returned to the land as a president among the Society of Friends. He returned to the land of his people, with his people, alongside family and friends. He returned to the land as a peacemaker, after years of upheaval and the continuation of peace with other means.

The return was not, however, the end of Richard Nixon’s life in the arena. Not after his last night in the White House, or during the fall—in the autumn of the lifetime of his administration—when he saved the world from nuclear war. Not after he left the White House on August 9, 1974, or in the decades since the end of his life, because his words live on and his accomplishments endure.

The return was a beginning, giving Nixon purpose and his critics the distance necessary to judge him without malice.

The return began with a farewell from the East Room of the White House, ending the greatest comeback among Republican presidents since the election of the first Republican president.

Nixon spoke the language of his faith, with reverence for the light of the world, as he spoke about a young man—a young lawyer in New York—who said the light had left his life forever.

Blinded by the simultaneous giving and taking of life, of the birth of his first child and the death of his wife from childbirth, the young man marked the date with an X.

Thirty-six hours after the birth of his daughter on February 12, 1884, the young man’s mother and wife died on the same day, Valentine’s Day, the date of his engagement anniversary.

The shortest month was the cruelest month in this man’s life, marking the sixth anniversary of his father’s death and the loss of his namesake.

In naming his daughter after her mother, the young man memorialized his late wife.

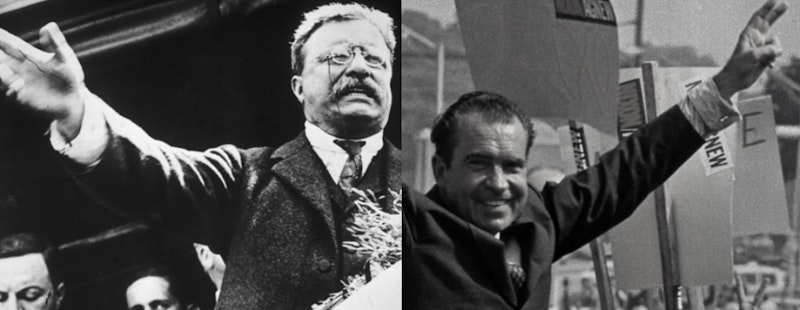

Beyond this act, the young man did not foresee the lights of fate and service, that he would become the nation’s youngest president and a light unto the nation, that what historians would memorialize on paper, sculptors would carve in stone, that the face of Theodore Roosevelt—his image cast in granite—would join the faces of Washington, Jefferson, and Lincoln on Mount Rushmore.

Nixon spoke with fondness for the first president known by his initials, seeing in T.R. a model for RN, despite the irony of Nixon’s use of the Wilson desk, behind which the 37th president spoke for the 37th and final time on August 8, 1974, or the time when Nixon said, “Fifty years ago, in this room, and at this very desk, President Woodrow Wilson spoke words which caught the imagination of a war-weary world.”

Forty-eight years ago, Nixon spoke the truest words.

He said we come from many faiths, that the One to whom we pray—the oneness we find in faith—is the same.

He said we pray to the same God in a sense, whose light sustains us, because only if you have been in the deepest valley can you ever know how magnificent it is to be on the highest mountain.