The Argentine writer, Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986) never wrote anything long, yet he was one of the most prolific writers who composed thousands of pages that covered many subjects and genres.

When Orson Welles’ first feature-length and studio produced film came out, Borges wrote a typically short review of it. Citizen Kane (1941) made an indelible mark on the American consciousness and has elicited both praise and criticism. Borges’ review of Citizen Kane is anything but typical. He’s not a “critic” or a “film reviewer” that we understand by today’s standards. In almost everything Borges has written, there are traces of philosophy, particularly metaphysics. Commenting on Welles’ film, we experience the great sensation of Borges’ continuous philosophical and theological endeavor.

Borges called Citizen Kane “an overwhelming film,” but we have to be careful not to assume that Borges means this negatively. An overwhelming feeling might signal a moment of revelation and unraveling of our interior being.

Although he considered some parts of the film “pointlessly banal,” namely the simplistic plot that involves Charles Foster Kane’s appetite for possessing everything and everyone, Borges finds metaphysical depth in it. It’s the “second plot,” as Borges puts it, that reveals something incredibly “superior” and superb about the film and Welles himself. He writes that Citizen Kane “links Koheleth to the memory of another nihilist, Franz Kafka. A kind of metaphysical detective story, its subject (both psychological and allegorical) is the investigation of a man’s inner self, through the works he has wrought, the words he has spoken, the many lives he has ruined.”

This is an intriguing and unusual description of Welles’ cinematic endeavor, yet completely true and authentic. Borges is referring to “Koheleth,” one of the books of the Hebrew Bible, also known as Ecclesiastes. It’s a depressing book. The author or authors are unknown, and the book doesn’t offer any practical advice on life. Rather, the author reflects on the futility of life. As the Biblical scholar, Robert Alter, points out, the author invites us to “contemplate the cyclical nature of reality and of human experience, the fleeting duration of all that we cherish, the brevity of life, and the inexorability of death, which levels all things.”

The very first verses of this Hebrew book immediately alerts us to what will follow:

Merest breath, said Qohelet, merest breath. All is mere breath.

What gain is there for man in all his toil that he toils under the sun.

A generation goes and a generation comes, but the earth endures forever.

…That which was is that which will be, and that which was done is that which will be done, and there is nothing new under the sun.

Borges may not have been a theologian by profession but his writing is imbued by man’s search for God and meaning. Welles was certainly not a theologian either but his films are infused with philosophical reflections on our quest for meaning and happiness. This is a theme that continues to develop in Welles’ oeuvre and Borges is correct to describe Citizen Kane in such a way. After all, what is Charles Foster Kane running toward or away from? Does he not understand that no matter how large and opulent Xanadu may have become, he will face the inevitability of death?

There’s a second component to this characterization that Borges offers, linking Kafka to Welles (in 1962, Welles filmed a loose adaptation of Kafka’s novel, The Trial). This is a curious description but once again, not so far-fetched. The futility and a constant rush to become the man he doesn’t want to be, Kane is the embodiment of Kafka’s world. He enters the realm of absurdity time and time again, proving that his actions, no matter how large, shocking, and other-worldly are empty attempts at control, that life is nothing but an illusion, and that we will rest uneasy in that illusion if we keep avoiding gazing at our face in the mirror.

Borges calls Citizen Kane a “metaphysical detective story,” and he ‘s correct to make such an assertion. Welles begins the film with Kane’s death, and because of this it would appear that we are moving backwards in time only. But this is an illusion. Welles also presents the film in continuous fragments, broken up by Kane’s own impending personal doom and brokenness. We struggle to reconstruct these parts of Kane because we want to solve the mystery of his public and private self, yet we’re also driven by an intense dislike of this man who’s overly ambitious (a seemingly good quality) but unwilling to search for his own interiority.

Does the mystery ever get solved? On the surface, (something, which Borges recognizes and acknowledges), the mystery of Kane lies in that first and final word, “Rosebud.” Certainly, it relates to the forgotten depths of a child that’s no longer there. The man and the child shall never meet, even though the yearning for such a chance encounter never ceases.

On a deeper level, this reconstruction of Kane’s character is a thankless task. It’s futile (as Qohelet tells us) precisely because of the fragmentary absurdity and nihilism (as Kafka tells us) of Kane’s existence. Borges points out that there are “forms of multiplicity” and that the “fragments are not governed by any secret unity: the detested Charles Foster Kane is a simulacrum, a chaos of appearances.” There’s no difference between Kane’s personhood and persona because he never allows himself to be vulnerable to himself or others. Welles shows this superbly in every frame: the larger the persona of Kane is, the smaller his interiority becomes. As the metaphysical masks duplicate, Kane’s face is entirely disappearing. Looking in the mirror brings only anguish and self-hatred. As Borges writes, “The hero observes that nothing is so frightening as a labyrinth with no center. This film is precisely that labyrinth.”

It’s hardly surprising that Borges saw these elements in Citizen Kane with such clarity of a writer and a philosopher. Throughout most of his fiction, he’s obsessed with mirrors and labyrinths. They represent the ever-present tension inherent in every human being that rarely gets resolved. In his story, “The Draped Mirrors,” he writes:

As a child, I felt before large mirrors that same horror of a spectral duplication or multiplication of reality. Their infallible and continuous functioning, their pursuit of my actions, their cosmic pantomime, were uncanny then, whenever it began to grow dark. One of my persistent prayers to God and my guardian angel was that I not dream about mirrors. I know I watched them with misgivings. Sometimes I feared that they might begin to deviate from reality; other times I was afraid of seeing there my own face, disfigured by strange calamities.

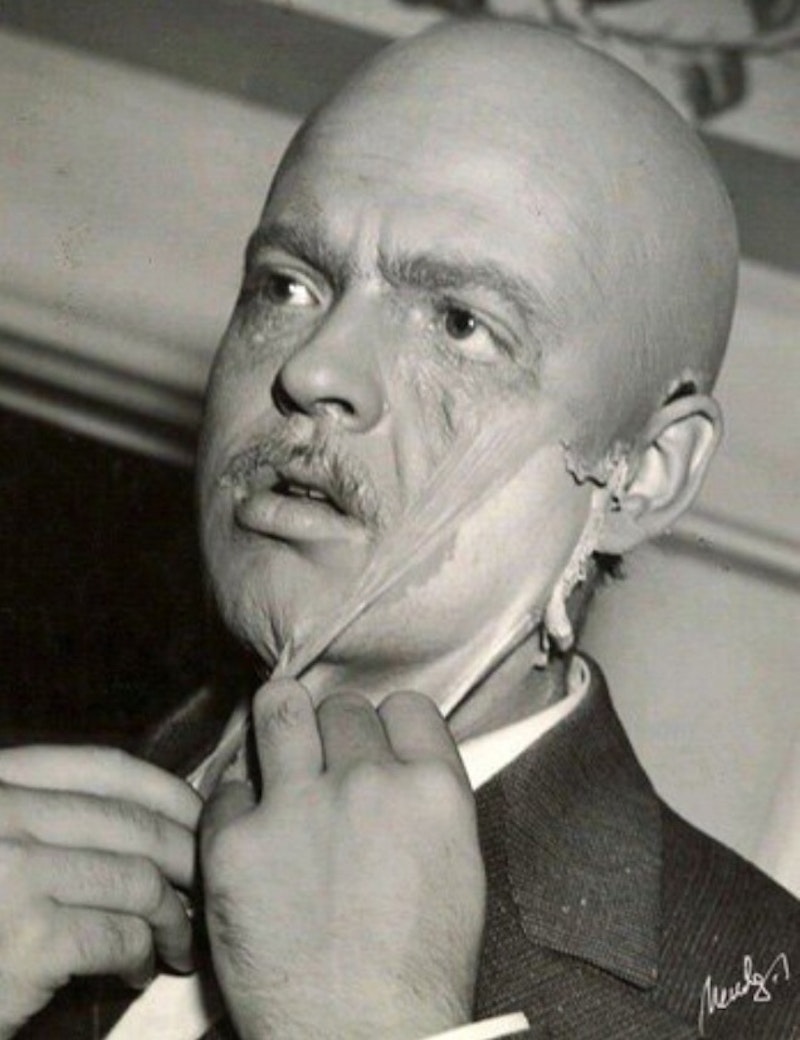

Welles was not explicitly a philosophical filmmaker. Nevertheless, the themes in his films always deal with moral and ethical problems, as well as reality and illusion, and certainly with labyrinthine mirrors, the clearest examples are Citizen Kane and The Lady from Shanghai (1947). Ever the magician, Welles presents both appearances and reality with an artist’s certainty, yet our certainty of what’s real and what’s fake diminishes in our minds. Continuously, and at times, unbearably, Welles thrusts the mirror in front of our faces in order to confront the labyrinths of our own minds.