Somehow, John McCain’s anxiety-inducing hotheadedness and overtly aggressive foreign policy don’t translate into an exciting speechmaker. Listening to one of his speeches brings out an inner five-year-old, creating the urge to say, “Mommy, I don’t wanna watch the news anymore. I’m bored. This is stupid. Put on Nick!” But I’m getting my wisdom teeth out today and will have no choice but to glaze over and watch constant reruns of McCain’s pale face for the next week. It’s either that or baseball, and frankly, the Orioles’ play as of late is probably less palatable than McCain.

Right now, the fear of being hopelessly bored—though there’s still hope for more hilarious Palin scandals—is competing with an irrational fear of dying during surgery to combine into one super-annoying fear. Too many people have relayed surgery horror stories: an allergic reaction to anesthesia killing a friend of a friend of a friend. Oh, and that girl whose surgeon accidentally left cotton in the back of her mouth, suffocating her while she maintained just enough consciousness to know, but not enough to scream.

Well, if this is my last article, then I’m ready. At some point we all have to confront death and mortality in our lives, and I did it when I was about nine. There I was, trudging through the forest behind my great aunt and uncle’s home in Vermont. The Mad River runs behind that house, racing through the cracks in the ice during the winter and lollygagging by in the summer. Stamping around the river back there, finding sections just barely deep enough to swim was one of my favorite pastimes.

That year, though, Vermont had a particularly long and snowy winter. Massive amounts of recently melted snow had flowed into the river. Adding to that, it had rained almost every day of the week before we came to visit. This was not the normal Mad River babbling over my tiny ankles; instead it thundered over the smooth large rocks that made up the riverbed. Being a rather stubborn, reckless child, I still had to go in.

But from the first step, I realized I might have made a mistake. My initial daydreams of pleasant swimming instantly melted into the hypothermic ex-snow that was rushing up to my knees. Reality set in. But I had to cross. I could see the other side. I had already made it a third of the way, and it seemed so close.

Each step was carefully plotted like a chess move. The rocks were so smooth, so slippery. Every movement toward the center of the river became a test, moving my legs through what felt like quicksand, pulling me, impeding my journey. As I drifted past the center of the raging river, a sense of accomplishment began creeping up in the back of my head. I had done it. I had made it through the test, and the rest was smooth sailing. All that was left was get to the other side, sit on the bank, wave to my parents, and deliver that wonderful gloating “I-told-you-I-could-do-it” smile. By this point, the water was halfway up my torso, making its way to my shoulders.

Maybe it was poor footing. Maybe it was a rock that was slicker than anticipated. But either way, the current was too much for me, and mid-step, it bowled me over. I remember watching my dad on the river bank, panicking, sprinting downstream after me. The water was so much faster than even my dad could run. I bobbed under and over, under and over. It was cold, but not in the painful, knives-all-over way, but in that numbing, eerily calming way. As I raced along, I got used to the motion and the feeling of helplessness. I let the river take me for its ride. I began to think about the waterfall that I knew was about a quarter-mile ahead. I thought about the sharp rocks I started to notice flashing past my water-blurred vision. I realized that this could be it. After nine short years, I was going to be the kid who died in a river.

Almost dying produces a very particular reaction, and when I was in a car accident nearly seven years later, the exact same thing happened. You drift outside of yourself and watch the whole story unfold slowly. You see yourself drifting—not racing—down the river, taking what could be your final deep breaths. There’s a sense of submissive calm. You’ve accepted it. Everything is okay. Your whole life is summed up in that feeling, and you can see everything that’s ever happened without being able to see anything at all. Then, you hit a giant rock, standing like a pillar from God in the middle of the river. You hit it at just the right angle, and it has just a flat, rough enough face to catch you in its hands. You are saved.

I hit the rock with a thud in the middle of my back. My father caught up and ran in after me. I was brought inside the house where I was afforded the rare privilege of using the master bathroom. I sat in the massive bathtub and could still see the river from my bathtub vantage point with its massive window looking into the backyard. I wasn’t angry at the river—it was just being itself, after all. It was just a thing that happened. If I die during surgery, it is just a thing that happens. All statistics are in my favor.

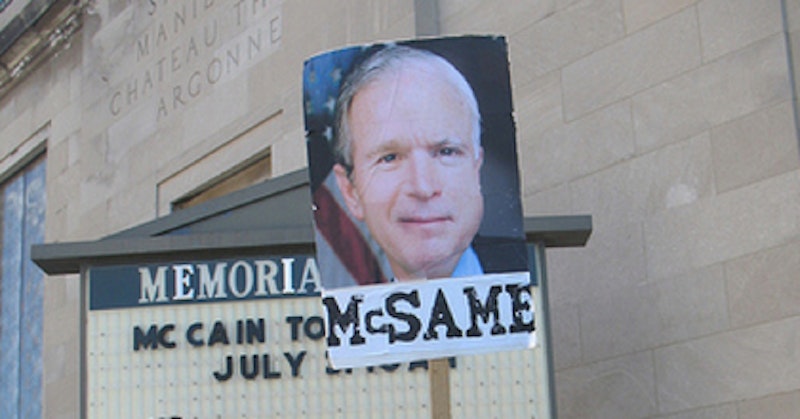

At nine, I saw what I wish everyone could see and understand, even if I didn’t know how to explain it. Look, four years ago, a Thing Happened. But in two months, we need to stop and take a look at ourselves. As a nation, we’re just like that little kid staring at the river, still shivering in the bathtub. We’re staring at a white guy from the southwest, severely lacking in oratorical skill, messing up his facts, and tacking way hard to the right. I know many of us want to get right back into the river, prove their bravery and their faith in the justification for going in that first time.

So as John McCain slowly abandons everything that distinguished him as a moderate Not-George-Bush—his new embrace of social conservatism with the choice of Sarah Palin, his votes against extending carbon emission tax credits and push for offshore drilling, his increased support for Bush’s tax cuts—just try to be that kid. In two months, when you’re standing in a voting box, don’t get us back into the Mad River like before. If you have to, just wait four years, until at least the tide has gone down.

The Freezing-Death Candidate

Let’s learn from our voting mistakes, shall we?

Photo by aflcio2008.