Ex-49ers QB Colin Kaepernick’s back in the news again, now that the Washington Redskins declined to give him a call after their quarterback, Alex Smith, suffered a season-ending leg injury. People are again grousing that the NFL doesn’t respect his First Amendment right to take a knee during the national anthem, but the NFL’s a private entity that the First Amendment doesn’t apply to. Plenty of others have similar complaints—especially after someone gets banned—about social media platforms, but they’re in the same category as the NFL. The First Amendment is both the most important and the most misunderstood constitutional amendment.

It’s annoying that so many Americans who don’t understand that the First Amendment applies only to governmental restrictions on free expression feel free to weigh in on the issue anyway. They should read it: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”

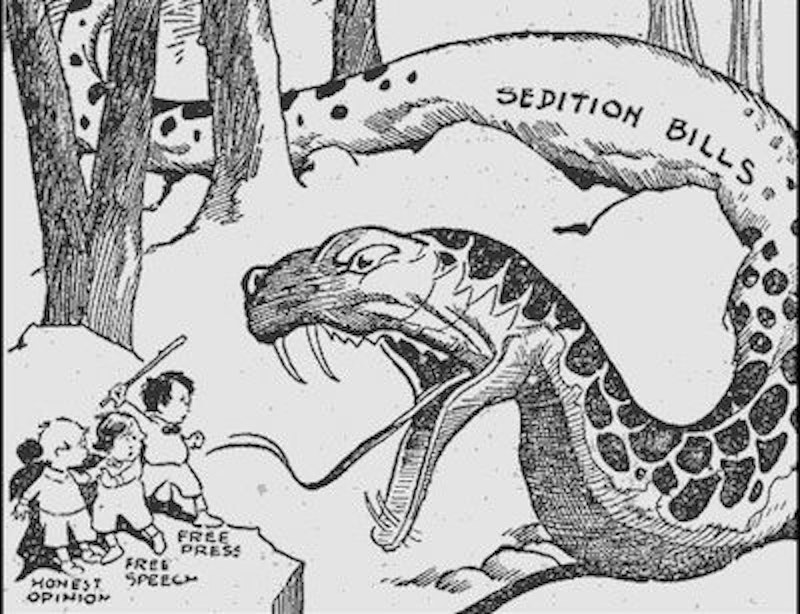

The First Amendment is at the core of American identity. Ask a citizen what it’s like to be American and they’ll most likely tell you that it means you can say whatever you want to. There’s a good chance they think that’s the way it’s always been, but in 1798 John Adams, wishing to suppress the Jeffersonians of the Party who were criticizing his administration, signed the Sedition Act, which made it a crime to mock or denigrate the president, Congress, or the government of the United States. While the Sedition Act never made it to the Supreme Court, lower courts ruled that was consistent with the First Amendment. The First Amendment got off to a shaky start because the Founding Fathers, having never lived in a society that allowed for freedom of speech, had no clear understanding of the issue. A long process of evolution was required to get to where we currently are on limiting the government’s power over free expression.

When Jefferson became president he made restitution to all those convicted under the Sedition Act, the first major action in that evolutionary process. The Supreme Court didn’t get too involved in the process until the early part of the 20th century. In writing the 1919 decision for the landmark Schenck v the United States case, Associate Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes introduced the concept of "clear and present danger" (which in this case was WWI) as a justification for placing limitations on free speech. The Court upheld the wartime conviction, under the Espionage Act, of Charles Schenck, who’d been urging men to resist the draft with a leaflet that the Court ruled would normally be protected speech during peacetime. Holmes wrote that what Schenck had done was the equivalent of shouting fire in a crowded theater.

Shortly thereafter, Holmes reversed his position in an eloquent dissenting opinion for case of Abrams v. United States, which upheld the conviction of a socialist advocating a general strike in factories producing military goods. Holmes argued that a direct and imminent connection between an expressed opinion and a subsequent crime had to be established in order to constitutionally curtail an act of speech. Jacob Abrams had been convicted for distributing pamphlets, but Holmes wrote that he doubted that "the surreptitious publishing of a silly leaflet by an unknown man... would present any immediate danger."

The Supreme Court would continue to rely on Holmes “clear and present danger” standard for 50 more years until the Brandenberg v Ohio decision in 1969 established that speech advocating illegal conduct was protected by the First Amendment unless it was likely to produce “imminent lawless action,” a sentiment that reflected Holmes’ dissent in Abrams v the United States. In reversing the conviction of Clarence Brandenberg, who’d made anti-Semitic and anti-black statements, and had explicitly called for violence against desegregation advocates while addressing a KKK rally, the Court established that what’s now called “hate speech” is constitutionally protected.

The Brandenburg decision remains the legal standard for evaluating incendiary speech. Compare its sparse limitations on freedom of expression to the situation in the U.K., which has no constitutional protection of free speech. British police have notified citizens that they may pay a visit to their homes if they’re not “kind” to others online. They’ve also investigated former foreign secretary Boris Johnson over a joke he made about women who wear burkas.

The woeful U.K. approach to free speech is a reflection of the fact that, while many people will tell you free speech is great, their natural impulse is often to reject it, especially in cases where it’s offensive or appears to be persuasive enough to be dangerous. Throughout American history, the courts have intervened after lawmakers went overboard in restricting free speech for these two reasons. British citizens, lacking codified protection of free speech and used to giving up individual rights for a feeling of safety, now find that law enforcement can police the kind of jokes they tell and the way they argue political matters online.

The younger generation in the U.S. has been raised to be certain they have the right to be emotionally safe without being taught about the struggle it took to achieve a society that enjoys an unprecedented level of free speech. They’re temperamentally disposed to accept the U.K. model that so empowers the police. The regressive Left, which doesn’t care for former Supreme Court justice Louis Brandeis’ dictum that the remedy for evil speech is “more speech, not enforced silence,” provides further pressure against the high threshold that the Brandenburg decision set for restricting speech. They want “hate speech,” which they’ll define, to be illegal. Words are actions, they tell us, and actions can be legally limited by the government. What they neglect to say is that, if they had their way, they’d misuse hate-speech laws to stifle dissenting viewpoints.