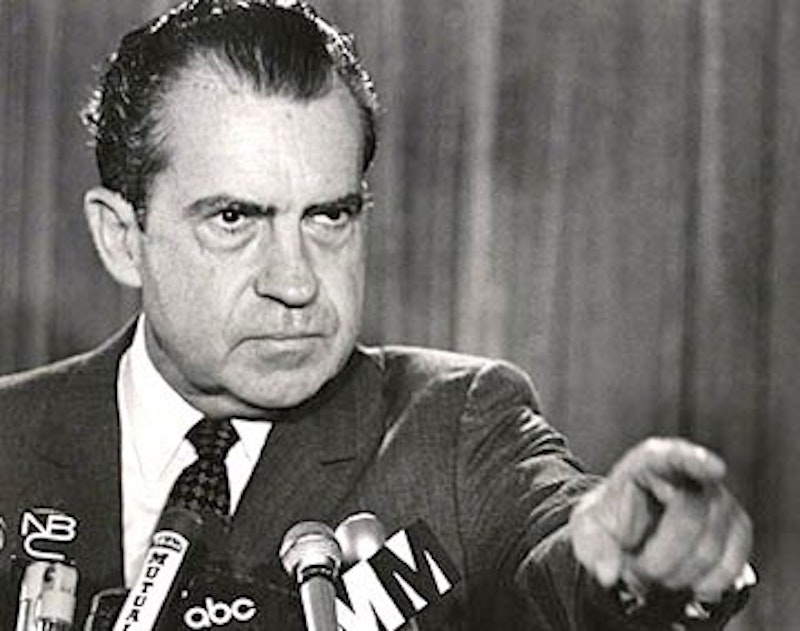

Years ago I read a pundit's account of a miracle call by Richard Nixon. Everyone wants to be a sharp guy who can see the angles in a political situation and know how it's going to play out. Nixon still has a reputation as the sharpest of the sharp guys, and after his death various columnists entered tributes to that effect. This one recalled a Nixon between political jobs, waiting out the mid-1960s. He had his eye on 1968 and another try at president, but a new sensation had come up on the horizon. New York City's handsome incoming mayor, John Lindsay, was a Republican who had taken the city, a Democratic stronghold, by beating the Democrats at being liberal. He was a beautiful, broad-shouldered piece of manhood and the press said he might go all the way, ride a political shift that knocked the Democrats out of Washington and installed a gang of chisel-chinned liberal Republicans in their place.

Nixon said no. Obviously, he said, what would happen was that the guy would become a Democrat. New York State already had a gorgeous, liberal Republican governor in Nelson Rockefeller. The governor and the mayor would chase the same headlines, and in the end the mayor would get squeezed out and drag his sorry hide to the other team. Which is exactly what happened, phase by phase, until four whole years of New York political history had gone by. Nixon saw it all that afternoon from his office on Wall Street, wondering when his cottage cheese and ketchup would get there and he could start lunch.

I can think of just two other political calls on the same level. One was by Pat Buchanan. The communists over in Russia had just put in a leader who wanted to shake things up and get the country going again. Buchanan said maybe he'd be the Louis XVI of the Soviet Union. It turned out this was so. Half a decade later Russia was falling in on the head of the dynamic new leader, who is now a dependent of the international high-mindedness circuit (think tanks and conferences, the UN, things of that sort). The Soviet Union collapsed like the French monarchy, and a right-wing pundit's bit of propaganda turned out to be, damnably, a correct and prescient reading of a giant and unfamiliar new situation. Everyone else has forgotten Buchanan's Louis XVI line, if they noticed in the first place. But I can't let it go. It just bothers me.

Buchanan did make an ass of himself, prediction-wise, when the Soviet cave-in finally took place. I saw the scene on television. Brow furrowed with challenge, he demanded that a nice professor from Princeton acknowledge that Boris Yeltsin (the lead rebel against Soviet authority) was a far greater figure in history's scale than poor Mikhail Gorbachev, this schmuck of a Soviet boss who had fumbled his way to the regime's end. The professor gawped. His face was knocked silly by the dilemma that sometimes overwhelms a good liberal: How do I make my brain small enough to answer this point?

The professor saw a world-historical situation toppling into place; Buchanan saw one man, Yeltsin, show the right kind of set and thereby outclass the other man, Gorbachev. Undeniably, Yeltsin had just climbed atop a tank and told the Soviet military to back off from the coup it was trying. He did this while Gorbachev sat in captivity, no longer president of the Soviet Union and instead just a pawn taken prisoner by his own soldiers, his string played out at last, the conferences and think tanks lying dismally ahead of him. But Buchanan had to bring the long run into it, history's judgment. He had to make a prediction, and it turns out that the birth of the new Russia is still known as Gorbachev's era. Well, sure. Gorbachev was the man who did history's heavy lifting, who dismantled one of the world's biggest, ugliest and most important dictatorships. Yeltsin became the man who inherited Russia and let it sink deeper into the crap while he drank himself stupid. An important role too, but secondary.

Buchanan should have stuck with that one happy season when Yeltsin was top gadfly of the late Soviet regime and nemesis of an easily discouraged Soviet military. But the damn pundit had to look ahead, had to guess at the triumphant unfolding of facts that would prove him right about everything. The facts did not unfold correctly, and the poor gaping professor was left with a better read on things. I don't think the professor quite got it out of his mouth, but put the read this way: Stuff like this is complicated, and history can bend itself into shapes that will really surprise you.

Note that being dead-on about Gorbachev's chances at success didn't help Buchanan when it came to making his big call about Yeltsin. He might well have been more on top of late Soviet developments, in their broad tendency, than the professor was, at least if the professor thought Gorbachev had a chance at making the Soviet system into something with a future. Yet Buchanan still flopped. This makes me think that the prediction impulse is less of a mental process and more a kind of mental short-circuit, a tic that has full override power over normal functioning.

Present the modern brain with a certain class of data and it must shuffle that data around until some reason for self-satisfaction has been constructed. For most white-collar joes this sort of data definitely includes the political headlines of the day. It's not enough to process this information and lay it by. The player must also show their superior understanding of the data by calling its long-term implications before anybody else. So the brain is convulsed into a repetitive activity that's of borderline usefulness except in keeping your self-image from slipping down the wall. The whole thing is a shuck, really.

I say this as someone who predicted the entire course of Ronald Reagan's second term. Here's how it happened. I was just out of college and Reagan was heading for reelection. My father's self-important acquaintance said that of course Roe v. Wade was a goner because Reagan would have four more years to appoint Supreme Court justices. The acquaintance had been talking a lot and I was very impatient with him. I said that, no, Reagan's reelection victory would be so big that his team would become dizzy with success. Then the team would overreach, get caught in a scandal, and find themselves minus the clout necessary to line up the Supreme Court they wanted, so Roe v. Wade would survive.

My father didn't care about my little discourse, and neither did his acquaintance. I expect they forgot the remarks the moment these had dropped from my mouth. But I was right. Through the second half of the 1980s, month by month, a run of newspaper headlines bore out my status as a successful caller of the curves up ahead in history's river. There was Reagan's 49-state win, the missiles sold to Iran, the money sent to the contras, Oliver North's testimony, the Tower Report and the fizzled attempt to put Robert Bork, right-wing judicial ideologue of note, on the Supreme Court, followed by a fizzled attempt with another would-be justice, followed by the White House saying the hell with it and compromising.

We had a chain of shambolic political extravaganzas that kept the news world barking for years. I had called the bones of it that evening, and I knew how it would play out: with Roe v. Wade still alive, as the decision is to this day. Nobody cares that I did this, and I can't even prove that it happened. In fact my Nixon-class miracle guess has never done me any practical good. I can't even bring it up in conversation: I'd look like a vainglorious chump. And for all I know, everyone else is in the same fix. We might all have our one moment when we hit it out of the political-prediction park, a moment that turns out to be our secret because there's no way too talk about it without being small. Whatever. I've got mine and I'm going to keep it the rest of my life. In August 1984 I was as smart as Richard Nixon. There has to be some reason I've read all these damn newspapers, and that might as well be it.