This very week, if memory serves, marks the 25th anniversary of the first time I sent an email, and the world has been getting creepier and creepier ever since.

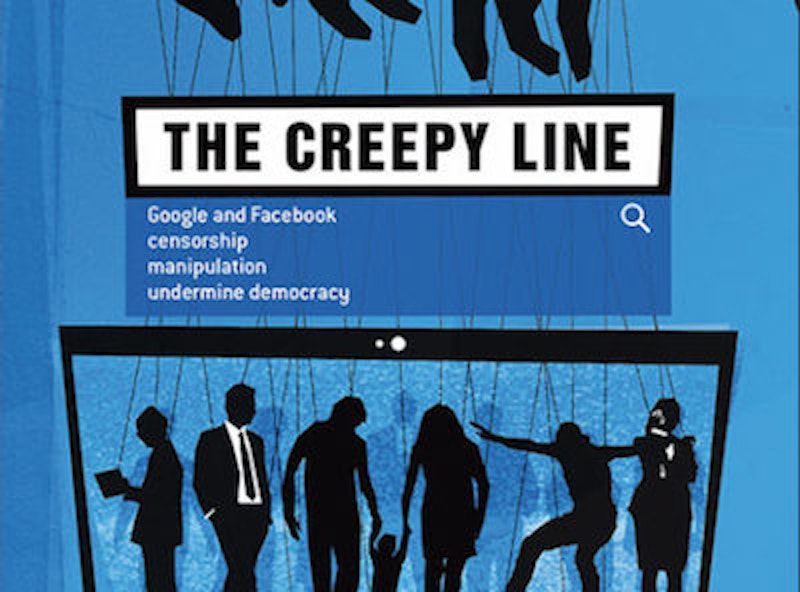

The unsettling new documentary The Creepy Line (from some of the same people who brought you the expose Clinton Cash), directed by M.A. Taylor, is a timely look at the way Google and other tech firms can already subtly skew the way you perceive the world—and skew elections in the process—without you even realizing it. (And recall that the human brain has serious problems with confirmation bias even without machines amplifying the effect.)

We can probably guess which direction tech people skew elections, too, judging by recently-revealed footage of a Google exec weeping as she recalled Clinton’s election loss (perhaps she was consoled a bit by the email another Google exec sent out the next day, bragging about how much the company had done to try turning out Latino voters in swing states).

As interviewees Robert Epstein and Jordan Peterson, both psychologists, explain in The Creepy Line, Google not only can nudge your search results to make you like a candidate or political position more, shifting a few million pivotal votes, but can bury search results for articles critical of Google. Epstein plausibly describes that happening to an article of his in USA Today. They can even cut off your ability to use Google itself if they don’t like what you say, as happened to Peterson—who despite what you may have heard, is barely a conservative, let alone a dangerous radical. He just takes a schoolmaster-like “get tough” approach to psych advice in his talks, rather than strive to sound modern-liberal, though he still sounds pretty modern-liberal by any reasonable standard.

I recommend the film highly but get a bit more cautious when Epstein hints (at least in a talk after the screening I saw) at his preferred solution to the problem. He doesn’t think any private company can be trusted to wield the kind of influence Google has, but that means he’s basically recommending search engine communism—or at least something like the EU’s crackdown on tech, but far from enshrining free speech, EU regs may soon yield fines as big as four percent of annual corporate revenue if tech platforms don’t remove offensive material within one hour of being warned by authorities. Dr. Epstein objects to this characterization and has been lauded by libertarians for recommending a voluntary system of private monitoring like the one he describes here.

I hope our hyper-politicized current culture hasn’t forgotten how bad political power is at fixing technical problems. Painful as it may be, we’re just going to have to create more and more tech resources until market competition puts the quasi-monopolies in check, I think.

Otherwise, you’re just taking power from Mark Zuckerberg and handing it to the likes of Diane Feinstein. No thanks. I’m available to mediate between tech and conservatives for a large fee if necessary. I’m still hoping the common ground, so to speak, can be markets instead of a government-run commons. But I admit it’s strange new territory and the old philosophies may not map onto it perfectly. (Google Maps doesn’t either.)

In any case, I’m grateful I lived through the 1980s, 90s, and 00s if we end up looking back at those decades as the short-lived peak of free speech in the world (they swore on the radio and sometimes had nudity on basic cable). I’m not despairing quite yet, but the examples of tech-censorship, or something close to it, do seem to multiply by the day. Just ask my fellow Creepy Line audience member Gerard Perry, permanently banned from Twitter, apparently mainly for pointing out jihadists using the site without half the censorship troubles conservatives run into.

To me, two of the most disturbing tech discoveries of recent times are the revelation that some word processing programs will intrude upon your private documents to tell you your language is offensive and the revelation that our phones are always listening and feeding keywords we say to all the major social media platforms. The algorithms are becoming so adept at shoveling you more of what you love that using a computer is starting to feel like some unsettling version of “lesser magic” in which you’re continually conjuring the things to which you allude in speech. It ain’t natural, and it’s intensifying.

Yet even now, some tech CEOs continue artfully denying the phone-audio-snooping routinely happens (with help from some servile, dismissive, “debunking” tech writers, at least until very recently). That sure seems to me like grounds for a class action suit by deceived customers, but then, I still believe in truth. And anti-fraud suits.

Just in the past week or so, though, we’ve also seen the pick-up artist Roosh get his books banned from Amazon, #WalkAway founder Brandon Straka banned from Facebook for linking to Alex Jones, and conservative J.P. Freire, strangely, temporarily banned from Twitter in the present for using the phrase “Die Hard” several years ago, a sign the algorithms really may not know what they’re doing. But in a reminder the problem is as much one of culture as of new tech, old-fashioned institution The Tonight Show, apparently amidst anguished tears from staffers, reluctantly uninvited Norm Macdonald from appearing because he sympathized too much in recent comments with ill-behaved Roseanne Barr and Louis C.K. after they suffered recent controversies.

Attempting to explain later, Macdonald also managed to insult people with Down Syndrome, and frankly I hope he keeps digging a deeper and more disquieting hole, which is sort of his shtick, after all. I mean, they probably can’t actually put him in jail, right? Not yet, anyway. Make trouble. (Sophia Benoit, for her part, tweeted the world an angry reminder that Macdonald is a dumb Christian who doesn’t even believe in DNA. That doesn’t make her funnier than he is, though.)

Note that all this isn’t just a problem for conservatives: The site ThinkProgress understandably complains about a system wherein Weekly Standard, a right-wing (and hawkish) magazine, is allowed by Facebook to weigh in on whether pieces are misleading enough to warrant reduced visibility—leading to Facebook zapping one of ThinkProgress’s anti-Kavanaugh pieces into obscurity.

How about just genuinely letting users/readers decide for themselves, maybe even give them elaborate filter controls they can use to be as open or as narrow-minded as they like? We let the masses buy their own books, you know. I shudder to think how frightened our culture would be of printing presses if the Guttenberg revolution happened today instead of six centuries ago.

Of course, printing presses do bring some of the same problems as Facebook et al: To this day, you have to take care producing bawdy comic books lest the often Christian-owned printing companies reject your order at the last minute. It can affect content even at the big comics publishers. But at least that process is less opaque and deceptive than the weird, subliminal things the tech giants do.

It's not that we didn't see this tech problem coming based on past forms of censorship. It’s just that—let’s be honest—we figured hip tech people would be more tolerant and cool about it all. Live and learn.

—Todd Seavey is the author of Libertarianism for Beginners and is on Twitter at @ToddSeavey.