On March 13, I received a personal email from Atlantic editor Jeffrey Goldberg. Or at least it appeared to be personal, given that I’m an anarchist. Let the round-up begin! was the spirit. Touting a story called "the new anarchists" by executive editor Adrienne LaFrance, Goldberg says she pitched him on the question of how we can call a halt to our societal breakdown.

To find the answer, she looked overseas, and across history, and found lessons for our nation that are both deeply complicated and crucially important. Adrienne’s latest cover story, “The New Anarchy,” is the result of that effort. It also represents a larger interest of The Atlantic’s at this moment.

I’ve asked our journalists to focus on political extremism with singular intensity, particularly as we approach the 2024 presidential election, and as conditions for further political violence ripen. Our commitment to this coverage area is nonnegotiable because extremism threatens the American experiment, and The Atlantic was founded to advance the American idea and to help bring about a more perfect union.

It's true that "goldberg" writes bottingly ("deeply complicated," "crucially important," "the American experiment," "a more perfect union”: these are the words of an Obama app), which is one contrast between himself and extremists like me, who tend to formulate sharply. Goldberg's bottery is a comforting mumble, extremely unextreme.

But I do hear that Goldberg and company have dedicated themselves to saving the country. Richly-confirmed rumor has it that the Atlantic will be opening a sprawling system of internment facilities for extremists such as myself, to be administered by the Pew Foundation. Plus they'll be urging more content moderation, though I appreciate that LaFrance is no longer blaming Faceboook and leaving it at that, because that shit was ridiculous.

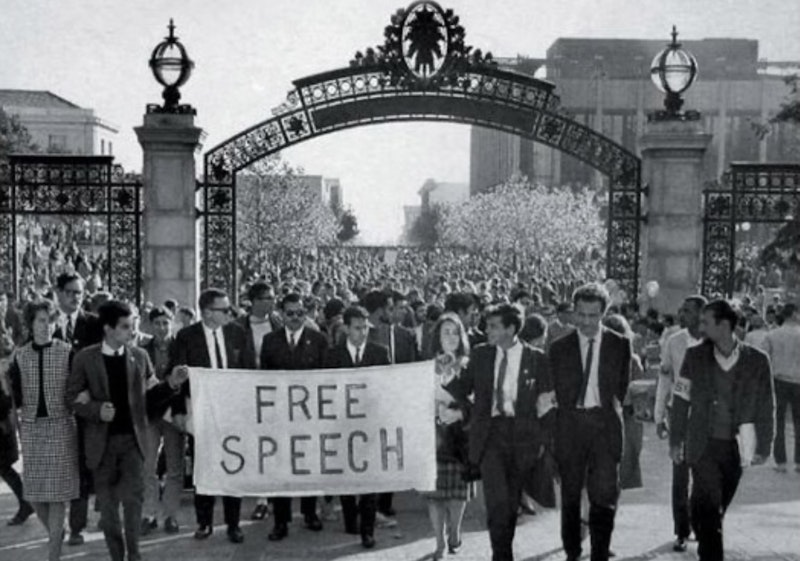

LaFrance's approach amazes me in its straightforward honesty, which leaks out just before she can formulate all the disclaimers. She is—really, sincerely—suggesting a new wave of obviously unconstitutional and also obviously authoritarian speech repression, and hardly bothering to pretend otherwise.

I didn't think she really meant “anarchists,” but she really does. LaFrance rehearses the history of anarchist violence around the turn of the 20th century, when anti-statists committed a series of assassinations, including President William McKinley, and other acts of violence. Now, I’m an anarchist in that I do not think there is any plausible justification for government. But like a lot of other anarchists, I’m not an advocate of violence, in fact I’m a Quaker and a pacifist. And I think, as did many anarchists at the time, that the terrorism was completely counter-productive and was one factor that led to the end of anarchism as a viable political movement.

The reasons that anarchists more or less stopped committing acts of terrorist violence are complicated. "Propaganda by the deed" turned out to be completely ineffective. Far from leading people to rise up, it caused disgust and repudiation, as well it should have. The fundamental factor, though, was that the 20th century just completely went the other way: it was the golden era of unprecedented, extreme state power, as expressed everywhere from the Soviet Union to New Deal USA to Imperial Japan to fascist Italy and Germany. The "direction of history," that is, made the idea that the state could or was about to disappear seem completely implausible.

These aren’t the factors that LaFrance picks out. She attributes the decline of anarchism straightforwardly to government repression. The US government explicitly prohibited anarchists from immigrating here, one of the only times a particular ideology has explicitly been singled out as disqualifying. The Palmer Raids resulted in hundreds of deportations, including of the great anarchist leader and writer Emma Goldman (who then had to go confront Lenin with his own statism).

A concerted nationwide hunt for anarchists began. This work, which culminated in what came to be known as the Palmer Raids, entailed direct violations of the Constitution. In late 1919 and early 1920, a series of raids—carried out in more than 30 American cities—led to the warrantless arrests of 10,000 suspected radicals, mostly Italian and Jewish immigrants. Attorney General Palmer’s dragnet ensnared many innocent people and has become a symbol of the damage that overzealous law enforcement can cause. Hundreds of people were ultimately deported. Some had fallen afoul of a harsh new federal immigration law that broadly targeted anarchists.

The violence did not stop immediately after the Palmer Raids. Nevertheless, sweeping action by law enforcement helped put an end to a generation of anarchist attacks. That is the most important lesson from the anarchist period: Holding perpetrators accountable is crucial.

Now, regarding the Palmer raids and waves of warrantless arrests and ideological deportations as fundamentally good and effective: not many historians have looked at it that way. Really read that first bit again and see whether you think that’s okay. As you do, ponder what people like Goldberg and LaFrance actually mean by phrases like "the American experiment." But it's not hard to see what sort of person endorses this approach. Persons such as Adrienne LaFrance and Jeffrey Goldberg, in short. I'm just hoping to fly under their radar, so I hope this article in Splice Today doesn't trigger the Google alert that they have on their names.

LaFrance does immediately apologize for the disgusting unconstitutional indiscriminate repression of laws that targeted specific ideologies (as some do today, for example on critical race theory) and for the Palmer raids and concomitant political detentions and deportations. But these are meaningless disclaimers, and she’s urging new waves of repression aimed at people she opposes: QAnon advocates (if there still are any) and Trump supporters. In this piece and many others, LaFrance is directly advocating an ideological crackdown: a new series of anti-expression laws, new waves of political deportations, new Comstock laws to suppress social media, and so on.

The analogy of today’s QAnon or Trump or Brexit wave to 1900 anarchism is ridiculously strained. The right and the left as we know them now or as polarized all over, have nothing to do with anarchism whatsoever: it's statists against statists trying to see who can suppress whom. “Anarchist” in this context is nothing but an insult; it has no meaning. With just the same sophistication and precision, Goldberg and LaFrance could refer to their opponents as "fuckwads," say, and propose legislation to outlaw fuckwaddery.

But the email made me melancholy, and I have a question for Jeffrey Goldberg: Is there really no way out from under the Atlantic for an extremist like me? Is this really non-negotiable? Maybe I could write for you cheap in words reprocessed from Obama? No wait, you have, or are, bots. Maybe if I renew my subscription? But I thought you said, "cancel at any time"!

If I pretend to agree with you, is that good enough? My pacifism constrains me not to endorse violent resistance, into which LaFrance seems so intent on cornering people.

—Follow Crispin Sartwell on Twitter: @CrispinSartwell