"Donald Trump and I tell very different stories of America," Barack Obama has pointed out many times, and one of his most questionable contributions to political discourse has been to intensify the idea of politics as fundamentally narrative construction, a sort of novel or (looking at it hopefully) a variety of creative non-fiction. The 2008 campaign was the acme of postmodern politics, in which the countenance and words of Obama got “framed” in a story of American history, as something of a climax. With the Obama campaign's billion-dollar encouragement, people re-read history retroactively as what would lead us to him and that moment of redemption.

I don't mean to credit/blame Obama exclusively for this. His approach hooked on to a mood visible everywhere from the higher reaches of academia to the latest car commercial: the grand idea that our identities, individual and collective, consist in the stories we tell. The primary or even the only practical application of this is that stories can be employed to manipulate people's behavior as voters and as consumers. Voting and consumption can’t be distinguished in campaigns that spend billions of dollars on marketing.

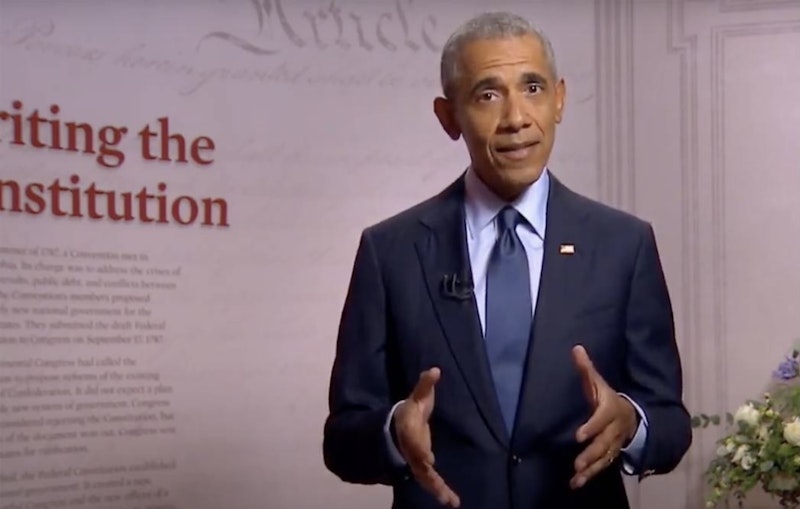

"The truth is," Obama continued, "in a lot of ways, the job of a writer and the job of a politician overlap. Both are trying to tell a story that connects with folks. I mean, Donald Trump and I ran on very different stories about what America is all about, but you can’t say either of us didn’t tell a story."

Obama’s everywhere these days; I wonder how many interviews he's done in the last few days. He's on a book tour, of course, for his memoir A Promised Land. That title encapsulates the scale of the Obama-style narrative: it's biblical. If this is the promised land, then we are the chosen people, boys and girls, placed on this earth to redeem it. Obama didn't invent this narrative; he absorbed it from sources like King.

It’s also remarkably similar in its outline to the “America, here to save the world” vision of neo-conservatism, for example—the narrative provided by Richard Perle or Dick Cheney—though the Obama style connects "realizing America's promise" or "living out the true meaning of our creed" primarily to racial or economic justice rather than to our alleged destiny to bring freedom to a benighted world.

I’d like to raise some questions about narrative politics at this grandiose scope. I think Obama, and broad swathes of the American public that found him inspiring, took it for granted that if many people accept a sweeping narrative where everything leads to a good outcome, that makes a good outcome more likely. But eight years or so of installing the narrative from the world's most powerful perch, speaking it all-day every-day into the world's biggest megaphone, only got you to Trump. A narrative construction, even the most perfect or comprehensive or seamless or seemingly plausible, is easy to refute. You just tell a different story.

Is America living out the true meaning of its creed as the place where the arc of moral universe bends toward justice? Or did it lose the true meaning of its creed or the real meaning of American identity somewhere along the way, our coming redemption consisting in its recovery? On such questions, any American fact at all—any of the facts in their trillions —is relevant, and all the American facts aren’t dispositive. When you simplify and drift free of reality to this extent, no empirical data bears at all, or any empirical datum of any sort is absorbable into the narrative. You could narrate history in indefinitely many ways, all of them equally connected to and equally detached from all the particular facts. What would you expect to happen next year if the Obama narrative were true that couldn’t happen if the Trump narrative were true, and vice versa? What actual evidence could possibly count either way? If I could, I'd like to coax you gently back to the world.

In the narrative and counter-narrative, "America" ended up split between two gigantic, hyper-simplistic stories of itself, relentlessly marketed and endlessly repeated.

The picture of politics as creative writing (with attached publicity machine) that Obama endorses sits in remarkable tension with other beliefs that he and his ilk profess. The way I'd put it is that Obama holds two entirely incompatible theories of truth simultaneously. The one makes truth a narrative construction that everyone accepts together. The other relentlessly claims to be representing the hard objective facts. "Well, the truth is the truth," Obama tells The Guardian as he devotes himself once again to countering disinformation, conspiracy theories, "alternative facts," and science denialism. If there's one thing that climate change or the anti-vaxx movement has shown us, it's that you're entitled to your own opinions, but not your own facts. And so on.

I'm tempted to tell Obama that, in that case, he ought to abandon the idea of politics as story-telling, or else endorse it consistently and narrate us out of climate change. Maybe if we all believe together that the earth must cool for we are the chosen people or something, everything will go great.

In other words, this idea of the world as a more or less fictional construction sits extremely poorly, first, with a bunch of other ideas you want to sell, and second, with facts we all need to face. If the Obama-to-Trump transition showed anything, it was that we can’t narrate ourselves out of racism, for example, any more than out of climate change, particularly when the narratives arrive at this bloated level, encompassing all possible facts and explaining none of them.

I don't think that governing is primarily about story-telling, even if selling it is. I'd like to entertain the hypothesis that it only matters insofar as it engages concrete, specific facts. In a contest for power, you can have all the narratives. Just leave me the weaponry and the Fed, and I'll be good.

—Follow Crispin Sartwell on Twitter: @CrispinSartwell