The greatest filibuster on film is the work of a Republican from Indiana, Pennsylvania. The work is in keeping with the image of an everyman, of a scoutmaster too benighted to know better and of a senator too benign to better the Senate. But the man whose first name is the last name of the author of America and whose surname is the most common last name in America, this man, Senator Jefferson Smith, doesn’t exist. The actor who plays him endures on film, just as the medals of his valor—including his three Air Medals, two Distinguished Flying Crosses, and Croix de Guerre—live on after his death, for the memory of Jimmy Stewart is the literal translation of Princeton in the nation’s service.

The life of Jimmy Stewart isn’t, however, the way John Fetterman lives his own life.

Any similarity in sound is due to how a comic does Stewart “doing” Katherine Hepburn, or Hepburn trying to start her car, the two peaking in a wash of onomatopoeia.

If Fetterman doesn’t sound this coherent, and I make no pretense to diagnosing anything more than his political condition, he’s unfit to serve in spite of what he believes.

If he takes his obligation freely, without any mental reservation or purpose of evasion, he doesn’t know what a senator has a moral obligation to do: communicate.

If he wins election to the Senate, after defying death with medical assistance in May and nearly dying while debating a doctor in October, what is the likelihood he’ll convalesce by writing or rouse an audience by speaking?

Picture a senator in the bedroom of his childhood home, where he dictates memos and revises sections of his manuscript.

Picture the senator as the representation of the ninth and newest chapter in a story about the triumph of principle over politics, of a man whose appearance evokes that which he invokes: vigor.

Now picture the impossibility of John Fetterman as John F. Kennedy.

Or picture a politician speaking nine months before the publication of Profiles in Courage and four months prior to the second anniversary of his own stroke.

Picture him frail, but not faltering, as he speaks for the last time about a time he’ll not live to see and a world he hopes the living will entrust for endless, perpetual posterity.

Picture the audience before him, consisting of members of every party and of almost every point of view, as he speaks about the power of science and the responsibility to prevent attempts to pervert science; as he speaks of a past too new to be past and a crime too incomprehensible to have a name; as he speaks about a paradox, but not in despair, saying, “The worse things get, the better.”

Picture this man of patience and courage saying, “Never flinch, never weary, never despair.”

Now picture John Fetterman as Winston Churchill.

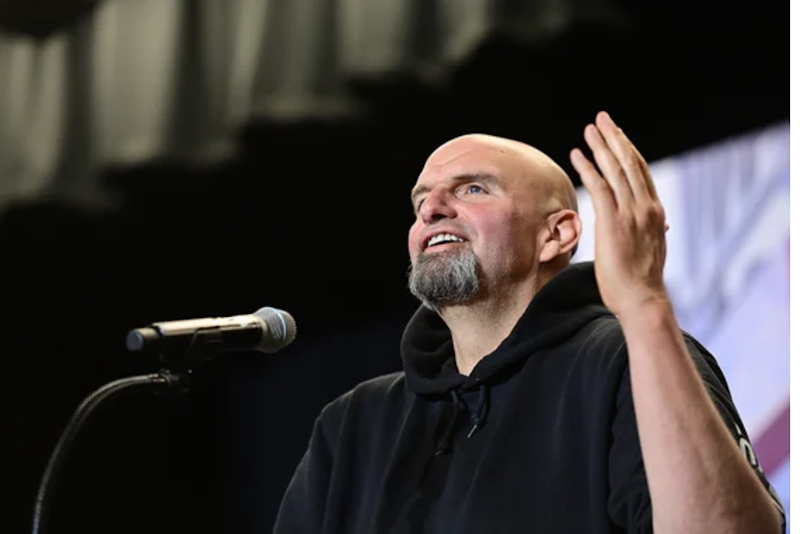

Picturing Fetterman as a senator is less difficult than picturing him saying or doing anything memorable.

To see him as he is, in the state he’s in, makes it unfortunate to believe John Fetterman should be in the United States Senate.