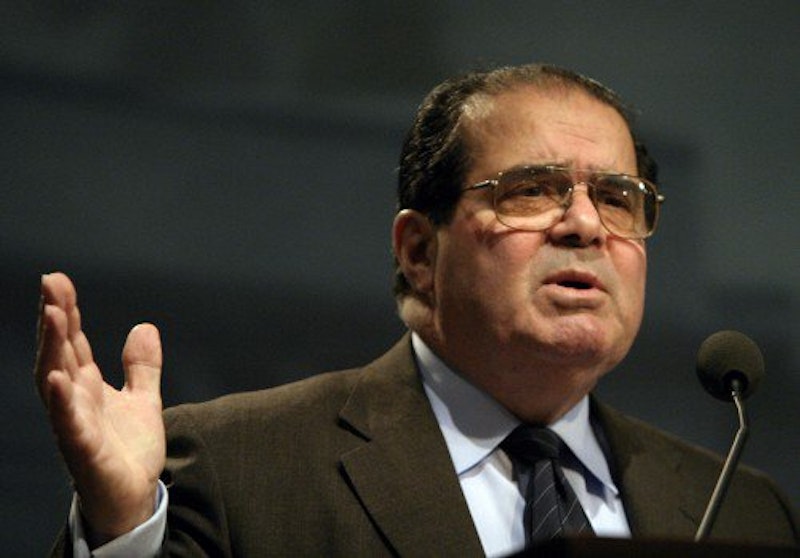

The free-market movement—if I can still use that broad term in a divided era—has tended to like the late Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, though not without reservations. He deeply respected the Constitution and the importance of having predictable, knowable, shared legal rules in order for society to function—without politicians or judges dangerously making things up on the fly—but he was also prone to defer to the legislature, and to the government generally, far more than a libertarian might like.

The basic libertarian understanding of the Constitution—which we’d argue we more or less share with the Founders—is that when in doubt, the government should not act. It has a very short list of enumerated powers—and nothing more. Scalia’s view was more that the government should be given the benefit of the doubt unless it had clearly strayed beyond the powers it was supposed to have. Give it leeway until it definitely crosses the line, you might say.

In this, he was not so unlike the majoritarianism-inclined Judge Robert Bork, who was nominated to the Supreme Court one year after Scalia but not confirmed (and who passed away just over three years ago). I’m of course glossing over countless legal-philosophy nuances and may even end up chastised by lawyers because of it, but for purposes of a short column, this will have to do.

Whether a law code leans libertarian, conservative, or social democratic, though, there are libertarians, conservatives, and liberals who all agree that predictable rules—the rule of law—is a much better, safer state of affairs than the government’s powers expanding and contracting on a whim. At his best, Scalia was trying to avoid that sort of randomized legal chaos, with all the potential for tyranny it brings (in the guise of expediency or just “seeming like a good idea at the time”).

I got to see Scalia speak live once when I was in college. The most telling moment may have been when, grilled by a leftist student in the audience who happened to be a semiotics buff, Scalia said, “If you don’t call me a strict constructionist, I won’t call you a deconstructionist.”

That’s the fear, after all. Descent into postmodernism and interpreting the Constitution however you like may spawn things far stranger, rooted in nothing more than fleeting bad ideas among the public, than sticking to a known document—which, Scalia liked to remind people, can still be amended if we don’t like it, but not just reinterpreted willy-nilly. You wouldn’t like companies “reimagining” their contracts with you instead of clearly and forthrightly negotiating to revise the text.

As a relatively politically neutral friend of mine (more interested in math and science than law) once put it, what we want most of the time from any set of rules or indeed any person purporting to act according to some ethical or legal code is predictability. If I’m dealing with socialists, say, at least let me know that in advance, so I can attempt to influence the next Party Congress or whatever the decision-making process is, but don’t just pull the rug out from under me—especially not literally, if I’d been led to believe I owned the rug.

Libertarians who want strong property rights, conservatives who look to tradition and precedent, and liberals who value due process can all appreciate that point in their different ways—and I hope whoever ultimately replaces Scalia on the Supreme Court will as well.

—Todd Seavey can be found on Twitter, Blogger, and Facebook, daily on Splice Today, and soon on bookshelves with the volume Libertarianism for Beginners.