R. Sargent Shriver, who died last week at 95, was memorialized for many things but not a single obituary recalled him as a semi-serious contender for governor of Maryland in 1970 and a potential challenger to Gov. Marvin Mandel who, for the first time, would face the voters that year. Following is a personal account of how Shriver was squeezed out of the race. It is adapted from an unpublished manuscript.

* * *

The rules of politics are the rules of the marketplace. Much of the second half of 1969 was devoted to preparing for Mandel’s 1970 campaign for election by the voters to his first full term as governor. The hiring of professionals, the assembling of a campaign staff to supplement the State House staff, issues research, strategy planning, the next legislative program, locating a headquarters—all of the fine details of organizing an effective campaign that had to be ready not only as a show of strength and support, but also as a matter of political efficiency. The governor’s desk is where programs and politics converge and become policy.

One troublesome note for Mandel and his political team (which, for practical purposes, was virtually the same as his State House staff) was the persistent rumor that R. Sargent Shriver, ambassador to France and the high-visibility Kennedy in-law who had directed the Peace Corps, was considering returning to Maryland to run for governor. In a heavily Catholic state such as Maryland, Shriver could be a formidable candidate. Not only was Shriver a descendent of one of Maryland’s oldest families, but the handsome Yale-educated lawyer carried with him the glamour of the Kennedy association as well as the purchasing power of the Kennedy millions. Shriver’s ancestral home in the Carroll County seat of Westminster is a state-supported museum as well as an historic landmark. His own home in Maryland was located on an estate owned by the Mandel-appointed chairman of the Maryland Racing Commission, Newton Brewer.

Shriver was being courted for the gubernatorial challenge by two political operatives from Prince George’s County—Peter F. O’Malley and R. Spencer Oliver. O’Malley was a young, shrewd and relentless political taskmaster and organizer who had assembled the most efficient local political machine in Maryland. So effective was his organization that it captured every elective office in Prince George’s County at the time. O’Malley’s efforts to recruit Shriver were viewed as a shakedown of Mandel.

Oliver was a long-time Shriver friend and O’Malley’s emissary to Paris. Oliver would later achieve national notoriety for his phone being tapped during the Watergate break-in of the Democratic National Committee offices. And Oliver’s father, coincidentally, was a State House lobbyist for S&H Green Stamps, no stranger to Mandel. The senior Oliver privately called Mandel and pleaded with him not to inflict punishment on him for the sins of his son.

Early polls taken by Mandel showed that the Governor’s recognition factor was high and was viewed favorably by the voters. But the surveys also revealed that Shriver also had a high standing among Marylanders—especially among Maryland’s half million Catholics. There was no cause for alarm but there was reason for concern.

Mandel was a master of tying up loose ends. Among the first steps Mandel and his political advisers took was to assemble the very first and best team of political and media consultants in the nation at the time. The first hire was Joseph Napolitan, the internationally renowned political consultant and pollster. Napolitan had worked as consultant and pollster—along with Lawrence O’Brien—in the 1960 campaign of John F. Kennedy. And later, he had worked in the presidential campaigns of Lyndon Johnson and Hubert Humphrey. Napolitan still had close ties to many of the Kennedy family members and served occasionally as an adviser to Sen. Edward Kennedy, of Massachusetts, Shriver’s brother in-law.

Through Napolitan, the campaign media team was rounded out with Robert Squier, the television producer, and Tony Schwartz, regarded in political circles as the best producer of radio (and occasional TV) political commercials in the country, his most famous being the so-called “Daisy” commercial in the 1964 Johnson-Goldwater election. Locally, the media team was supplemented by adding the Rosenbush Advertising agency to handle local time-buying and other campaign paraphernalia. I would coordinate the media team and media production as well as the issues campaign from inside the State House, straddling both the campaign and the governorship. But that was before Watergate and the new layers of campaign reforms.

Next, Mandel concentrated on Shriver the persona and whether he was actually eligible to run for governor. Maryland law requires that its governors be residents and registered voters for five years prior to assuming the office. Among the factors that determine residency is where a person pays taxes. Mandel obtained an attorney general’s opinion which stated that a candidate for governor must have paid taxes in Maryland for the past five years in order to be considered a resident.

Shriver had lived in Chicago where he managed the Merchandise Mart, a Kennedy family holding, and served on the city’s school board. Mandel’s researchers uncovered the fact that Shriver had indeed paid taxes in Chicago but none in Maryland. Shriver later attempted to pay back taxes in Maryland, but Mandel was prepared with a second ruling stating that this was a tacit admission that he did not consider himself a resident of Maryland.

But the crucial nail was a decision by Shriver himself. Shriver was little-known in Maryland with no power base whatsoever. Napolitan recounts in his 1972 book, The Election Game, that “Few political figures in Maryland leaned his way, and, for some reason inexplicable to me, Shriver appeared determined to court their favor instead of plunging headlong into the race and defiantly crying that he would let the people decide.”

Napolitan, as consultant and pollster to Mandel, believed that “We could take Shriver if he decided to run but that it would cost a lot more money than Mandel had planned to spend in his campaign to do so.”

Thus began the systematic leaking of poll numbers showing that Mandel was well liked and virtually unbeatable. Political leaders across the state lined up solidly behind Mandel. And Mandel, in turn, counseled them to be courteous and polite to Shriver while declining to support him. “Wherever Shriver turned, he found his way blocked by politicians who promised all kinds of support if he would run for congressman or senator or something else—but not for governor,” Napolitan wrote.

Another component of the strategy to eliminate Shriver was an early burst of media aimed not at the voters but at a single person—Shriver. “The whole thrust of the [media] campaign was to convince Shriver that Mandel had popular as well as political support,” Napolitan wrote.

“The spots, created by Bob Squier on television and Tony Schwartz on radio, emphasized the endorsement of ordinary voters around the state who spoke in glowing terms about Mandel,” Napolitan wrote. “These were real, not faked, and did reflect Mandel’s support.”

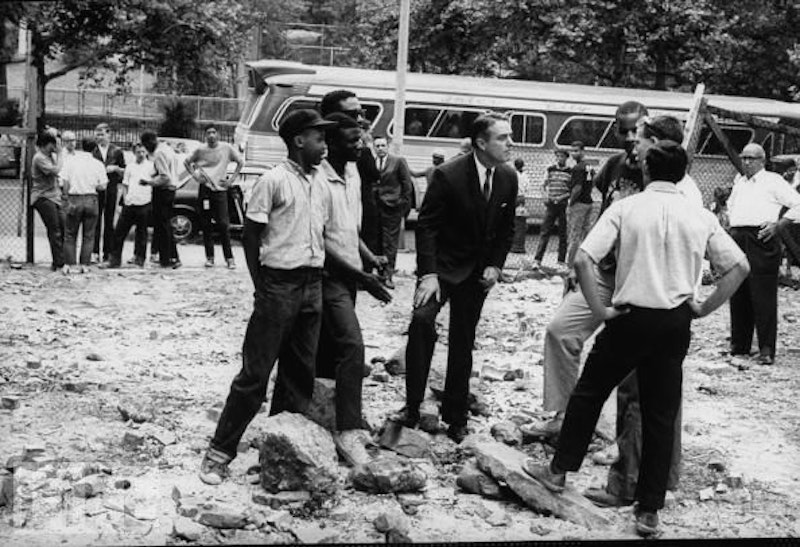

Sargent Shriver came home from Paris in March, 1970. He announced that he planned to get in his station wagon and tour the state to meet its political leaders. Mandel passed the word to his allies in the counties and Baltimore City to be polite and cordial to Shriver, to listen and smile before gently deflating his candidacy.

The day after Mandel’s return from a post-legislative session Caribbean vacation, a meeting was scheduled in Mandel’s office with Shriver—at Shriver’s request. The meeting was announced to the press and made public, as public as possible, and it attracted a room full of reporters from the national press as well as those who regularly covered Maryland politics.

Shriver, the mannerly aristocrat, made the serious but unavoidable mistake of asking to meet with Mandel, the cunning Machiavellian politician, on the governor’s turf. Mandel, as governor, controlled not only the stagecraft but the flow and the direction of the conversation as well.

The two stayed behind closed doors for more than an hour for what Shriver later described as “a very cordial discussion.” If Shriver knew that he had been used, neither his face nor his remarks belied it. Mandel had deliberately kept Shriver in discussion that long to generate talk in political circles and to provoke speculation among reporters that Shriver was undecided about running and was considering making up his mind. What really took place, Mandel said after the private meeting, was Mandel giving Shriver an inconsequential dose of small talk about Maryland history and government. It was Mandel’s way of saying and showing that he knew more about Maryland than Shriver did, and therefore was more qualified to be governor. My own recollection through the fog of 40 years is that Mandel shared with Shriver the results of the poll showing that he would be difficult, if not impossible, to defeat in the primary election. But there’s only one person alive who can confirm that.

Shriver commissioned a poll which showed that it would be virtually impossible for him to defeat Mandel. The Mandel camp leaked the results of a poll which showed that it would be virtually impossible for Shriver to defeat Mandel.

Within a month, Shriver declared himself a non-candidate, explaining that his tour of Maryland disclosed amazing and unexpected unanimity of support for Mandel. He had been misled, he said, by reports of Mandel’s vulnerability.

“I deliberately kept him that long to start talk,” Mandel chuckled after the hour-long meeting. Unknown to Shriver, his candidacy actually ended on the day that he met with Mandel.

“Mandel’s fifty thousand dollar investment in an early media campaign probably saved him a quarter of a million or more that he would have had to spend if Shriver had decided to run, and also got him some favorable early statewide exposure,” Napolitan wrote.

There were a couple of other mischief-makers who had their hands out: Hyman A. Pressman, Baltimore’s comptroller and self-styled gadfly, threatened to run for governor unless Mandel appointed Pressman’s good friend, Harry Kauffman, to head the State Lottery once it was established by referendum on the ballot with Mandel; and George P. Mahoney, perennial candidate, who was persuaded to run for the U.S. Senate instead with the promise of a high-visibility state appointment and other considerations. Kauffman did not get the Lottery job. It eventually went to Mahoney instead.

The way was now cleared for a worry-free primary election in September and a general election showdown against Agnew’s hand-picked candidate, his former secretary of state and now his Washington chief of staff, C. Stanley Blair.

Frank A. DeFilippo was press secretary and a speechwriter for Gov. Marvin Mandel.