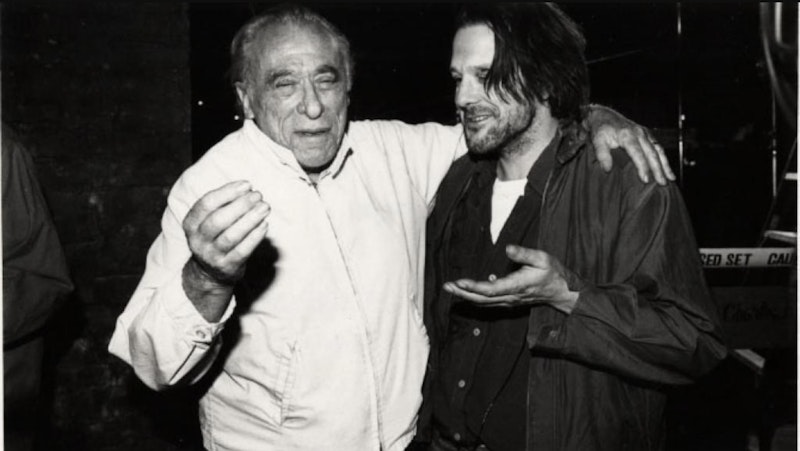

I was exchanging messages on Twitter with fellow Splice Today writer, Joshua France. He sent me a clip from Barfly, the 1987 film starring Mickey Rourke and Faye Dunaway. It’s a semi-autobiographical movie about the poet, novelist and occasional screenwriter Charles Bukowski. Rourke is doing an over-the-top impression of Bukowski, buying everyone drinks in a bar and toasting them with the words, “To all my friends!”

Bukowski’s very important in my life. I read his first novel, Post Office, in the early-1990s and was immediately struck by it. The writing style is very strong: vivid, simple, bold and direct, but with a poetic edge. It’s the poetry of everyday life, the poetry of the streets. There’s a touch of Hemingway, and a dash of Dashiell Hammett. It’s about the ordinary life of a United States Post Office worker, first as a mail carrier, and then as a clerk. It’s obvious that it’s autobiographical. There’s an urgency about it. It was only later that I discovered it had taken him less than a month to write. When asked by his publisher how he had managed to complete it so quickly, he said “Fear.”

Later I read some of his other novels. Factotum, his second, is so forgettable that I can’t even tell you what it was about, while Women, his third, is ugly and misogynistic. There’s a misogynistic element in much of his writing which is partly forgivable as he’s reflecting the speech and attitudes of working-class America, which is where the writing comes from. In Women, however, it’s relentless, page after page after page.

I also tried some of his short stories and his poetry. Both read like an extension of the novels. The same tone and voice. The same directness of expression. The stories are often narrated by Henry Chinaski, Bukowski's alter ego in the novels, and the poems might as well be. They’re like linear stories: snippets of events from his life, but laid out vertically like a poem, with a few words on each line. It was the poetry that made his name. He was a ceaseless contributor to small poetry magazines from the mid-1950s to the end of the 60s, while retaining his job as a Post Office clerk. For this feat alone we should celebrate the life and work of Bukowski: writing and writing and writing so prolifically, while maintaining a fulltime job, and still finding time to go to the racetrack and be a drunk.

But no matter what I read, none of it struck me in quite the same way that Post Office had.

My first thought on reading it was “I could do that.” I could write about my own life in the way that Bukowski was doing. I lived on a council estate at the time. This is the British equivalent of American projects: public housing for the poor. The one I lived on was on the outskirts of my home town of Whitstable. There were stories everywhere and I began writing them down. I was directly inspired by Bukowski. Eventually I sent a couple of my stories to the Guardian, where they were accepted. They came out in the form of a column called Housing Benefit Hill, which ran from 1993 to 1996. You can read some of my Housing Benefit Hill stories here.

That was followed by another column, CJ Stone’s Britain, which ran until 1998. I also wrote for the Big Issue, the Independent, Mixmag and a variety of other newspapers and magazines in this time, but after the Guardian dropped me I found it more difficult to get published. Eventually, after several years of struggle, two failed books and a long bout of depression, I decided that enough was enough, and I needed to get a proper job. I ended up working for the Royal Mail, as a delivery officer: a mail carrier in the US Post Office jargon. Just like Bukowski. This was in 2005. I worked there until 2018, when I retired.

I’m Bukowski in reverse. He was a postal worker who became a writer. I was a writer who became a postal worker. Not that I stopped writing. I had a column in Prediction magazine, and then one in Kindred Spirit. Eventually I started writing about life inside the Royal Mail, under the pseudonym Roy Mayall. Some of the stories appeared in the Guardian. You can read them here. There was also a book, Dear Granny Smith, which was Book of the Week on BBC Radio 4: read out in five parts at 9.45 every morning over the week beginning December 14, 2009. You can hear the complete set of Dear Granny Smith stories, read by Philip Jackson, here.

It was my most successful book, getting to number eight in the Amazon chart. It owes a lot to Bukowski, an attempt to write as simply and as clearly as I could what life as a postal worker was like. However, unlike most of Bukowski’s work, Dear Granny Smith includes a fictional element. It’s written in the first person, as Roy Mayall, but it’s not my life story. It’s the story of one of my colleagues in the office, Sid, as told to me over a couple of beers one afternoon in the Whitstable Labour Club.

After the exchange with Joshua France I decided that I needed to read Post Office again. On second reading, it’s not quite as good as I remember. It’s very sloppy in places, and the misogyny grates, but the writing’s still vivid and alive. I’d advise anyone planning a career in writing to read Bukowski. His style is a model of directness and simplicity. The opening line “It began as a mistake” is as good an opening to a novel as you’ll ever read.

I’m also reading Ham on Rye. It’s about Bukowski’s childhood. It’s much better than any of the other novels, less burdened with the writer’s characteristic cynicism. It’s written with the simplicity of a child, and it’s very moving and often disturbing. It reminds me a little of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man by James Joyce. The opening chapter of that book is also written from the perspective of a child and has the same directness and simplicity. Bukowski had a difficult childhood, with a violent father and a passive mother. He suffered from an extreme form of acne in his teenage years, acne conglobata, which may have been the result of the terrible beatings he suffered at the hands of his father as a small child. He was severely disfigured by facial scars. You begin to see where his personality comes from and it gives you a good insight into what made him a writer. Reading at first, and then writing, became a bulwark, a defense, against a world that had seemingly set him apart.

The act of writing is a way of coping with the world. By putting words on paper you’re distancing yourself from what you’re describing. You’re creating a fiction, even if the story is based upon real-world events. Bukowski’s alter ego, Chinaski, despite having lived the same life as his creator, is a fictional character. He’s a classic anti-hero, like one of those hard-boiled private eyes from a pre-war detective novel, a down and out Philip Marlowe. He allows Bukowski to relive these traumatic events in a way that will release him from their spell. Despite the writing’s discomfort, the occasional ugliness, Ham on Rye is really a work of redemption. It encourages us to observe the trauma in our own lives with the same unflinching honesty that Bukowski conjures, transforming pain into art. It’s undoubtedly Charles Bukowski’s greatest work.