There are 31 Republican governors in America, 26 states where the GOP shares control of State Houses, 246 Republican members of the House of Representatives and 54 GOP U.S. Senators, a numerical majority everywhere but the White House. If Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan (R) wants to fix legislative redistricting, as he claims, he should take it up with his Republican cohort that has gerrymandered American into a paralytic nation.

Instead, he presents the problem to the Democratic Maryland General Assembly in a more than two-one Democratic state as if the Congressional districts that resemble runaway ink blots are a lopsided problem. His nomenclators missed their big chance. Hogan could’ve made a splash at last week’s winter meeting of the National Governors’ Association, his first, by challenging his Republican peers to join a national effort to realign the states into a symbiotic but functional confederation.

This is not to say that Democrats are born-again virgins on redistricting. Reform of redistricting will work only if every state joins in the illicit act. Governors like to brag that states are the test tubes of democracy. But the reality is that each state acts in its own best interest. Thus we have stasis partly because of redistricting.

Redistricting is legalized bodysnatching. It’s an exercise in partisan self-interest that both parties play and nobody really gives a hoot until 10 years later when it happens all over again. Yet redistricting—the periodic redrawing of Congressional and legislative boundaries—affects the lives and livelihoods of every American every day of every year.

The strengths of a democracy are also its weaknesses. Hogan has taken a tentative step toward reconciling the dark side of redistricting. He’s about to form a commission—yes, another commission—to study ways of performing an exorcism on the intrigue and skullduggery of the census-driven map-making requirement that dates back to the one-man, one-vote Supreme Court ruling of the early 1960s. (The lawsuit was filed as part of a Ph.D. project by the wife of former Baltimore Police Commissioner Donald D. Pomerleau when she was a graduate student in Georgia.)

Ten states have independent or bipartisan commissions to perform the dirty work of shuffling bodies around. Many of them have failed at the task. California, known for extreme swings as cures in its politics, has shifted to non-partisan run-off style elections. The results have been far short of ideal, if not near disaster. (Arizona, for example, adopted the independent commission system of redistricting. Its first run resulted in charges of gross misconduct by Republican Gov. Jan Brewer. The case went all the way to the Supreme Court and the maps were appropriated by the Justice Department for review. In Texas, 11 of 12 Democrats fled to New Mexico to prevent passage of a controversial GOP redistricting plan. There were indictments and the courts eventually had to step in and oversee the process.)

Maryland is somewhere in the middle of the redistricting muddle. Under Maryland’s system, a bipartisan—well, about as bipartisan as it gets in Maryland—commission prepares a plan, submits it to the governor who, in turn, presents the map to the General Assembly. The legislature has 45 days to accept or change the plan before it becomes law. (In 2002, the Maryland Court of Appeals intervened to ease the heavy hand of Gov. Parris Glendening (D) who used reapportionment maps to punish legislators who had disagreed with him.)

Redistricting, and its legislative corollary, reapportionment, have become so perverse that the process now allows legislators to pick their constituents instead of voters selecting their representatives.

The major gripe is that Maryland’s districts lack compactness. That’s true, as far as it goes. But there are several problems with the complaint. First, Congressional redistricting has only one requirement and that is population balance, currently about 720,000 people for each of the nation’s 435 districts. Second, and most deliberate, legislators at every level of government must, in some fashion or another, approve judicial appointments. Thus, the courts are reluctant to intervene in legislative business. And finally, the courts subtly encourage gerrymandering by allowing classic Rube Goldberg boundaries that contort geography to create and protect minority districts. (A federal court has deemed Virginia’s Congressional redistricting plan unconstitutional because it dilutes black power.)

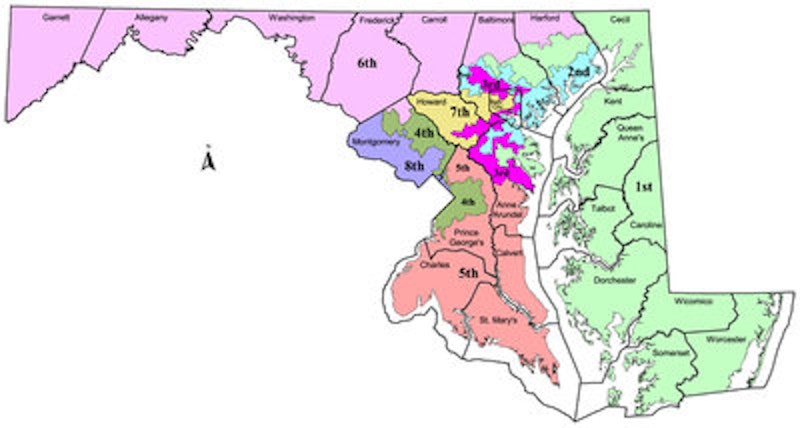

That nifty bit of social engineering, in turn, creates bleached districts. Maryland’s Fourth and Seventh are examples of chocolate districts. And the state’s First District is a vanilla jigsaw that traverses the Chesapeake Bay and connects Cockeysville, in Baltimore County, with Salisbury, on the Eastern Shore, to isolate Maryland’s lone Republican congressman.

Legislative reapportionment (redistricting by another name) is a different matter. There are certain guidelines that must be followed. Compactness is one, and that is to avoid dividing communities and to protect commonality of interests. There have been instances, however, where the pen and the slide rule have been used to punish errant lawmakers and to protect friendly ones. They have been challenged in court. A squiggle on the map here, or an erasure there, or even the shift of a single precinct can often make or break a political career.

Hogan kicked off his first state of the state speech on a downbeat note, to the annoyance of many lawmakers. He postulated the erroneous formulation that people of every age, shape size, color and creed are exiting Maryland for one unhappy reason or another and that half the population would abandon the state if it could.

His fact checkers were wrong. The latest census figures show that Maryland’s population has grown by nine percent. And the numbers from the State Planning Department indicate that there will be more political upheaval when lawmakers gather around the maps again in about seven years. Riot alert! The next census is in 2020. If Hogan runs and wins reelection in 2018, he’ll still be governor when the new maps are drawn in 2022. (And based on current districts, Republicans will probably still control the House of Representatives.)

The population of central Maryland, the core of the Democratic party, is bulging whereas the Republican rural margins are losing (they must be the émigrés Hogan’s talking about). The greatest growth over the past year or so was in Montgomery County (13,000) and in Prince George’s (9000). Baltimore City lost 300 people last year although it had a net gain of 1400 over the past three years.

Redistricting, gerrymandered or not, is important to Maryland. School lunches, housing grants, agricultural subsidies, veterans’ benefits, oil industry write-offs, Medicare and Medicaid, unemployment benefits, defense spending, mortgage interest tax deductions, bank bailouts and the tax code in general—all are among the many lifelines that are directly related to Congressional redistricting.

State budgets are another matter but no less involved in the chicanery of who gets shuffled in the map-making gamesmanship. You send your tax dollars to Annapolis and Washington and in return you get the stuff that makes America tick.

As every political nose-counter knows, Maryland has eight members of Congress—seven Democrats and one Republican. This is a felicitous imbalance that happily benefits a state that is host to a huge federal presence and is aggressively seeking more by pursuing the new FBI headquarters for Prince George’s County. There are 314,200 federal workers in Maryland and the state was fourth highest in the nation with $26.3 billion in federal procurement spending.

The wonder is why—and we know the answer and the campaign promise—the usually laid back Hogan advanced the idea of redistricting reform five years before the next census except that “bipartisan” has a certain sanitized appeal to the purists who find the trench work of politics offensive and, to Republicans, who would like to continue to increase their numbers in elective office.

Hogan may also be misreading the people who elected him as validation of his candidacy instead of rejection of Lt. Gov. Anthony Brown (D). Redistricting may be broke, but it’s not so badly out of shape that it needs screwing up worse as other states have done. But if it has to be accomplished, take it up with Republicans, the folks who messed it up in the first place.