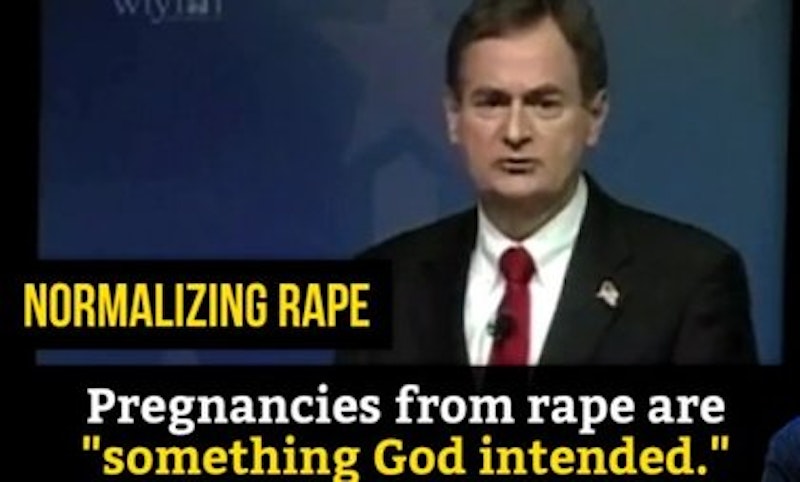

A couple of days ago in a debate, Indiana Republican Senate candidate Richard Mourdock explained his opposition to abortion in the case of rape by saying the following: "I came to realize that life is that gift from God. And, I think, even when life begins in that horrible situation of rape, that it is something that God intended to happen.” This went over poorly. That it went over poorly would, you'd think, surprise nobody. And yet there have been several commentators who do seem startled. Amy Sullivan, for example, argues that liberals are misunderstanding Mourdock.

I was just shocked that anyone was shocked. Lots of Republican politicians oppose rape exceptions. Paul Ryan, for one, opposes abortion in the case of rape. Rarely does anyone bother to offer an explanation for why he holds that position. (Todd Akin famously did earlier this year, and that didn’t go so well for him.) I’m not sure what justifications people had imagined for opposing a rape exception that would be more acceptable than Mourdock’s.

Despite the assertions of many liberal writers I read and otherwise admire, I don’t think that politicians like Mourdock oppose rape exceptions because they hate women or want to control women. I think they’re totally oblivious and insensitive and can’t for a moment place themselves in the shoes of a woman who becomes pregnant from a rape. I think most don’t particularly care that their policy decisions can impact what control a woman does or doesn’t have over her own body. But if Mourdock believes that God creates all life and that to end a life created by God is murder, then all abortion is murder, regardless of the circumstances in which a pregnancy came about.

Kevin Drum has a similar post up, in which he says that Mourdock's beliefs are "extremely conventional," and adds:

What I find occasionally odd is that so many conventional bits of theology like this are so controversial if someone actually mentions them in public. God permits evil. My faith is the only true one. People of other faiths are doomed to spend eternity in Hell. Etc. There's a lot of stuff like this which is either explicit or implied in sects of all kinds, and at an abstract level we all know it. Somehow, though, when someone actually says it, it's like they farted in church.

Mostly what this shows, I think, is that people who don’t respect or care about Christian doctrine or theology are not necessarily well-equipped to comment on it. Which is probably not a news flash or anything, but is worth keeping in mind nonetheless. If you do have an interest in Christian doctrine, I think it's fairly clear that Mourdock's statement is theologically incoherent—and that, contra Sullivan, it expresses a subterranean, but nonetheless definitive, contempt towards, and prejudice against women.

To understand why, you need to go to what’s the theological basis of Mourdock's statement. Mourdock argues that life is a gift from God (which certainly is a theologically conventional statement), and that God intended that life to come into being even in the case of a rape. Christians do not have the right to go against the will of God and take life. This is, essentially, a statement of renunciation. You can hear Mourdock's acquiescence to the will of God echoed in something like Stanley Hauerwas' War and the American Difference.

The political novelty that God brings into the world is a community of those who serve instead of ruling, who suffer instead of inflicting suffering, whose fellowship crosses social lines instead of reinforcing them. The new Christian community in which walls are broken down not by human idealism or democratic legalism but by the work of Christ is not only a vehicle of the gospel or a fruit of the gospel; it is the good news. It is not merely the agent of mission or the constituency of a mission agency. It is the mission. (writer's italics)

What Hauerwas is saying here is that, for a Christian, it is better to suffer than to inflict suffering—better to serve and to acquiesce than to rule and dominate. The Christian witness is that God's will be done, even if that will is the Cross. Hauerwas has been asked about his position on abortion. Here is his response:

I do know some women who have been raped and who have had their children and become remarkable mothers. I am profoundly humbled by their witness.

You may agree or disagree with Hauerwas' response, but I think its difference from Mourdock's is instructive. Specifically, Hauerwas' response is about how he sees the issue as a Christian, and therefore, about what he can learn, and how he can be instructed, by his sisters in Christ. Mourdock's statement, on the other hand, is, in context, a policy proclamation. God intended life, and therefore I, not as a Christian, but as a United States Senator, am going to use the power of the state to make sure that my subjects have babies how and when I tell them to.

Mourdock's position is theologically incoherent, then, not because he is advocating renunciation and acquiescence to the will of God, but because he is advocating renunciation and acquiescence to the will of God for other people, but not for himself. If you are committed to renouncing force even in the extreme case of rape—if you believe humans should not use force to interfere with God's plan—then how can you possibly advocate using force to (for example) kill terrorists? How can you advocate using force to prevent people smoking marijuana? How can you advocate, more pointedly, using force to prevent women from having abortions, since making abortions illegal is, after all, an exercise of state force? If you are really committed to a vision of a Christian community dedicated to renunciation and the Cross, if your theology declares that we must serve God's plan and not rule it, then on what possible grounds can you seek, much less wield, political power?

The answer is that Mourdock believes only certain kind of people should renounce power—people like (for instance) women. He is willing to put other people up on the Cross to fulfill God's plan, as long as he is the one who puts them there. Women are here to suffer; Mourdock is here to rule by telling them how to suffer. This may confuse Drum and Sullivan, but I think most people are able to see that, in siding with the crucifiers, Mourdock is not only cruel and inconsistent, but also un-Christian.

Noah Berlatsky (@hoodedu) blogs at Hooded Utilitarian