It's been a good week for liberals. First Chief Justice John Roberts decided the mandate was a tax. Then Mitt Romney denied it was a tax so he wouldn't have to admit he raised taxes when he passed health care in Massachusetts. Then he said it was a tax because his right wing started flapping and spastically squawking. Then Rupert Murdoch and The Wall Street Journal got pissed off and said Mitt and his campaign were dumb weak losers who were going to blow it if they didn't step up and attack Obama on health care and raising taxes.

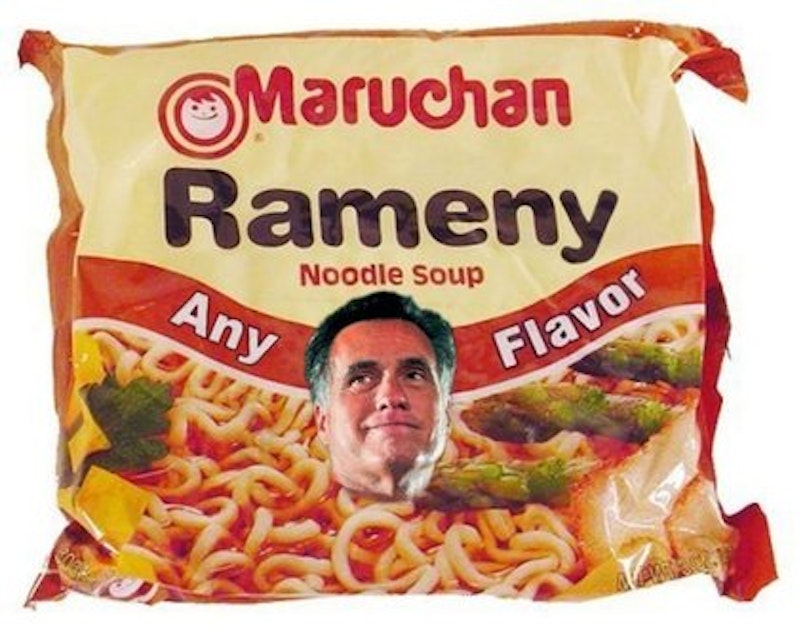

So, as I said, good times. So good that a number of liberal writers have actually taken the opportunity to be magnanimous and sympathize with poor Mitt in his troubles. Jonathan Chait, Jonathan Bernstein, and Josh Marshall all weighed in to say that, while Mitt may be a loser, he is not necessarily stupid or weak. Rather, he agreed that the mandate was a tax because, fundamentally, he doesn't want to talk about health care and he doesn't want to talk about taxes. Health care is to be avoided because he used to support mandates, and voters don't really understand or care about the ACA anyway. He doesn't want to talk about taxes because the Republican position of cutting taxes for the rich is fundamentally unpopular. And most of all, he doesn't want to talk about either of those things because he wants to talk only about the economy, which is the one damn thing that might possibly get him elected if only, please God, the recovery continues to suck or Europe collapses.

Of course, as Bernstein points out, though Romney wants to talk about the economy, he doesn't want to say what he'll do to fix it if he can possibly help it. He writes: "The out-party is almost always best off being as vague as possible, and that's certainly the case when the incumbent party is most vulnerable… Exactly no one is going to vote against Romney because he declines to advocate specific policies, but there's always the risk that embracing one set of policy choices could alienate voters who otherwise might just want to throw the bums out."

Romney's entire strategy—the smartest strategy, since Obama is still personally popular and hasn't lost any wars or stumbled into scandals or mismanaged a natural disaster like his predecessor—is to point out again and again that the economy sucks. Any time spent on anything else is a waste, as far as he's concerned. The Republican base hates the ACA (without having anything to replace it with) and abhors the deficit (without having any plan to reduce it), but if Romney talks about those things, he's not talking about the economy.

Bernstein and like-minded journalists seem pretty much right to me. I think Romney's a repulsive slimeball, but he doesn't appear stupid, and his refusal to put forward policy prescriptions is as calculated as anything else he does. The circumstances are such that it's best for him to obfuscate, so obfuscate he will.

What's interesting to me, however, is that it's not just circumstances that encourage obfuscation. It's our whole system. After all, it's not like Obama is especially forthright about what he's going to do. His drug policy, as just one example, is a marvel of equivocation—he constantly says he's against draconian measures, and then keeps on with the draconian measures. I read political blogs all the time, and I'll be damned if I know one specific policy proposal he's made for his second term. His campaign is mostly about how he's already done great things and how Mitt is a jerk, not about a specific legislative agenda for the next four years.

Of course, any legislative agenda would be purely speculative, since Congress may not cooperate. The President isn't in a position to keep promises anyway, which has to be an important part of why candidates don't want to make them. Romney (and Obama) obfuscate not just because specifics may lose them votes. They obfuscate because they know they can't be called on it.

America’s Founding Fathers, bless their paranoid little anti-tyrannical powdered wigs, separated the legislative power and the executive power, with the presumably unforeseen result that our chief executives aren't accountable for a legislative agenda. In Parliamentary systems, the parties stand for particular programs, and you vote them in to get the program, and vote them out when you want a different one. But in the U.S., you vote for some particular person, not for a series of policies—and as a result, the person has no interest in aligning themselves with the policies. On the contrary, the person wants to get as far away from the policies as possible. Why tie yourself down to unpopular or unworkable ideas that'll only make people hate you? Better to be vague and nice and assure everybody you'll do what they want so you can do what you want when you're in office ("what you want" in this case meaning, of course, "whatever is most likely to get you reelected.")

It's true that Romney's vision for improving America can be pretty much summed up by saying, "America would be better if Mitt Romney were president." The shallow self-regard is somewhat sickening… but it's de rigueur for any presidential candidate. Again, a presidential election is an election of persons, not policies, so anybody running has to figure that they are the best person to lead the country not because of their ideas or policies, but just because they are awesome. Maybe that's why, even by the standards of elected officials worldwide, American presidents seem remarkably narcissistic—even pathologically so in the case of such towering assholes as LBJ, JFK, and Nixon.

That doesn’t mean I'll be voting for Mitt. "Not necessarily any more of a psychopath than a number of former Presidents" is hardly a ringing endorsement, after all. To the minor extent the man's managed to articulate any policies whatsoever (on, say, immigration or Iran) I disagree with them. But most importantly, despite many caveats, I still like Obama personally. Shallow, perhaps… but we're a shallow country. The Founders programmed it that way.

—Read more Noah Berlatsky at hoodedutilitarian.com