I've been following the presidential horse race pretty closely. Mitt Romney said this idiotic thing over there; Barack Obama is down in that poll over there—the news cycle lurches back and forth, and I point my browser and follow it through non-scandals and non-events, not so much because I think it matters as because you've got to have a hobby.

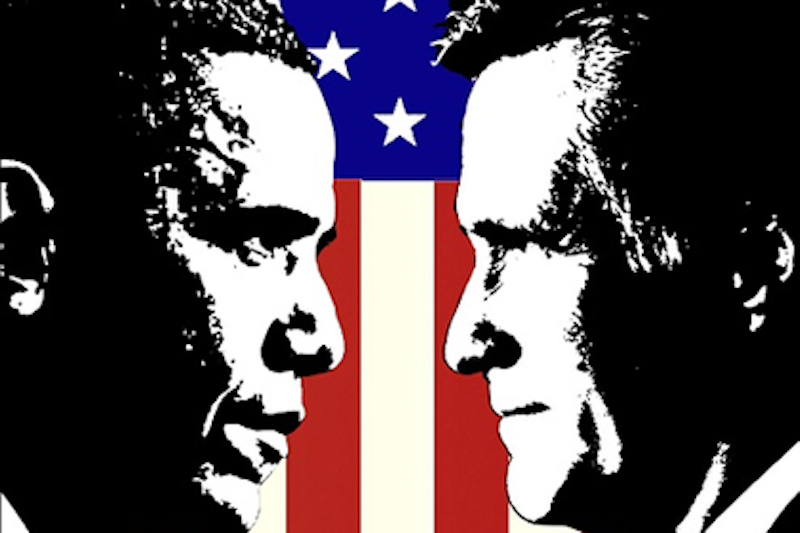

With all that micro churning, though, I think you can sometimes miss the biggest, most obvious points. And in this election, the biggest, most obvious point is that the United States is running an election for president in which the two candidates are an African-American and a Mormon.

Part of the reason this doesn't seem like such a big deal is, of course, because Obama’s been president for nearly a full term already. By the same token, Romney’s been running for President for more than five years. Both men are very familiar figures by this point. That either of them should be president simply doesn't seem that odd.

And yet, that doesn’t mean it’s normal. It was only half a century ago—within the lifetime of many voters—that black people were barred from voting within a substantial part of the union. Less than 25 years ago, in the 1988 Presidential campaign, Jesse Jackson's candidacy was widely regarded as a curiosity. I remember pundits speculating out loud, "What does Jesse want?"—as if even the candidate himself couldn't possibly believe he would actually win the Oval Office. Even four years ago, there were an awful lot of folks who thought that Obama's bid was doomed because of the color of his skin.

And what about Romney? True, Mormons haven’t been subject to the same kind of systematic persecution in the US as blacks. Still, religious affiliation has long been a subterranean, or not so subterranean, issue in Presidential campaigns. Again, not so long ago, Catholic John F. Kennedy famously had to deliver a speech assuring voters that he wouldn’t be under the thumb of the Pope. Mormon candidates have also long faced electoral resistance. When Mitt's father George Romney was running for President in 1967, Gallup found that between 15 percent and 20 percent of the electorate did not want to vote for a Mormon.

I don't mean to suggest that America has somehow attained egalitarian perfection. I just learned that one of my wife's Kentucky relatives, a lovely and generous man in many, many respects, won't vote for Obama solely because the President is black. I very much doubt that he's the only one, either. As for Mormons, figures actually haven't changed all that much in 50 years; 15-20 percent of the electorate still doesn't want to vote for one (though Evangelical resistance to a Mormon candidacy appears to be overstated.)

So yes, racism and prejudice still exist in America, and both very much affect politics, presidential and otherwise. But that makes the current presidential race more remarkable, I think, not less. A central part of the American dream has always been equality—expressed, in a thumbnail version, as the promise that anyone can be President. That promise was betrayed often, and continues to be betrayed right down to the present day, as burgeoning income inequality and the massive cost of campaigning makes it harder for anyone but the wealthy to seek office. But sometimes, in some ways, the promise is also kept. It's worth being thankful for that before heading back into the next news cycle.