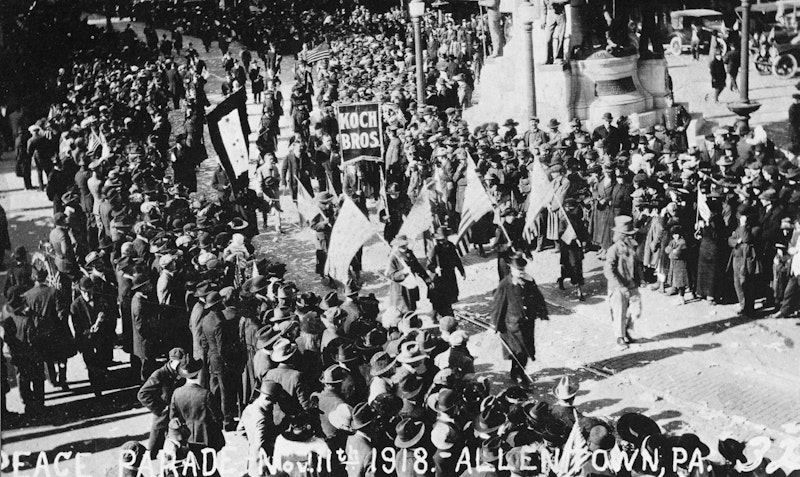

I write this on the 100th anniversary of the end of World War I. It’s Remembrance Day, and just as every year, there are memorials and plastic poppies, red and white. There are speeches, ceremonies and due respect from various media outlets. It’s all the standard Remembrance Day activity, and no more. This surprises me, a little. This Remembrance Day is a special one; this is the centenary of the end of what was once called the Great War. I wonder why more is not being made of it.

There’s a Twitter hashtag marking the date. There are formal ceremonies; Donald Trump’s in Europe to attend one, though going to a cemetery turned out to be too much of an effort for him. Of course, putting Trump in an international setting isn’t likely to promote the cause of peace. This is why Emmanuel Macron didn’t invite him to the first Paris Peace Forum, which follows the Remembrance Day ceremonies, an international summit to encourage multinational cooperation in governance. Oddly, while Macron has linked the Forum to the centenary, the official website of the Forum doesn’t make the connection.

There are reflections, here and there, on the momentous anniversary. But less than I might expect. Has the United States’ bruising midterm election pushed it out of mind? Maybe, but a check of the CBC reveals little beyond a piece by Tony Keene challenging the myth that World War I helped forge a Canadian identity. Otherwise, like the BBC, I find a standard slate of Remembrance Day articles—information on where memorial services are being held, what’s open and what’s closed, a few human-interest pieces. (“Farmer Sprays Poppies On Sheep For Remembrance Day,” reads one headline.) I expected more.

Let’s grant that Remembrance Day has moved well beyond remembering the First World War specifically. But that war is still tremendously important. A quick glance at any history text or even Wikipedia can give any number of reasons: the direct cause of the death of millions, the war was also an indirect cause of the vicious influenza pandemic of 1918 that killed tens of millions more. It led to the rise of communism in Russia, to the birth of the League of Nations and thus the UN, to the spread of modernism in the arts and culture.

One can go on. Frankly, I would’ve expected the difficulty for the media would be in not going on. The centenary was predictable: you knew it was coming and exactly when, meaning there was every opportunity to produce stories, news segments, whole specials about the war. I haven’t noticed much of that. Why not?

The obvious answer: it’s passed out of living memory. There’s nobody now alive who served in any army during World War I. Few people were even alive as children during the war. It’s possible to argue that the war was the real birth of the 20th century, but we’re in the 21st.

I think there may be another reason. World War I doesn’t lend itself well to simple stories. Great poems were written about the waste of lives; but many of the men and women who fought believed in their nation’s cause with all their heart. Other myths say the War was mainly fought in dirty trenches (it wasn’t, outside the western front), that soldiers spent all their time at the front (they didn’t), that generals were hidebound and incompetent (far from universally true, and the way the fighting had evolved by 1918 showed military men struggling to adapt to new technology). There’s a popular image of the war that it takes time to debunk, even aside from the difficulty of establishing what it was about and why so many countries fought for so long.

And the narrative of the causes of the war isn’t simple. Nationalism, militarism, the rise of alliances; the expectation of a short war to settle some open political questions; the relative responsibility of Germany—good luck juggling all this and coming up with a clear story that’s also reasonably faithful to the facts of history. Good luck explaining in a few sentences how most of a continent could sleepwalk into one of the worst wars in history.

It also has to be said that what used to be called the Great War has, with the irony only history can provide, since been overshadowed by an even more deadly war. World War II has everything World War I lacks. Living veterans, to start with. But also a simple story, about democracy and fascism. Clear bad guys, if not clear good guys.

Which is the problem. World War II has a useful set of lessons, but not the ones people think. Everyone imagines that they’ll be able to see the rise of an evil like the Nazis, or of a strongman like Mussolini. But the real lesson of World War II is that people willingly signed up to the dictators’ program, even after the slaughter of World War I. Nobody wants to apply that lesson to the present.

World War I teaches us something more generally applicable, about unintended consequences. However we understand the war, one thing’s clear: nobody expected what happened. The most powerful countries in the world stumbled into mass slaughter because they didn’t know how to de-escalate diplomatic conflicts, and didn’t realize how bad things could get. This is worth bearing in mind.

But something else, too: one of the surprising aspects to the lack of media commemoration of World War I is the fact that film of that war exists. Silent film, yes, and in black and white (though efforts have been made to colorize it). But World War I is something we can see in motion. It’s a part of our world in a way the Boer War or the US Civil War isn’t. It’s vivid, or should be. And yet the power of the movies is not enough to make the war more than a footnote on the 100th anniversary of its end.

Or is it? Events like World War I have many repercussions, unconscious as well as conscious. A new book, Wasteland, by historian W. Scott Poole, argues that the horror film was shaped by the war. Veterans went on to create the horror movie as we know it today, and Poole argues that horror’s iconography of torn-up corpses, dismemberment and trauma, was a reflection of what they lived. We can forget the First World War’s horrors, then, but they’ll linger on. We can’t entirely put history behind us; it remains, in our dreams and visions, to disturb us with echoes we are unable to place and images whose source we have chosen to forget. What will remain, what should remain, is the simplest and truest story of all: war is hell.