As pointed out by John Strausbaugh’s bestseller, City of Sedition, New York City was a hotbed of Confederate sympathizers during the Civil War. This stemmed largely from the profitable pre-war trade between the City and the South in cotton, sugar, and indigo. In a speech at New Rochelle in 1859, New York City Mayor Fernando Wood argued New York’s prosperity depended on southern trade, “the wealth which is now annually accumulated by the people… of New York, out of the labor of slavery: the profit, the luxury, the comforts, the necessity, nay, even the very physical existence depending upon products only to be obtained by the continuance of slave labor and the prosperity of the slave master.”

This was not mere oratory, but a statement of fact. By 1860, according to the U.S. Bureau of the Census, the City’s largest industry was producing garments, with 398 factories employing 26,857 workers to create clothing worth $22,420,769, largely from southern cotton. Sugar refining, the second largest, also depended on Southern cane to refine sugar products worth $19,312,500. These two industries created over a quarter of the city’s gross industrial product. Losing Southern raw materials might devastate the city’s economy.

As Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace note in Gotham, “The city’s key economic actors—the ship owners who hauled cotton, the bankers who accepted slaver property as collateral for loans, the brokers of southern railroad and state bonds, the wholesalers who sent goods south, the editors with large southern subscription basis, the dealers in tobacco, rice, and cotton—all had come to profitable terms with its slave economy.” They feared that secession would mean massive Southern defaults: the non-payment of bills due and owing to New York merchants. Thus, they pressed for conciliation with the South at all costs.

Even in 1860, decades after the United States had abolished the slave trade and had the Navy patrol the seas against slavers, ships launched from New York shipyards and financed by New York investors, though flying foreign flags and manned by foreign crews, carried slaves from Africa to Cuba, where the slave trade was still legal, yielding profits as high as $175,000 for a single voyage.

Moreover, although New York State abolished slavery on July 4, 1827, the Tammany-controlled City government tolerated “blackbirders,” illegal slave importers who operated out of New York. Even U.S. Attorney James Roosevelt refused to prosecute the blackbirders, claiming their activities did not constitute piracy, although Federal law defined it so. The City even tolerated professional bounty hunters searching for runaway slaves under the Fugitive Slave Act, some of whom kidnapped free blacks for sale in the South.

Perhaps all this may explain why Dan Emmett, a minstrel show composer, premiered Dixie, the Southern national anthem, in New York City on April 4, 1859.

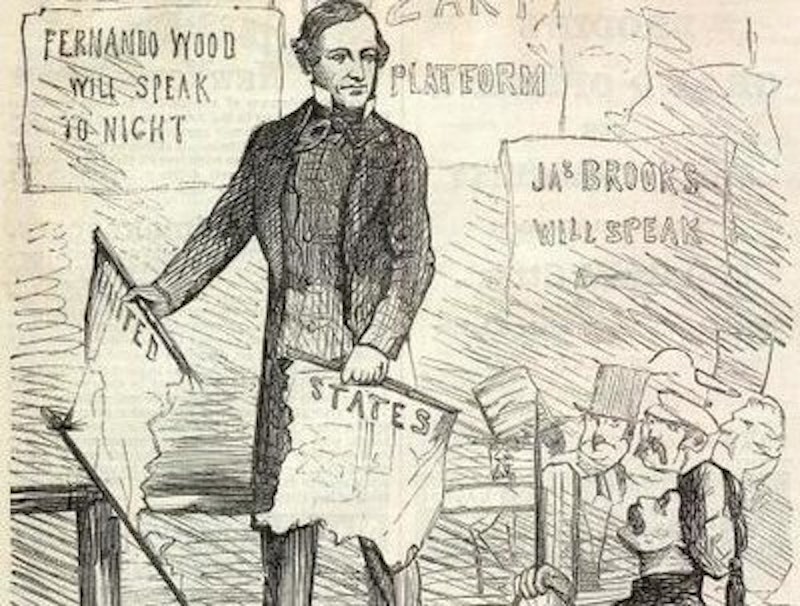

Mayor Wood’s 1861 message to the Board of Aldermen argued, based on the effect of the secession crisis on the City’s trade, that the city fathers should anticipate the Union’s collapse with a policy of neutrality among the northern and Southern states, noting that, “With our aggrieved brethren of the Slave States we have friendly relations and a common sympathy.” He said New York City should strike for independence, “peaceably, if we can; forcibly, if we must.” Finally, the Mayor suggested that New York, as a free city, financed through a nominal tariff on imported goods, could abolish all direct taxation on its citizens. In this speech, Wood may have been the first New York City politician to show that the City provided far more tax revenue to the Federal government than it received in Federal public expenditure.

Theodore Roosevelt noted in his History of the City of New York that the Common Council “received the message enthusiastically, and had it printed and circulated wholesale.” While Wood may have contemplated the common good, as a notorious crook he surely considered the vast possibilities inherent in running one’s own country. According to Luc Sante, the Common Council approved a plan for merging the three islands of Long, Manhattan, and Staten into a new nation, to be called Tri-Insula. Three months later, after the rebels fired on Fort Sumter, the plan was quietly rescinded. The city survived despite over $300 million in defaulted Southern trade debts and over 30,000 suddenly unemployed workers. Within months, the Union’s demands for uniforms, rifles, artillery, and warships restored full employment.

At least three Confederate generals were native New Yorkers, born on the island of Manhattan. Each had developed strong ties through business or marriage with the South. Indeed, each resided in a Southern state at secession. Despite Northern birth and national military service, apparently none of them had more than a mild sentimental affection for the Union, easily overcome by love of the place in which they had come to live.

One had a family name still distinguished in New York City history. Archibald Gracie Jr. was the namesake of Archibald Gracie, a merchant who between 1799 and 1804 built his elegant Federal-style summer home at Horn’s Hook, near what is now 88th St. and East End Ave. The elder Gracie lost his fortune during the Napoleonic Wars, and sold the house in 1823. One hundred nineteen years later, Gracie Mansion became the municipal White House, the official residence of the Mayor of New York.

The future Confederate general was born in New York on December 1, 1832. He was educated in Heidelberg, in the Grand Duchy of Baden, and nominated to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. He graduated 14th in the class of 1854. Two years later, he resigned to go into business with his father, who had moved to Mobile, Alabama.

Gracie joined a local militia company, the Washington Light Infantry. Although Gracie was not only a newcomer but a Yankee, he was elected captain by 1860, which may reflect both professional skill and affability. When Alabama seceded, Gracie’s father adhered to the Union with the rest of the family and returned to New York. Captain Gracie, however, seized the Federal arsenal at Mount Vernon, Alabama, upon orders of Governor Andrew Barry Moore. Parenthetically, father and son remained on warmest personal terms: they simply disagreed over their allegiances.

Gracie’s company was then incorporated into the 3rd Alabama, which marched off to Virginia. On July 12, 1861, Gracie was promoted to Major and assigned to the 11th Alabama. In early 1862, Gracie returned to Mobile to raise the 43rd Alabama. His men elected him colonel. They fought in East Tennessee and Kentucky, where his professional skill and courage won him promotion to Brigadier General. He led his brigade at Chickamauga, where his command sustained 700 casualties in two hours. He also led them at the siege of Knoxville, and at Bean’s Station, where after being shot through the left arm on December 14, 1863, he was back in the field before sundown. During Gracie’s recuperation, he and his brigade were reassigned to General P.G.T. Beauregard’s command in Virginia, where they were on duty in the trenches at Petersburg. On December 2, 1864, Gracie was observing the enemy through a telescope, his head exposed. A Parrott shell exploded nearby, fracturing his neck.

Archibald Gracie Jr. now lies at Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx. Francis O. Ticknor, a now-forgotten Southern man of letters, eulogized him in a now-forgotten poem, “Gracie of Alabama,” which is not worth quoting. The General’s son, Colonel Archibald Gracie of the Seventh New York Regiment, the renowned “Gallant Seventh,” is remembered now largely for having survived the sinking of R.M.S. Titanic and written an extraordinarily detailed book about the disaster, which has not gone out of print.

General William Wirt Allen was born in New York on September 11, 1835. He was named after William Wirt, a former U.S. attorney general and the first third-party presidential candidate, nominated in 1832 by the Anti-Masonic party. Allen was raised in Alabama. A Princeton man, trained as a lawyer, he became a planter. At the outbreak of war, he became a first lieutenant in the Montgomery Mounted Rifles and then won election as a Major in the 1st Alabama Cavalry. In an army of flamboyant and unstable cavalrymen, Allen proved quiet and consistently effective. He became colonel of his regiment after distinguished conduct at Shiloh, and led it through the Confederate invasion of Kentucky (the state had attempted to remain neutral, but different organs of state government had declared for the Union and for the Confederacy, and each nation poured in troops to support its adherents). He was wounded at Perryville and Murfreesboro, losing the use of his right hand.

On February 26, 1864, Allen was promoted Brigadier General and given command of a brigade in the corps of cavalry commanded by Lieutenant General Joseph “Fighting Joe” Wheeler (never wholly unreconstructed, Wheeler was elected a Congressman after the war and commissioned Major General of U.S. Volunteers in the Spanish American War: in the fighting for Kettle and San Juan Hills in Cuba, his command having routed the Spanish, the old man slipped for a moment, crowing, “Look at those damn Yankees run.”). Allen fought well in a losing army, trying to oppose Sherman’s March to the Sea (he was wounded again at the Battle of Waynesboro) and subsequent campaign in the Carolinas. On March 4, 1865, President Davis appointed him Major General. The Senate received the nomination on March 14, referred it to the Committee on Military Affairs on the same day, and adjourned on March 18, 1865. The nomination was never confirmed, as the Confederate States Senate has not sat since.

General Allen was paroled at Charlotte, North Carolina. He returned to his plantation, and unlike many planters was able to scratch out a living in the chaos immediately after the war. He promoted railroad development, was sufficiently connected to be appointed adjutant general of Alabama for several years, and was appointed U.S. Marshal by President Cleveland. General Allen died of heart disease at Sheffield, Alabama on November 24, 1894, and is buried in Birmingham’s Elmwood Cemetery.

The third New York Confederate general, Franklin Gardner, was born on January 29, 1823. His father, Colonel Charles K. Gardner, had retired from the U.S. Army in 1818 after serving as its Adjutant General during the War of 1812. Franklin Gardner was appointed to West Point, where he graduated with U.S. Grant in the class of 1843. He became a career soldier, twice cited for valor during the Mexican War. He also married into the Moutons of Louisiana, a distinguished Creole family, and was so related by marriage to an old friend of mine, Colonel H. Harding Isaacson. This marital alliance may explain why Gardner was appointed Lieutenant Colonel of infantry in the Confederate Army on March 16, 1861. He never bothered to resign from the U.S. Army, which dropped him from his rolls. He fought in Tennessee and Mississippi, commanding a cavalry brigade at Shiloh, and was promoted Brigadier General on April 11, 1862 and Major General on December 13, 1862.

Early in 1863, he was assigned to command the garrison at Port Hudson, Louisiana. He had 6800 troops spread over 4 ½ miles of earthworks. On May 23, 1863, he was besieged by 30,000 Union troops under the command of Major General Nathaniel P. Banks, a former governor of Massachusetts and one of Lincoln’s political generals. On May 27 and again on June 14, 1863, Banks launched all-out assaults on Gardner’s works, resulting in some of the bloodiest fighting of the war up to that time. Gardner’s men were as tough, resilient, and unflinching as their commander, and threw Banks back each time. By July, Gardner’s ammunition was nearly exhausted, his men had slaughtered their horses and mules for food, and even rats were beginning to get scarce.

On July 4, 1863, Vicksburg, Mississippi surrendered to U.S. Grant after an epic siege. Gardner, realizing his situation was hopeless, negotiated surrender. On July 9, 1863, after a siege of 48 days, Banks entered Port Hudson.

Gardner returned home through a prisoner-of-war exchange in August 1864. He spent the rest of the war in Mississippi as part of General Richard Taylor’s command. He then spent the rest of his life as a planter near Vermillionville (now Lafayette), Louisiana, where he died on April 29, 1873. He’s buried in St. John’s Cathedral cemetery in Lafayette. His brother had fought for the Union; his aged father had served as a clerk in the Treasury Department in Washington. General Gardner’s name is commemorated in the Sons of Confederate Veterans, Camp 1421, in Lafayette, which bears his name.

Perhaps the decision of these men to side with the South illuminates the Civil War as a sea change in Americans’ understanding of their relationship to the United States. Once we were New Yorkers and Ohioans and Carolinians and Georgians, with our first loyalties to the states of our birth. The War made us Americans.