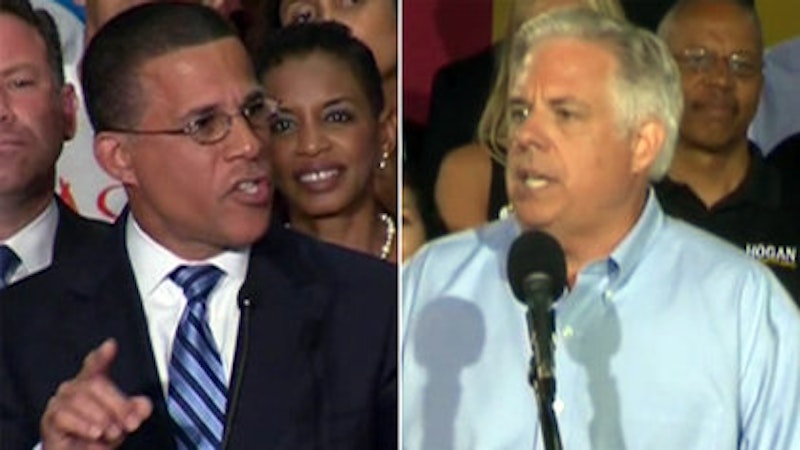

The way the nominees for governor of Maryland are campaigning, you’d think the contest was Martin O’Malley vs. Robert L. Ehrlich Jr. all over again. They might as well be on the ballot in name as well as unnatural godfathers lurking behind the curtain.

To hear Lt. Gov. Anthony Brown (D) tell it, his Republican opponent, Larry Hogan, kicks puppies, scares children and starves families in much the same way his former boss, Ehrlich, did. All the while Hogan wants to give corporations a $300 million tax cut which would pick the pockets of the poor.

And in Hogan’s iteration of the twice-told tale, Brown mimics his higher-up, O’Malley, by putting a gun to peoples’ heads, especially retirees, and taking their money so they can’t by food. Brown, too, helped establish the O’Malley tax policies that are driving retirees out of Maryland to warmer tax-free havens.

For good measure, Hogan would arm every citizen to the teeth, deny women reproductive rights, send children into the world uneducated and pave over the state with superhighways. Brown, in turn, would plunder the transportation fund to build useless rail systems, muck up the state’s health care program and adopt pre-K programs he can’t pay for.

Those are pretty much the ways each candidate presents the other in campaign ads and speeches. Brown warns of Hogan’s “dangerous Republican agenda,” and Hogan counter-charges that Brown’s campaign is “deceitful” and “dishonest.” So the narrative goes: Elect Brown and you get more of the same; elect Hogan and you get a restoration governorship. In either case, it all sounds as if we’ve been there before.

The last time we met these candidates and heard these charges was not this year, or a few days ago, but in 2010 when Ehrlich attempted to recapture the governorship he lost to O’Malley in 2006 after a single term.

Truth to tell, Brown is no more of an O’Malley mini-me than Hogan is an Ehrlich copycat. For one thing, Brown lacks O’Malley’s political skills. And for another, Hogan has none of Ehrlich’s competitive jockstrap mentality.

But more important, the voting public has little or no idea of the arms-length distance between a governor—or any executive, for that matter—and most of the staff that surrounds him on the second floor of the State House.

Hogan was Ehrlich’s appointments secretary. The title can be misleading. The position is not that of a gatekeeper but involves screening and processing the thousands of supplicants, and others under consideration, for the endless list of state jobs and other appointments that a governor dispenses. It is the system of rewards and punishments that help to fertilize politics. The easiest part of the assignment is congratulating people who’ll get jobs; the toughest part is administering anesthesia to those who won’t be appointed.

To say that Hogan influenced education policy, gun control legislation or any other major initiative is a major stretch and attributing too much to the job he had unless Ehrlich, in some casual moment, asked Hogan’s opinion of a certain matter. Hogan may have shortcomings in other areas but not, as far as his state job went, in establishing policy.

Brown is another matter. As the state’s official understudy, the lieutenant governor, unlike the appointments secretary, is an elected official. But—and this is a huge but—the lieutenant governor has only those duties assigned to him by the governor. In other words, the second banana can sit in his opulent netherland office doing crossword puzzles until called upon to perform some ceremonial or lightweight assignment.

Maryland law requires that the governor gives a letter transferring the powers of the governor to the lieutenant governor, if he so chooses, when he will be out of state, otherwise leaving the state technically in limbo if trouble arrives. The letter and transfer are a matter of trust as well as law. There has never been a report, nor has a reporter been known to ask, whether O’Malley has given the full powers of the governor by letter to Brown during his many travels outside of Maryland.

Brown, by his own tacit admission to intimates over the years, had often been frozen out of O’Malley’s inner circle of ministers of influence as is often the case with the supposed second in-command. The protocol stand-off is especially tense at the staff level, where there is a natural protective enmity between the governor’s aides and those of the lieutenant governor.

In the past, for example, Lt. Gov. Melvin Steinberg was completely cut off by Gov. William Donald Schaefer, his staff and friends, following a rupture over tax policy. And Lt. Gov. Sam Bogley was shut out of the councils of government by Gov. Harry R. Hughes when Bogley (and his wife) publicly clashed with Hughes over the administration’s abortion policy.

Brown has had no such known disputes with O’Malley. But it is the nature of the lieutenant governor’s office, re-constituted in 1970 after it was abolished following the Civil War, that creates the unseen barrier. Brown, following the dictate of the law, was given two public assignments—the BRAC (military base realignment) and the healthcare delivery system set-up. The report cards on both are not favorable.

The Brown campaign must be tickled that they’re getting under Hogan’s skin and knocking his campaign off stride. The charges so annoyed Hogan that he called a news conference to denounce Brown and deny the allegations, most of which are untrue (see above). Hogan called Brown’s claims “absolute lies in an effort to slander and defame me.”

Hogan has stated repeatedly that he has no intention of changing the state’s abortion law and favors only a nuanced adjustment that would not affect the substance of Maryland’s strict gun control law. And, “I support pre-K,” Hogan said. “I’m not for taking one penny out of pre-K.”

But here is where Brown and Hogan depart and clash. Brown wants to make pre-K available for every child in the state without having identified the cost or a source of funds. Fiscal analysts in Annapolis put the cost of such an expansion at $138 million a year. Hogan, for his part, has proposed cutting the corporate tax from to six percent from its present 8.25 percent as a way, he says, of creating jobs. Brown says that’s a $300 million giveaway at the expense of Maryland’s families, a figure again set not by Hogan but by fiscal analysts.

Hogan’s campaign is about change, as are most challengers’ campaigns. Brown’s campaign is centered more on an expansion of the existing order, with the centerpiece being the massive broadening of pre-K, one of the current liberal causes to help narrow the achievement gap.

So like it or not, O’Malley and Ehrlich are the brooding backstage presences in this election of a governor. Ehrlich was checkmated by a Democratic General Assembly but nonetheless left behind a record of tax, toll and fee increases that almost matches O’Malley’s dollar-for-dollar.

O’Malley’s record is that of an overachiever who pushed through reams of progressive legislation, including, same-sex marriage, the Dream Act, a tough gun control law and elimination of the death penalty, issues that make liberals’ hearts go pitter-pat as well as burnish his resume as he makes appropriate presidential noises.

The ad campaign does, however, illustrate the difference between attack ads and what are generally viewed as negative advertising. Attacks ads may be nasty but true; negative ads, for the most part, can be both untrue and misleading. But the dirty little secret is that negative ads work. Just ask Hogan.