Now that Democrats control the House of Representatives, the impeachment of President Trump is no longer far-fetched. Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s yet to strongly push the idea, though some are more enthusiastic. Pelosi’s playing it smart: impeachment’s a political process, and you can’t look too eager to override the will of the people. But this raises the question of why impeachment exists at all. Why should Congress get to second-guess the voters, under any circumstances? And what exactly are “high crimes and misdemeanors?”

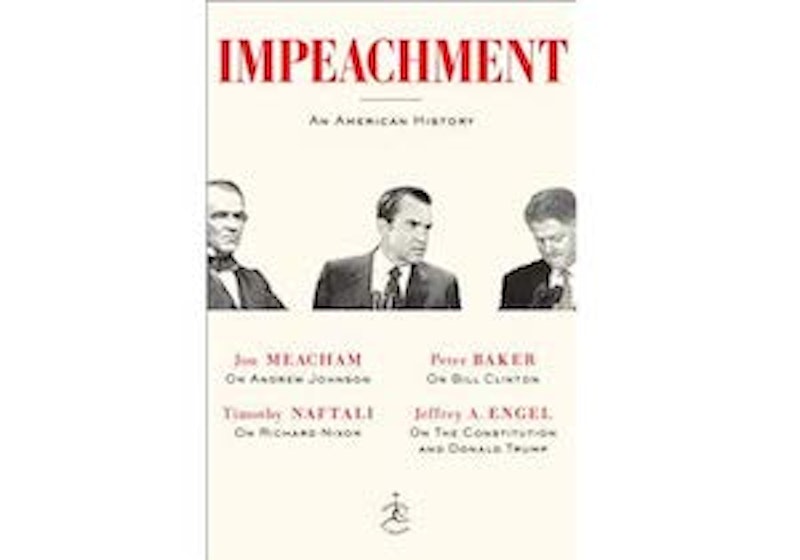

Jeffrey A. Engel provides some answers in a recent book, Impeachment: An American History. It’s a set of four essays by different scholars examining the impeachment process’s history; as well as editing the book, Engel wrote one of the essays, the introduction, and a conclusion. It’s clearly been put together with the intention of being relevant to the current moment, and succeeds admirably.

The first essay proper, by Engel, is a historical overview of the discussions around impeachment during the framing of the Constitution. It’s well-structured and well-written, establishing the background of the Constitutional Convention of 1787, discussing how the presence of George Washington influenced the thinking of the framers, and then describing the back-and-forth that led to impeachment’s formulation as a potential check on the executive.

Ben Franklin gets the best line here. In other systems when a chief executive had “rendered himself obnoxious,” he argued, the result was assassination, which did not lend itself to a fair hearing, even—especially—when it succeeded. Gouverneur Morris countered that impeachment would weaken the executive, but the majority agreed with the fear of North Carolina’s representative William Davie: any president who gained power by cheating would keep on cheating to maintain that power.

Morris ultimately agreed, but demanded that impeachable offenses be very strictly defined. Engel spends much of the latter part of the essay specifying what the framers of the Constitution had in mind by “high crimes and misdemeanors”—broadly, crimes against the state. For the framers, a president had to have a high sense of civic virtue.

Jon Meacham’s essay on Andrew Johnson’s impeachment presents an example of a president lacking that sense, and a Congress who tested the meaning of the Constitution. He gives us a portrait of Johnson’s personality—intemperate, vindictive, at times self-pitying—and then discusses the tensions around Johnson’s attempt to thwart Reconstruction in the South. That led to a motion to impeach Johnson that didn’t make it out of the House Judiciary Committee, and then another motion in 1867 that reached Congress.

Johnson’s sin was general misadministration. Was that grounds for removal from office? The debate was complicated by questions of electoral politics (if impeached, Johnson would be replaced by a hard-line Republican, not the more moderate faction represented by Ulysses Grant) and the House voted down the motion—but early the next year Johnson tried to install a political ally as Secretary of War, and for a third time an impeachment motion was brought forward. This time it passed the House and went to the Senate.

A trial began that lasted for seven weeks, in which arms were twisted and favors called in. Johnson won, barely, and the whole process came to seem purely partisan and therefore illegitimate. The consensus that emerged was that Johnson was incompetent and often vicious, but also that this wasn’t enough to justify impeachment.

Timothy Naftali explains in the next essay, on the near-impeachment of Richard Nixon, how the Johnson impeachment set a number of precedents that gave legislators direction during Watergate. It gave some practical definition to the process—starting impeachment with an investigation by the House Judiciary Committee, for example. But it also gave negative precedents, showing what not to do. The Watergate investigators were determined to avoid the appearance of partisanship.

Though it’s the longest piece in the book, Naftali’s essay suffers from having to fit in the whole sprawl of Watergate. It’s dense, even hard to follow. Naftali has to deal with both the conspiracy and its investigation from a detail-oriented perspective, outlining what Nixon did and when and what investigators knew and when—and then explaining the debate about whether what had been found out rose to the level of impeachment. It’s a tough assignment, with a large and colorless cast of characters.

Naftali does make clear, though, that there was a strong tendency among Nixon’s voting base and even Republican politicians to rationalize away the wrongdoing investigators uncovered. There were real questions about what it would take to override the will of the voters and impeach Nixon: a smoking gun, evidence of a major crime? Or just a pattern of wrongdoing?

As Peter Baker writes about the impeachment proceedings against Bill Clinton, the question of respecting the will of the people didn’t come up in the 1990s. Baker describes a battle for public opinion, which ended up with a widespread perception that Republicans were using a consensual affair to drag a president out of office using a legal technicality. Again, the perception of partisanship was key. The public-relations campaign for impeachment emphasized the political nature of the punishment—and therefore made it politically untenable.

In his conclusion, Engel argues that impeachment’s become debased, too frequently invoked in contemporary politics, if only rhetorically. Impeachment wasn’t raised as a possibility for Nixon or Clinton until their second terms; both 2016 candidates faced the prospect of investigations even before the election. If that sounds idealistic, there’s overall an idealistic tone to this book. Engel argues that the Johnson impeachment suggests, “We should expect senators to at least consider voting across party lines.” This strikes me as a lesson derived from a widely different political situation than the current moment. He argues that Nixon’s case shows that “truth matters,” that when proof comes to light it can undermine partisan support. Again it’s difficult (as Engel himself partially admits) to see this applying in an environment in which the President has consistently urged his supporters to ignore objective truth.

Overall, though, Engel’s book is a clear primer. More details could occasionally be useful; it might’ve helped if one of the essays had described the Judiciary Committee. But it’s smart guide to what one legislator (Democratic congressman Raymond Thornton, in 1974) described as “a safety valve” for the American system of government.

It also has some discussion on the importance of impeachment as an aspect of the Constitution. If the Constitution included impeachment, after all, then however extraordinary a remedy, it also has to be considered a part of the government’s overall structure. The questions about impeachment in the age of Trump may simply reduce to these: If not now, when? If not Trump, who?