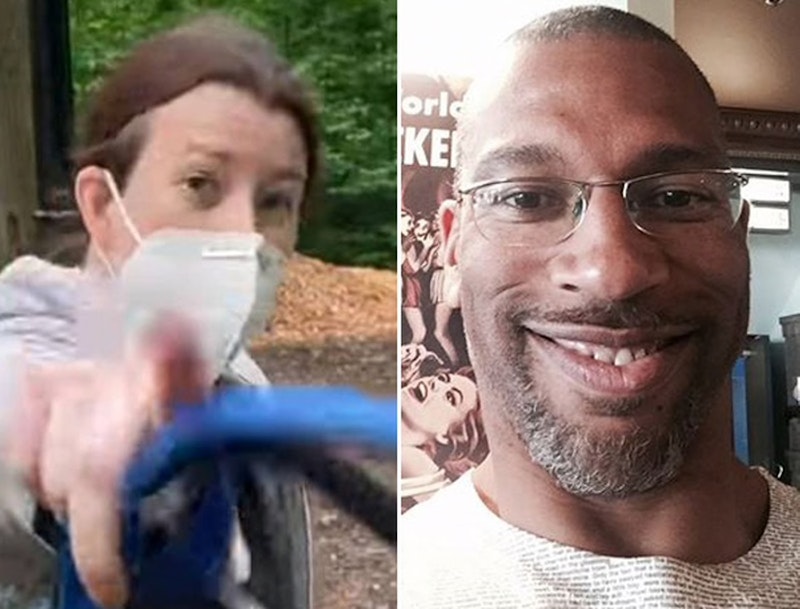

Kyle Smith writes a lot for National Review. His latest offers a perfect example of biased reasoning. It concerns the Central Park dog-walking incident, in which an upper-income white lady threatened a black man who’d been telling her to leash her dog. Her threat: that she’d call the police and make a big deal about his race (“I’m going to tell them there’s an African American man threatening my life”). Smith leaves out that quote in recounting the story, and he hallucinates a threat by the black man to poison the lady’s dog. As a result he can’t understand why everyone has the story so mixed up. He’s sure the man did all the threatening.

Note that the woman herself has said nothing about poison (“made false assumptions about his intentions” is all she can manage in her press statement). Google results indicatethat nobody has except Smith and a commenter at a community news site (the Upper West Side Rag). Both of them think the man was saying he’d poison the dog. Neither of them offers any proof. The eerie thing is that Smith writes as if he delivered tons. The column’s first mention of the word: “So, by his own admission, he threatened to poison her dog.” But if this is the word’s first appearance, how could the column have already quoted some hung-from-his-own-mouth admission by the black man?

It hadn’t. Smith pins all to a post on the man’s Facebook page. In this post, the man set down what he and the lady were saying (or what he remembers them saying) before he started recording her with his camera. “Look, if you’re going to do what you want, I’m going to do what I want, but you’re not going to like it,” the man supposedly said, and then stooped down to get out some dog treats. Smith shakes his head. “He obviously meant her to think he was going to poison her dog to motivate her to leash the animal,” Smith writes. Huh, obviously.

That comment marks poison’s second appearance in the article. In less than 300 words we’ve gone from the poison threat being made “by his own admission” to something distinctly hazier (“obviously meant her to think”). In the very next sentence, the accusation gets blobbier than that: “By his own admission, he said something calculated to frighten her.” The italics are Smith’s; he’s become more urgent as his material wobbles. By the next paragraph he’s back in stride: “when a stranger threatens to poison your dog in Central Park, that is bound to cause consternation.” Apparently the poison claim is one of those things that are steadier when not looked at directly.

I think the man was threatening something much smaller than poison, namely indigestion—people tell me dog owners don’t like strange food getting into their pets. But he was making a threat, and three things stand out. First, the woman remembers being scared by the threat (“I didn’t know what that meant. When you’re alone in a wooded area, that’s absolutely terrifying, right?”), and the media has overlooked this recollection. If the man were white, the episode might be strictly a story about a man making a woman feel insecure in a shared public space. He isn’t, so the story isn’t just that. But that element remains and is ignored by all; it doesn’t factor in somehow. Observe Jezebel, normally a voice for the aggrieved white gal, now dinning in a new cause: “On Monday, a new video surfaced online of a white woman calling the police on a black man for existing in a manner she did not enjoy.”

The third thing is that Jezebel, even Jezebel, has a better line on this affair than Kyle Smith does. “Race does not obviously have anything to do with this story of one New Yorker breaking a minor rule and another New Yorker upping the ante,” Smith writes. The man has blacked out while typing. Words known to everyone else have escaped his brain. Here are the words: “I’m going to tell them there’s an African American man threatening my life.” The black man doesn’t sound like he was intimidated; in fact his Facebook post says he wants more police on hand, so as to deter lawless dog walkers. (Heavy.com provides the quote in a good round-up about the incident.) But what the woman said seems straightforward, and he has described the gist neatly. She tried to “bring death-by-cop down on my head,” the man says.

Smith will have none of it. “Wrong,” he barks. “Phoning the police does not constitute attempted murder.” No proof, of course, but also no italics—this claim is too self-evident. Odd, after the news stories about black citizens getting killed by police. But none of that counts for readers of National Review. The idea doesn’t even have to be argued away. It can be wished away, and for the sake of pretending that the black man, who’s so scary, must get all the blame. As a whole, our country likes to massage the stories it tells itself about race and/or gender; nowadays the massaging is most often in the interest of heightening our sense of liberal indignation. But Kyle Smith just wants to be scared of the black man, and I guess his readers find that comfortable.