Martin Luther King Jr. wasn’t often in the wrong, but one famous quote of his is pretty difficult to live with. I’m sure you’ve seen it recently. “A riot is the language of the unheard,” King said, speaking at Grosse Point High School in 1968. Here it is again, with the usual amount of context: “But it is not enough for me to stand before you tonight and condemn riots. It would be morally irresponsible for me to do that without, at the same time, condemning the contingent, intolerable conditions that exist in our society. These conditions are the things that cause individuals to feel that they have no other alternative than to engage in violent rebellions to get attention. And I must say tonight that a riot is the language of the unheard.”

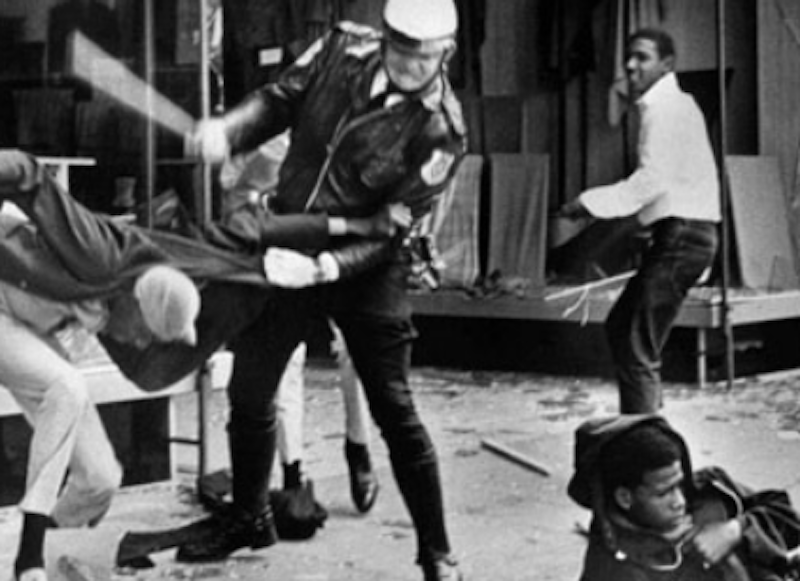

The key, problematic moment here comes when King describes rioting as an attempt to “get attention.” That gives the rioters a motive, and it’s basically a political motive: calling attention to “intolerable conditions.” Then King, by all appearances, congratulates the formerly “unheard” rioters for achieving a “voice” through anti-social, violent behavior. Impressed by his logic, many people actually pride themselves on maintaining a tolerant attitude towards the rioting and looting that has recently broken out in the name of George Floyd.

It’s fair enough for Chris Beck, writing for Splice Today, to characterize our national divide like this: “Conservatives are having none of it, but white liberals have been convinced that looting and burning stores down in your own neighborhood in a race riot is a justifiable reaction to the oppression that black people have always faced in this nation. You’re not supposed to wail about the self-destructiveness of such actions because you can’t understand their emotions.”

Then Beck criticizes the “white liberal” perspective on riots by asking, “But what’s a good liberal to think when the mob incinerates a city bus”?

To do justice to his question, we must return to the words King spoke at Grosse Point High School—but not the ones you’ve already seen 100 times. “Now I wanted to say something about the fact that we have lived over these last two or three summers with agony and we have seen our cities going up in flames,” King begins. He continues: “I would be the first to say that I am still committed to militant, powerful, massive, nonviolence as the most potent weapon in grappling with the problem from a direct action point of view. I'm absolutely convinced that a riot merely intensifies the fears of the white community while relieving the guilt. And I feel that we must always work with an effective, powerful weapon and method that brings about tangible results.”

This precedes his statements about rioting giving unheard people a voice, and it changes the meaning of his point. If “a riot merely intensifies the fears of the white community while relieving the guilt,” then the rioters are speaking on behalf of racist oppression when they haphazardly violate the law. That’s why white supremacist groups have been so eager to serve as agent provocateurs from the very beginning of this crisis. Hate groups will gladly accept short bursts of anarchic violence in exchange for the sustained, systematic oppression of America’s minorities, especially when rioting diverts attention away from legitimate protests against police brutality.

In other words, if rioting is the voice of the unheard, we must accept they’re also a last resort and a bad bargain. When a police force delegitimizes its own authority by conspiring in the brutal subjugation of America’s underclass, some people will take advantage of that lost legitimacy by disregarding the law. These opportunists are not necessarily black, poor, or “liberal.” Their aims are local: destroying something, in anger, or enjoying somebody else’s property. If they were really seeking attention, in a constructive political sense, they’d be taking to the streets with press kits. Classing rioters as “protesters,” or implicitly praising them for their supposed impatience with injustice, is a reckless misunderstanding.

But I don’t want to be wrongly interpreted as saying that rioters have made some kind of political misstep. They’re not a movement. They have no coherent political intentions. Rioting simply demonstrates the power of the police to control mass behavior, including by inciting mobs to acts of senseless violence. It’s a direct result of police brutality and systemic injustice, and it serves the interests of the powerful.

In that sense, it’s wrong to correlate rioting and looting with the particular decisions one police officer made while handling an arrestee. It’s also wrong to hope that imposing a harsh sentence on Derek Chauvin and his accomplices will alter the timeline of unrest. Chauvin, like the people breaking into stores and setting buses on fire, had his own reasons for taking unreasonable action. He’s personally culpable, and so are the other officers who were complicit in Floyd’s death. But in a larger sense, he’s an inevitable result of a police system that protects men and women who terrorize underprivileged Americans. He’s an outlier, but a predictable one. The scariest thing about him is that his private ideas about what he was doing, and why it was justified, make almost no difference at all.

That’s why, above and beyond the error of supposing that rioters are articulating their needs, it’s an error to forgive them on the basis of what they (may) have suffered in the course of their lives. They deserve mercy and forgiveness because they don’t decide the causes or consequences of their actions. Neither do the police officers who violate the inalienable rights of their detainees. People on both the Left and the Right are liable to get these riots wrong. If the rioters were politically aware, you could convert them to nonviolence. If they were the result of lazy policing, you could snuff them out with shows of force. But they’re just an alibi for the status quo. Their voice speaks, loud and clear, on behalf of the communities that don’t care—that don’t even mind—if more people who look like George Floyd are choked to death. The voice of the unheard is, and has always been, for hire, and cheap. That may be the worst part of what it means to be unheard, and to remain that way.