Legislative redistricting is legalized bodysnatching. And in Maryland, there’ll be a lot of it going on during the 90-day session and well beyond into the November election. Incumbent governors love redistricting. It gives them extraordinary power and political clout, especially in an election year and for the two years before it actually happens.

Gov. Martin O’Malley (D) is probably no exception. The redistricting maps are his behind-the-scenes lever to getting his way with the General Assembly and they will be his primal scream to rally the Democratic vote in the September primary election and especially in the November general election if he has, as many anticipate, a tough re-match with former Gov. Robert L. Ehrlich Jr. (R). For Democrats, control of the State House through redistricting is among the most critical and decisive issues of the 2010 election. The career of every Democratic legislator depends on it.

When the last confluence of an election and redistricting occurred under former Gov. Parris Glendening (D), he pronounced himself the “luckiest” governor in America for the convergence because it gave him the unusual vote-pulling power to muscle distasteful programs through the legislature. Glendening kept the redistricting maps on display on an easel in his office to cajole what he wanted by scaring the stuffing out of panicky lawmakers.

Eight, or 10, years later, as the case may be, O’Malley enjoys the same luck. The actual census takes place in a couple of months and the next governor, whoever he or she may be, will redistrict the legislature during the 2012 session of the General Assembly. And for two years after that, many legislators could wind up representing two districts, their old and the new, until the election settles the boundary dispute.

The election-year issue is the fight for control of the State House for the next 10 years. The airborne message: If you like being a legislator, go along with the program or be erased out of a job. A couple of squiggles on the map, or a shift of a block here or there, can change the entire complexion and voter composition of a district.

Redistricting, like political patronage, has evolved from its reform-minded roots into a system of rewards and punishments that takes place largely backstage and out of sight. It works like this: The governor draws the plan, with the help of carefully selected and favored legislators, and submits it to the General Assembly, which can accept or reject the governor’s plan within 30 days or come up with a redrawn map of its own, a highly unlikely prospect. Once a plan is adopted, displaced or disgruntled legislators have only the court of last resort, the Maryland Court of Appeals, which can draw a map of its own, as it did on appeal in 2002.

Every one of the 181 members of the General Assembly as well as Maryland’s eight members of Congress (seven Democrats, one Republican) is subject to redistricting, some with legally protected advantages and others subject to the calculator and the pencil and eraser. There are 47 legislative districts in Maryland, each with one senator and three delegates.

Like much else in the political system, redistricting, with the quiet connivance of the courts, has spun out of rational control. When the courts first ordered redistricting as a reform measure back in the early 1960s, four of the guidelines for creating districts were: proportionality of population, compactness, contiguity and commonality of interests.

Today, legislative and Congressional districts barely resemble that lofty prescription. Districts have been whitened so others could be blackened. Other districts have been legally converted to conservative so others could be liberal, hence the Republican party being reduced to a conservative, regional party in the South. Still others resemble runaway inkblots on the map.

The courts have been ruling in favor of gerrymandering for years as a way of protecting minority populations as well as to pay homage to elected officials who must approve their appointments. Consider how the courts winked at the Texas redistricting plan of former Rep. Tom DeLay (R). It was so gerrymandered that Democrats in the Texas legislature flew out of the state, denying a quorum, rather than face voting on the bastardized plan. And take a look at the Georgia district that was created for former Rep. Cynthia McKinney (D), who was eventually defeated after an embarrassing confrontation on the U.S. Capitol steps. It stretches across Georgia like an elongated strand of linguine—miles long and a millimeter wide.

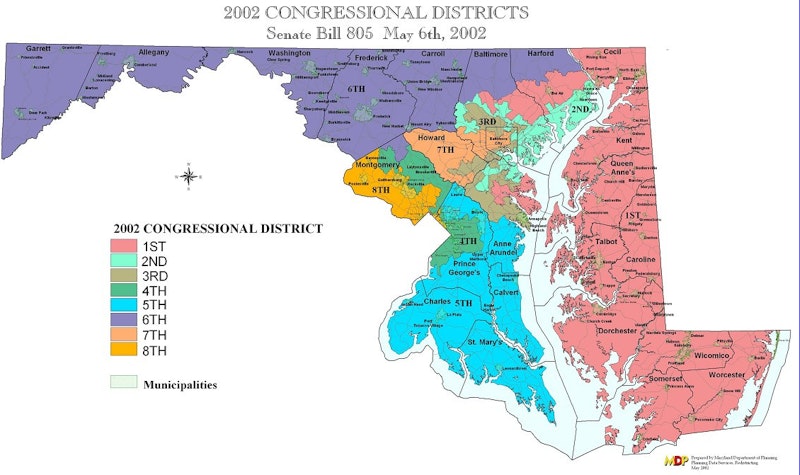

And right here in Maryland, Glendening was in a don’t-get-mad-get-even mode when he redrew the maps in 2002. Maryland’s Third Congressional District was drawn out of spite to punish Sen. Benjamin L. Cardin (D), then a Congressman, who threatened to run for governor against Glendening in 1994. The district is a geographic crazy quilt that stitches Pikesville in with Glen Burnie. The district is almost partitioned into warrens like the Sunnis, the Shiites and the Kurds. Yet the Maryland Court of Appeals allowed the district to stand virtually intact when it reviewed and revised Glendening’s redistricting plan—even as it rearranged the squiggles on the map to carve up Baltimore City. Rep. John P. Sarbanes now represents the Third District.

In an attempt to decapitate Western Maryland’s durable Rep. Roscoe Bartlett, Maryland’s lone Republican on Capitol Hill, Glendening realigned the district into a ribbon that stretches across the top of the state from Garrett County to Harford County. At the same time, Glendening gave Rep. Elijah Cummings (D) territorial rights on what is essentially the city’s Seventh District and he created a totally land-locked Second District for Rep. C. A. Dutch Ruppersberger (D).

And the First Congressional District is another testimony to what must be Glendening’s affection for art of the absurd. The district hop scotches all of the Eastern Shore and parts of Anne Arundel, Baltimore and Harford Counties, raising the question of what Cockeysville, say, has in common with Easton or Cambridge.

At the General Assembly level, Glendening tried another score-settling maneuver against State Sen. Norman Stone (D) who had voted against one of his pet programs. Glendening sliced Stone’s Dundalk area so that it resembled a plate of sushi. It was Stone and his Dundalk cohorts who appealed the vengeful plan to the Court of Appeals and won the ruling to preserve the area intact.

It’s could be that O’Malley is not as mean and vindictive as Glendening, but he is every bit as politically skillful with an added dimension of personal charm. It’s also safe to say that no legislator’s district is sacrosanct from the whims of redistricting or the will of the governor. No man or woman can stake a claim and plant a flag and declare a district as personal property. That’s why O’Malley will pretty much get his way as long as he’s in the State House.