Once, in my 20s, I was talking to a friend, a woman a bit younger than me, and for some unremembered reason I mentioned “selling of indulgences by the Pope.” My friend, who’d gone through 12 years of Catholic school, had never heard of it. I was struck by this gap in her knowledge, presumably abetted by the Church’s reticence to confront its own past.

Around the same time, I was a regular reader of conservative magazines, and setting out on a career in which writing for them was a major aspiration. One such publication was National Review, to which I eventually contributed some articles. My own institutional knowledge had some shortfalls. I’d have thought myself quite familiar with William F. Buckley’s magazine, yet years later, coming across a liberal blogger’s castigation of NR for its onetime support of segregation, I was indignant at this calumny, and then surprised to discover it was true.

I’m currently reading Matthew Continetti’s The Right: The Hundred Year War for American Conservatism, which I recommend even though I’m only about halfway through—in the Nixon years, that is, since Continetti’s narrative begins with Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge. Some have noted that this pushes the story further back than histories that show the conservative movement all-but-immaculately conceived with Buckley’s founding of NR in 1955. However, another valuable history, The Conservative Century, takes a similarly long view.

People throughout the political spectrum may be tempted to overlook unpalatable historical facts, including about the ideas and institutions with which they’re affiliated. At the same time, it’s easy to not want to know much about the “other side,” since that might accord their ideas an undue respect or generate distinctions that complicate a satisfying narrative. In 2012, I heard some progressive friends express fear of Mitt Romney as a right-wing extremist, along with hope that a more moderate Republican might be nominated, such as Ron Paul.

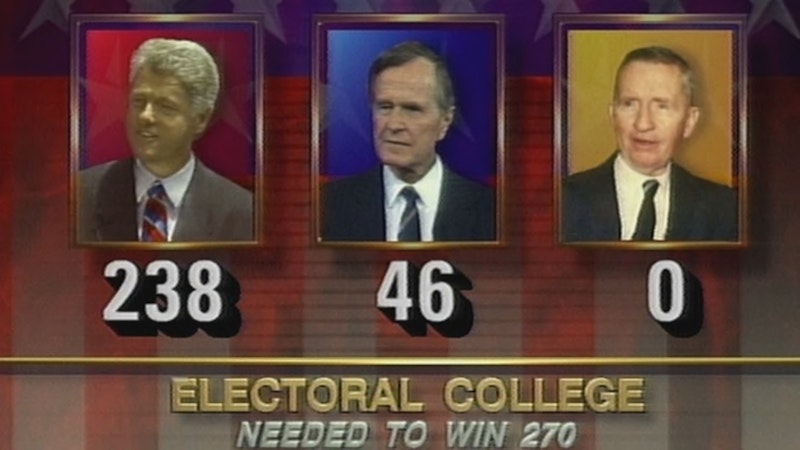

In 1992, I was watching the elections with a Harvard-educated group that, unlike me, was rooting for Bill Clinton and the Democrats. That year, Congressman Bill Green, a Manhattan Republican, narrowly lost re-election. I remember someone in the group expressing awareness that Green was a liberal Republican yet seeing this as a bizarre anomaly. In fairness, it was an anomaly in the context of a Republican Party moving rightward fast; but my interlocutor didn’t know that liberal Republicans had been a powerful force in New York politics for decades.

In the mid-1990s, I interviewed Phyllis Schlafly by phone. I was writing an article for the conservative magazine Insight on the News about an intra-right dispute over a proposed “Conference of the States.” Some conservatives, including at D.C. think tanks, wanted a meeting of state-level officials and activists to coordinate efforts to reduce taxes and regulations. But harder-right, grass-roots types led by Schlafly were having none of it; they thought such a confab would become a runaway Constitutional Convention and scrap American freedoms. Schlafly was friendly and engaging, cheerfully saying. “We’ve beaten them,” as the conference plan was stalling. This minor episode was an early hint that a populist, anti-establishment strain within the right was gaining momentum. That strain had deep roots, but I, with my mix of neoconservative and libertarian views, was only somewhat aware of them.

Continetti describes his own entry into the conservative movement, when in 2003 he walked into the Washington office of the Weekly Standard at 1150 Seventh Street NW, a building that also housed the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) and the Project for a New American Century (PNAC). Looking back, he notes that the Standard and PNAC no longer exist, AEI moved, and the conservative “establishment” they exemplified has been superseded by a more populist right.

The history he unfolds makes clear that the right has always contained varied and discordant elements, and that there’ve always been tensions between different agendas and styles. “Conservatism,” he demonstrates, is not synonymous with “the right,” but rather a subset that’s existed alongside other right-wing tendencies that were more radical or reactionary.

The history recounted in The Right is crucial to know, not least for centrists, liberals and progressives who want to counter today’s right. Such reading would also benefit many Republicans, who may lack a firm grasp of how much the party they belong to has changed, and how much those changes reflect eruptions of attitudes that long were buried beneath the surface, largely overlooked by opinion-makers at conservative magazines and think tanks.

Midge Decter, a neoconservative writer who recently passed away, famously stated that “You have to join the side you’re on.” That’s terrible advice, because it implies an uncritical embrace of ideological allies, regardless of how extreme or misguided they may be, or how they may change in unanticipated directions. My advice is: look at your side, whoever they may be, with a recognition that individuals and institutions sometimes are worse than you think.

—Kenneth Silber is author of In DeWitt’s Footsteps: Seeing History on the Erie Canal and is on Twitter: @kennethsilber