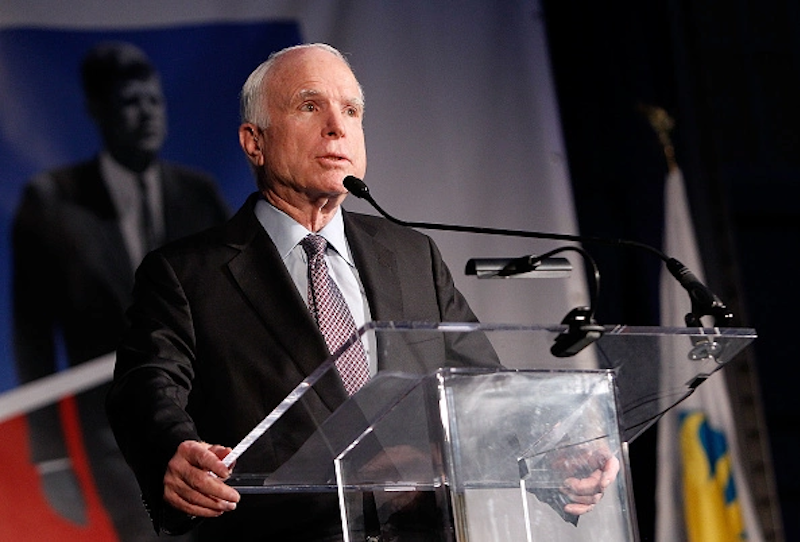

"John McCain is an American hero & one of the bravest fighters I've ever known," Barack Obama tweeted after McCain was diagnosed with brain cancer earlier this week. "Cancer doesn't know what it's up against. Give it hell, John."

Obama's tweet is typical in tone and content to many expressions of support for McCain. Well-wishers often referenced his military service in Vietnam, directly or obliquely, praised his courage, and said he’d fight hard against cancer. McCain, everyone seems to agree, is battling a dangerous enemy, who’ll be defeated by the Senator's great valor and strength of character.

Obama and others are trying to express their admiration for McCain by framing cancer as a war. Still, while their intentions are understandable, the metaphor is misleading. Cancer isn't a battle, and personal qualities like strength, bravery, or honor can do little to halt the disease's progress.

McCain’s brain cancer is called glioblastoma. It’s extremely aggressive. The prognosis for anyone with the disease is bad; most people live only 16 to 18 months after diagnosis. For men over 60, the outlook is even worse.

My father-in-law lived for a little over a year after his diagnosis. He lost function and quality of life rapidly though; for the last few months he was mostly unable to communicate or care for himself. There wasn't much fighting involved in his decline. His doctors gave him chemo, which made him ill, and then he got sicker. The likelihood is that McCain will be dead or incapacitated by this time next year. If he’s lucky, he may beat the odds. But whether he does is largely up to the cancer, his body, and his doctors. It won't be because he's braver, or more willing to fight, than my wife's dad. "As I often talk about in the brain tumor community," Adam P. Newman told me on Twitter "such discourse [of cancer as a battle] also ridiculously implies that those who die are just 'not tough enough.'"

Of course, Obama doesn't mean to say that my father-in-law died because he was insufficiently brave, or didn't fight hard enough. But using martial language to describe cancer does have an effect on how cancer patients are viewed, and on how they view themselves. In Bright-Sided, Barbara Ehrenreich, who contracted breast cancer, writes about the oppressive cult of positivity around the illness. "The words 'patient' and 'victim,' with their aura of self-pity and passivity, have been ruled un-P.C." Ehrenreich says. "Instead, we get verbs: those who are in the midst of their treatments are described as 'battling' or 'fighting'… language suggestive of Katharine Hepburn with her face to the wind." Ehrenreich reported that in some cases, people who have a breast cancer relapse have been expelled from their support groups, since they are no longer "survivors."

Framing cancer as an opportunity for individual effort and bravery is part of the larger American tendency to blame sick people for being ill, or for not trying hard enough to recover. Republican politicians, flailing about trying to justify throwing millions of people off health insurance, often circle around to the idea that people who lack care or are sick have done something wrong. Rep. Warren Davidson of Ohio told a crowd that a man who lacked healthcare should get a better job, suggesting that the man's lack of healthcare was his own fault. Politicians justifying Medicaid cuts claim that people who would be thrown off the rolls don't really need the benefits—they're just shirking. Virtuous people fight off illness without burdening taxpayers. The lazy, the depressed, and the uncourageous aren't really sick. And if by chance they are, they probably deserve it.

It's extremely fortunate that McCain has excellent, government-provided health care. The fact that he does will improve his chances of surviving glioblastoma far more than his bravery or willingness to fight. And if McCain gets very sick very quickly, that's not a sign that he didn't fight hard enough.

Human beings—all human beings who live long enough—eventually get sick and die. That's a hard to face. Language about battles can give people a sense that they are still in control of their own fate, and are not victims. But we shouldn't let the language of empowerment lead us to believe that sick people are actually able to will themselves to health, or that they are responsible for their own sickness. Instead, we need a health care system that helps everybody who needs care—no matter how brave or deserving politicians happen to think they are.