I wrote for the Atlantic online as a freelancer regularly back when James Bennet was editor. It was a very visible gig, though the pay wasn’t great. It ended when I wrote a couple of articles for non-Atlantic venues engaging with and criticizing other pieces published at the magazine. The Atlantic then, and still, publishes articles about the need for free speech and a wide variety of views in the public sphere. But the enthusiasm for a diversity of voices didn't extend to freelance grunts disputing in public the ideas of more illustrious bylines. The opinions of important people are important; everyone else should fall respectfully silent.

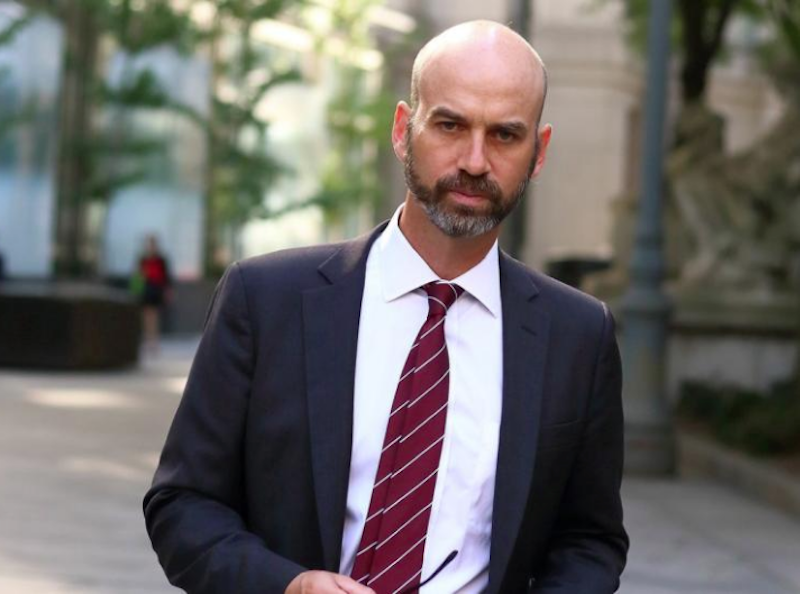

Bennet is exercising that same philosophy at his new opinion page editor job at The New York Times. Last week was a particularly bad one for him. His assistant editor hire Bari Weiss posted a tweet that said that California-born Olympic skater Mari Nagasu was an immigrant. Despite the Times’ restrictive social media policy, she was angry, prompting a slack chat by many NYT staffers that was leaked. Then Bennet announced the hire of tech writer Quinn Norton; he had to fire her five hours later when people on Twitter quickly uncovered evidence she was friends with a Nazi and had repeatedly used homophobic slurs online.

In response, Bennet wrote a 1,500-word memo to staff in which he apologized, and said he was putting procedures in place to make sure that the paper was never again embarrassed in this manner. Joking. He didn't do anything of the kind. He didn't even mention that the Norton hire had happened, and certainly didn't apologize for it. Instead, he reaffirmed his commitment to free speech and diverse viewpoints—unless those diverse viewpoints came from staff and were critical of his management style and editorial choices. He gushed grandiloquent praise for the principle of heterogeneous opinions and made a quick detour into self-pity ("It's particularly hard now because, even as we keep getting attacked form the right, left-wing sites are insistently telling the same story—that we've added conservative voices in a rightward frogmarch—while ignoring inconvenient realities like the powerful new voices from the left that have joined our ranks.") Then, at the conclusion of his earnest brief for free speech, he tells his employees to muzzle themselves.

"I'd like to close with an ask of you: Criticize our work privately to each other as you see fit. Please also let me or our other Opinion colleagues know when you think we have, indeed, put a foot over the line. But please also understand that our folks are acting in good faith. Whether you disagree with some of our many viewpoint or not—surely you will—please understand that your colleagues in Opinion are committed to ideals that matter, to fair play, tolerance, pluralism, the free exchange of ideas and intellectual challenge."

This is phrased as an appeal to Times staff to express their opinions, but it's the opposite. Bennet is telling people not to criticize the paper in public. And he's also carefully delineating the bounds of speech that they’re allowed to express even in private. Staff members have to presume that their colleagues are committed to "fair play, tolerance, pluralism"—even though Ross Douthat, for example, just wrote a column calling for the banning of porn. How is "ban porn" an opinion supporting tolerance or pluralism? Perhaps you could argue that it is—but it’s reasonable to argue that it isn't, too. But Bennet—the boss—is telling staffers they have to assume Douthat is on the side of tolerance in internal discussions, and they shouldn't criticize him in public. When your boss says he has "an ask of you" it's not an ask; it's a command. And if you violate that ask, you're likely to get the boot, as many can testify. Including me.

Bennet's hypocrisy is based on a basic, common misunderstanding about what kind of speech is threatened and why. Bennet believes that he’s fighting for free speech by bravely printing conservative columnists as well as left-wing columnists in the Times. But the truth is that speech isn't primarily policed on the basis of opinion. It's policed on the basis of identity and power.

If you’re Bret Stephens, an affluent white guy with relatives working at the Times, you can spout climate change denial and other nonsense, and editors will nod sagely and pat themselves on the back for being tolerant. If you're a POC working further down the food chain at the Times, you're not supposed to voice any dissent at all when Bari Weiss makes a stupid tweet implying that Asians aren't Americans.

The Times has more regular top line op-ed columnists named "David" than women of color. Bennet's high-profile new hires have both been white (Stephens and Weiss). Charles Blow remains the one regular black op-ed columnist. As I look at the op-ed columnist page now, in fact, there’s not a single female bylined piece among the 10 most recent articles written from the 15th to the 17th of February.

Diversity on the op-ed page for Bennet means men, white people and rich people and especially rich white men who debate hot button issues like, "Should we ban porn?" "Should racists have a seat at the table in immigration debate?" and "Is accusing Woody Allen of child abuse as bad as abusing children?" Everybody else is supposed to shut up.