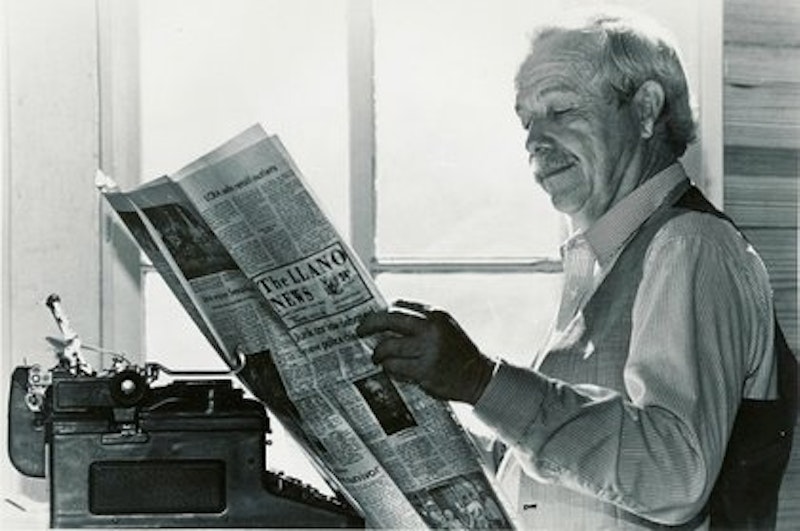

The “Business Day” section of The New York Times on Monday splashed three contrasting media stories on its front page, leaving those readers who actually burrowed through them rather confused, I’d imagine. Harper’s publisher Rick MacArthur—a staunch holdout for paid content whose magazine’s Internet presence is minimal—gets top billing with a picture of him above the fold, and a caption that says he “uses a manual typewriter to correspond with literary friends like Robert A. Caro.” MacArthur, a wealthy man who can afford a self-righteous Custer’s Last Stand, probably knows his 150,000-circulation monthly is in trouble—not long ago, Thomas Frank, the magazine’s best writer, gave up a prime page six column in Harper’s for the foul trenches of Salon, undoubtedly because he wants his work to be read—but it’s a matter of principle for the “stylishly rumpled” 58-year-old.

Next to that article was one celebrating the popular and utterly vile BuzzFeed’s pick-up of a $50 million venture capitalist investment that values the company at “about $850 million, according to a person with knowledge of the deal.” That “person” is probably a BuzzFeed bigshot, but let’s skip comment on the Times’ increasing reliance on anonymous sources. Reporter Mike Isaac did write that BuzzFeed, aside from its listicles and viral videos and cat pictures, has recently “[built] a track record for delivering breaking news and deeply reported articles,” but doesn’t provide even one example.

Yet it was David Carr’s “Media Equation” column that was the meatiest of the three, another lament that print publications are dying. Carr’s eulogy begins by remembering that just a year ago, when Amazon’s Jeff Bezos bought The Washington Post for a fire-sale $250 million, he took it as a sign of optimism for the future of print. (He wasn’t the only one, as the Post’s staff rejoiced. I was skeptical, believing that the pocket change billionaire Bezos laid out was far more likely an experiment for new avenues to increase his business, rather than any love of newspapers.)

That “potential” was misguided, Carr now admits, as he focuses on the spin-offs of print divisions at Gannett, Tribune Co. and E.W. Scripps (following News Corp. and Time Warner), forcing those properties to fend for themselves. Print was “kicked to the curb,” Carr writes, more in resignation than bitterness. (Though he can’t resist a little purple prose: “The recent flurry of divestitures scanned as one of those movies about global warming [I’m surprised the Times hasn’t ordered writers to call it “climate change”] where icebergs calve huge chunks into churning waters.”)

Still, Carr was disingenuous at the beginning of his piece, writing, “The persistent financial demands of Wall Street have trumped the informational needs of Main Street.” It’s bad enough that Carr resorted to the politically-charged cliché of demonizing Wall Street for what displeases him—I’m surprised that bankers haven’t yet been blamed for Gaza and Iraq and Nigeria in the left-wing media—but what he says just isn’t true. “Main Street,” as has been obvious for the past decade, doesn’t want or require the “informational needs” that local and national newspapers provide. The denizens of “Main Street,” which in reality is the entire country, have moved on from legacy media and are happier scrolling Facebook, Twitter, BuzzFeed and countless other avenues to get their fill.

Incredibly, not once in his article does Carr factor in perhaps the key predicament for print publications: young people. I simply don’t understand why older journalists like Carr, who understandably are melancholy about the loss of jobs at newspapers (including friends), refuse to acknowledge that their children—mine, too—never picked up the habit of reading at least one physical newspaper every day, and that the mass of print holdouts are dying off every year.

It’s only at the end of Carr’s article that he offers a neutral response to the rapid changes in his industry. He writes:

“So whose fault is it? No one’s. Nothing is wrong in a fundamental sense: A free-market economy is moving to reallocate capital to its more productive uses, which happens all the time. Ask Kodak. Or Blockbuster. Or the makers of personal computers. Just because the product being manufactured is news in print does not make it sacrosanct or immune to the natural order. It’s a measure of the basic problem that many people haven’t cared or noticed as their hometown newspapers have reduced staffing, days of circulation, delivery and coverage.”

As Carr certainly understands, The Show—days when the Times could, in 1993, spend $1.1 billion on acquiring The Boston Globe (and sold it to Boston Red Sox owner John Henry last year for $70 million) and profit-rich dailies spent lavishly on foreign bureaus and investigative reporting—has closed. Like Carr, I don’t like a media that’s dominated by creepy and secretive companies like Facebook, but men and women of our age don’t count (sometimes I get a start upon realizing that I’m no longer in the desired 18-49 demographic), but we had our shot. As he said, it’s the “natural order.”

—Follow Russ Smith on Twitter: @MUGGER1955