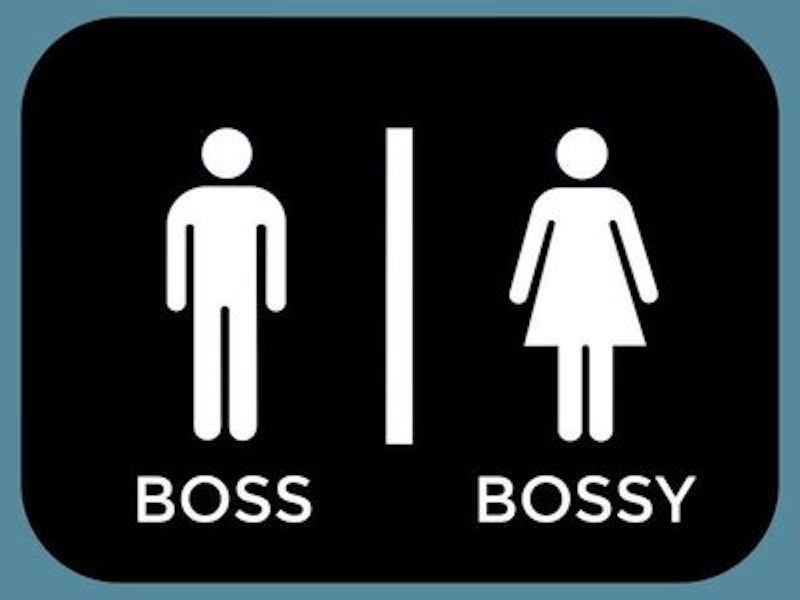

Sheryl Sandberg’s campaign attempting to raise awareness of the obstacles that hinder young girls from developing leadership skills has had many detractors. Many of these critics have focused around the campaign’s focus on language, particularly the word bossy. In support of Sandberg’s efforts, Alice Robb used my own and other linguists’ data to argue that usage of the word bossy is gendered. Nonetheless, the legitimacy of that research has been questioned by Sandberg’s critics. For example, Cathy Young questioned the entire campaign around bossy suggesting that it was designed to address “a fictional problem.”

Young dismisses the language data that others and I have presented supporting the gendered nature of the word itself, stating that “text searches can yield complex and contradictory results.” I partially agree with that statement. Yes, text searches can lead to contradictory findings, although, as I’ll explain below, in this case, the contradiction is largely a product of Young’s use of unprincipled methods for studying language that make it appear that there is more contradiction in the data than there is. It’s also true that interpreting the results of textual analyses can be a complex endeavor, yet, in this case, the complexity of the findings does not prevent us from making cogent claims about differential treatment of men and women.

Young contradicts our findings by picking several different phrases to search through Google’s search engine and stating that these show that bossy was used more for men and boys than for women and girls, which would contradict my and other linguists’ findings. I replicated Young’s results and present them in the table below.

Young’s analysis would suggest that actually bossy is used slightly more frequently for men and boys than for women and girls, which is the opposite of what researchers, including myself, have reported. However, any good researcher would ask Young the following question: “Why have you restricted the analysis to these particular phrases?” In effect, Young’s analysis appears to be nothing more than an exercise in hunting down the data that would fit her preconceived conclusion. If we expand her data set to include similar but absent phrases we find a strikingly different result as in the table below shows my expansion on Young’s Google search technique.

Expanding on Young’s analysis, I arrive at the finding that bossy is used for women and girls about one and a half times as frequently as it is for men and boys. At this point, it would be understandable if readers thought, “Well you could always add more and different phrases and perhaps arrive at a new conclusion, so this whole process of text analysis is fraught with problems.” That conclusion would be correct if all attempts at text analysis were like Young’s. However, the techniques used by linguists to study this topic are quite different from what Young did. They are designed to address the problems related to researchers selecting the data that confirms their pre-conceived conclusion (or “cherry-picking” as we call it).

The first technique is to rely on more flexible approaches to searching. For example, Alon Lischinsky (Lecturer in Media and Culture Studies at Oxford Brookes University) used Google books Ngram viewer to show that the ten nouns that occur most frequently after the word bossy include four referring to women (woman, women, wife, mother) and no nouns referring to men, as you can see in the graph below (or by clicking here). This approach compares a seemingly infinite number of different phrases including “bossy men,” “bossy women,” “bossy girls,” and “bossy refrigerators” to arrive at the most frequent of them all and avoids the selectiveness of only comparing two as Young did.

(Click here to enlarge above graph)

Another possible approach is to use a concept known as collocation. This asks the somewhat complex question of which words tend to occur around bossy (x number of spaces to the left or to the right) at a rate that’s higher than these same words occur elsewhere? I employed this approach using the Corpus of Global Web-based English. The words that collocate with bossy in this corpus are presented in the table below ranked according to a statistic that calculates the word’s tendency to occur in the vicinity of bossy (that is the mutual information score). They include the female-gendered words sister, she, and her but no male-gendered words. This captures and aggregates across an even greater number of possible phrases than the previous one because it allows for such diversity in phrases as these two, which occurred in the data:

- … older sister can be quite bossy. She’s the middle child. I’m…

- …the younger sister with a bossy older sister who I adore…

The diversity of phrases captured through collocation then is much greater than in the approach used by Young.

Finally, the most flexible approach is one that is much more labor intensive. It involves gathering a random sample of instances of bossy and then simply reading through all of them to determine who is being labelled bossy. This is what I did in a recent blog post. Because of the amount of time involved, I looked at far fewer examples than any of the approaches I’ve discussed, but I also was able to classify instances that the above would’ve missed. The graph below illustrates what I found, that bossy was applied to women and girls three times more frequently than it was to men and boys. Because this technique relies on random sampling from a corpus of language and interpreting all possible uses of bossy, it’s also a more principled approach than Young’s.

(Click here to enlarge above graph)

All three of these approaches provide the flexibility necessary to search across different contexts of usage to arrive at a principled analysis, and they all point to the same conclusion: bossy is used more frequently to describe women and girls than men and boys. As a result, the contradictions in the data that Young alludes, while curious in that they suggest gender differences that buck the trend for particular phrases, they are nonetheless a relic of her own flawed attempts at textual research and do not generalize to the broader picture of the way bossy is used. When we avoid cherry-picking the data, the findings are clear, and they support Sandberg’s and others’ contentions that bossy is gendered.

Another issue Young and others have raised is that how the word is used is more complex than can be revealed through textual analysis. In particular, Young claims that two of the examples that I provide in my blog post are “positive” or “neutral” and thus cannot possibly point to a problem for women and girls. For example, I found this use of bossy in my data: “It seems like we [men] hate it when you’re [women are] bossy, but really, we only hate it when you boss us around.” The writer goes on to describe women’s bossiness as “totally hot” when directed at others. There is complexity here, namely what to do about a use of bossy that is framed by the original writer in a partially complimentary fashion. In other words, women’s bossiness when directed at others is apparently “totally hot”, which could be a desirable thing. However, this confuses the issue. The claims that linguists such as myself are making is that the word is gendered, in other words that it is applied disproportionately to one gender (in this case, women and girls), not that it is universally used in a fashion that is intended to be disparaging.

However, this raises the question of whether this comment ostensibly intended as a compliment is still itself part of a larger problem. To take another common example, we might find that women’s physical appearance is more likely to be commented on than men’s. Although these comments may very frequently be intended as positive or complimentary, they still point to different societal treatment for men and women. Therefore, compliments, as good as they make some people feel, may reflect problematic expectations about how women should dress or look or problematic prioritization of women’s physical appearance over their other traits. Likewise, if people comment on women’s “bossiness” more than men’s, even if it is sometimes done in an ostensibly positive fashion, it still suggests the presence of different treatment for different groups of people.

Since feminism aims to bring about equality in the political, economic, and social treatment of men and women, from the point of view of feminists such as myself, the gendered nature of the term’s use in society is an indication of a problem. Of course, the frequency counts and statistics say I’ve presented here say nothing about the moral goodness or political expediency of bossy or any other gendered language; they only show the observed tendency of the term to be used more frequently for women and girls than for men and boys.

Whether or not we choose to think the gendered usage of bossy is a problem and the amount of attention we feel it deserves are two questions that cannot be directly addressed by this data or really any empirical observation. We have to turn to our political or moral beliefs. In this case, feminism and anti-sexism provide the assumptions that many people, including myself, use to interpret this as a problem. Specifically, because feminism stresses equal treatment of men and women, I interpret the different treatment revealed in the gendered usage of bossy as a problem. You could, of course, approach the data making sexist assumptions about the world, such as the idea that women are inherently more bossy than men or the belief that women should have less of a right to be bossy than men. There are countless issues with such assumptions, not the least of which is that they are sexist.

Defining the nature and scope of the problem as well as what should be done about it are of course other issues. It has been repeatedly pointed out that banning the word itself is unlikely to be a good solution. Robin Lakoff (Professor of Linguistics at UC Berkeley), for example, notes that even if somehow we were successful at banning bossy, there are numerous words like aggressive just waiting to fill the functional void that bossy would vacate. Nonetheless, it is valuable to think about the language we use as it reflects the societal and political norms that govern our behavior and structure our society. The gendered usage of bossy thus is not itself the problem but rather a symptom of society’s differential treatment of women, a problem worth solving.

You can read more from Nic Subtirelu at his blog linguistic pulse.