At the least, give James Wolcott credit for this: he was first out of the gate in providing a list of all the books coming out to cash in on the 50th anniversary of John F. Kennedy’s assassination. Granted, the pop culture critic was working within Vanity Fair’s now-quaint leadtime for its November issue, but like a music reviewer who cuts on line and offers a retrospective of the year’s releases in early December, it’s likely Wolcott’s laundry list/memoir is the one JFK enthusiasts will read. The oncoming rush of similar stories—the “Where I Was When Kennedy Was Shot” that the likes of E.J. Dionne, Maureen Dowd, Al Hunt and Tom Brokaw have had in the can for a year—will appear in a blur around mid-November.

Yet it’s a surprisingly tame essay from Wolcott, who even in his early dotage still possesses the artful nastiness that’s long disappeared from his peers’ arsenal. I guess it’s because Wolcott was a genuine JFK fan, and just as the BBC satire That Was the Week That Was suspended its usual format the week Kennedy was killed, some historical events are sacred even for a delightful crank like Wolcott. How else to explain the following gooey reminiscence? He writes: “For kids my age, it was like losing a father, a father who had all our motley fates in his hands. (During the Cuban missile crisis, of 1962, a lot of us grade-schoolers thought we might be goners, our Twilight Zone atomic nightmares about to come true.)”

I’m a few years younger than Wolcott, but of course remember the day well, and yet I find his definitive, speaking-for-a-generation tone both offensive and wrong. One, as shocking as Kennedy’s murder was, it wasn’t “like losing a father,” and to suggest so is an affront to all the children who actually did lose their own father at a tender age. Two, in comparison to the national mayhem later in the 1960s—riots, demonstrations, Vietnam body bags, the shootings of Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy, college students seizing buildings—that day in ’63, at the time, seemed like an aberration. Sure, it was an almost week-long continuous newsreel on TV, but for “grade-schoolers” it was soon back to life as usual, with Christmas coming up and then a few months later the Beatles-led British Invasion turning the culture on its head. Despite Kennedy’s youth (for a president), wit, good looks, stunning wife, money and “charisma,” he was born in 1917, and very much a man of the World War II era. Had he lived, it’s likely he’d have had almost no comprehension of the emerging Pepsi Generation—until, like civil rights, it was explained to him.

It’s a mundane Wolcott effort. After the exhaustive list of all the books that will be featured on Amazon and at Barnes & Noble (at least the franchises that can still pay their creditors), Wolcott writes: “It’s too much and it’s not enough. It will never be enough. Readers will never be sated, because too many hidden dimensions and murky links remain, an atticful of unanswered (and unanswerable) questions, hints of the possible future of which we were robbed. History left us hanging.”

That may be true for people over the age of 55—I’m not immune, as I just bought Robert Dallek’s Camelot Court: Inside the Kennedy White House—but I’m betting that most of these books bomb, mostly because for most Americans those tumultuous days in 1963 are ancient history. Kennedy’s assassination might as well have occurred in the 19th century. Save for ascending and budding historians, where’s the audience for yet another encore of Camelot?

Lee Harvey Oswald? Who dat? Same with Jack Ruby, Jim Garrison, Barry Goldwater, “the best and the brightest,” and even LBJ.

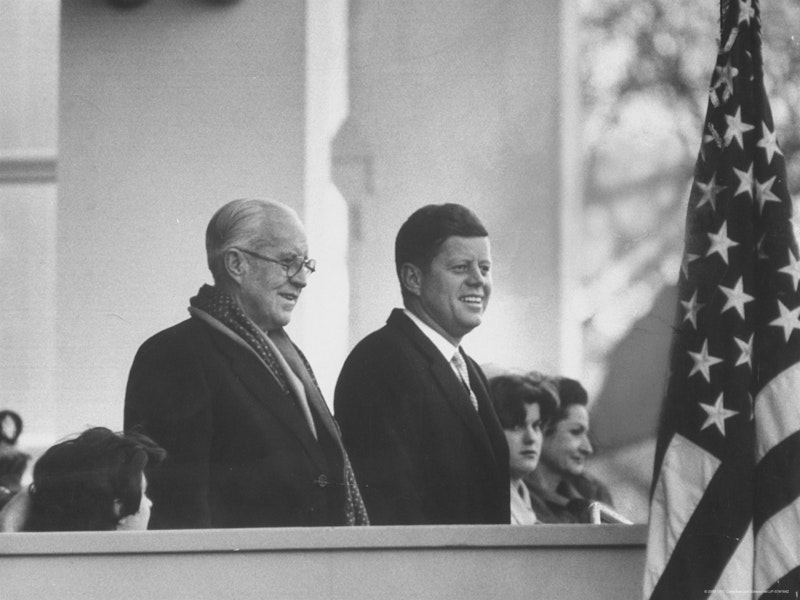

Wolcott reminds readers that Kennedy was the country’s first “Pop president,” a man who took full advantage of television. No shit. And he cites—and won’t be alone—Norman Mailer’s triumphant 1960 Esquire article, “Superman Comes to the Supermarket,” still a Top Tenner of the “new journalism” (a phrase that’s even more antiquated than the flickering interest in the vast Kennedy family.) Oh, and to keep things current, Wolcott throws in a reference to Mad Men and depicts Oswald as a “runty version of Ryan Gosling” who wasn’t worthy of such ignominy.

Strident in his hatred of the current GOP/Tea Party/Religious Right, Wolcott concludes: “The scary thing lurking behind all of these assassination-haunted books is the awareness that we have immensely more gun nuts running around today than we did in 1963, and they are toting a lot more fire-power. Each ramp-up of rabid animus raises the odds of another Dallas, and there’s a lot more of that frothing around, too.”

I doubt Wolcott was thinking of Sen. Rand Paul when he wrote that paragraph.

—Follow Russ Smith on Twitter: @MUGGER1955